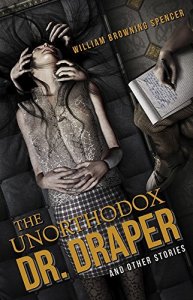

Paul Di Filippo reviews William Browning Spencer

The Unorthodox Dr. Draper and Other Stories, by William Browning Spencer (Subterranean 978-1596068315, $40, 288pp, hardcover) July 31, 2017

The career of William Browning Spencer stretches back at least as far as 1990, when his first novel, Maybe I’ll Call Anna, appeared. A wild-eyed talent not easily categorizable–think David Bunch, Neal Barrett, Barrington Bayley, or Howard Waldrop–Spencer has had a notoriously hard time producing fiction and getting it published–and, consequently, a hard time also in staying afloat in this knife-edged world where capitalism rules with an iron fist. In those nearly three decades since Anna, he had brought us only an additional four books–according to my count from his ISFDB entry. But each one has been unique and something to cherish. I began reviewing him over twenty years ago, and have faithfully awaited each rare manifestation of a new Spencer book. And this month I and Spencer’s other fans are again rewarded–thanks to the loyal sponsorship of Bill Schafer and Subterranean–with a new collection. This year is therefore automatically an annus mirabilis.

The career of William Browning Spencer stretches back at least as far as 1990, when his first novel, Maybe I’ll Call Anna, appeared. A wild-eyed talent not easily categorizable–think David Bunch, Neal Barrett, Barrington Bayley, or Howard Waldrop–Spencer has had a notoriously hard time producing fiction and getting it published–and, consequently, a hard time also in staying afloat in this knife-edged world where capitalism rules with an iron fist. In those nearly three decades since Anna, he had brought us only an additional four books–according to my count from his ISFDB entry. But each one has been unique and something to cherish. I began reviewing him over twenty years ago, and have faithfully awaited each rare manifestation of a new Spencer book. And this month I and Spencer’s other fans are again rewarded–thanks to the loyal sponsorship of Bill Schafer and Subterranean–with a new collection. This year is therefore automatically an annus mirabilis.

Spencer’s deadpan, droll, caustic introduction sets the tone for the rest of the book. Despite the variegated bizarro (yet utterly empathizable) characters and exotic settings of these stories, they share similar themes: betrayal of friends, family, self; the death of dreams and ambitions; heartbreak; the futility of artistic striving with its inherent material limits. But despite these sobering topics and vectors–Spencer himself notes: “Looking over these stories, I see that they are pretty dark.”–the overall effect of this collection is to reassure the reader that bits of glory and consolation and pride can be rescued from the wreckage, if only a person hews to their ideals and a sense of what is right, and has the courage to perform.

The volume opens with “How the Gods Bargain,” a Lovecraftian Mythos story which casually informs us that Miskatonic University has a “sister school, Legrasse.” But far from other less sophisticated pastiches, the tale has a bright naturalistic surface which very effectively highlights the eldritch aspects. Three adults, friends since high-school, have a dire reunion in a occult General Store. Only one emerges.

Sam Silvers, the protagonist of “Penguins of the Apocalypse” (a title worthy of Gary Larson’s Farside strip) is typical of Spencer’s down-and-out guys. Living above a bar where he drinks too much, this deadbeat dad nonetheless tries to do good by his son Danny. But when Sam has the misfortune to meet a fellow named Derrick Thorn, he discovers that a hasty, casual wish he made has come true. In another era, this would have been a primo episode of The Twilight Zone. Can Sam reverse his misjudgment and best Thorn? Maybe, if he is willing to make a sacrifice. Be sure to enjoy Thorn’s brilliantly fractured speech patterns.

Wally Bennett, from “Come Lurk With Me and Be My Love,” also meets an odd person: an alluring woman named Flower. But she seems to belong to a cult whose bible is a book titled Of Pandas and People. Can Wally woo her? Should he woo her? And what of the shotgun marriage proposed by her enormous inhuman father? “He looked like Walt Whitman, Wally thought, if that great poet had weighed an additional three hundred pounds, had a thick slab of a brow that kept his eyes in constant shadow and a voluminous beard, mottled with gray-green moss or lichen.”

Anyone desirous of following the writer’s life should first read “The Tenth Muse.” Our hero, Marshall Harrison, is a struggling hack locked into producing a series of mystery novels he knows are below his talents. His dead father had a best-selling book of poetry whose success drove him to suicide. And Marshall’s new journalism assignment is to interview an old family friend named Morton Sky, whose one bestseller left him unable to write anything else. But these tawdry circumstances are all revealed to have occult underpinnings, which could prove fatal for all.

Stolen brutally from his family, the child named Stone becomes a vassal of the Librarian, in the aptly named “Stone and the Librarian.” The leader of “Knowledge Base #29” proves to be a scavenger from the far future. And the tortures he puts his charges through–reading Moby Dick and Remembrance of Things Past–are utterly inhuman! Needless to say, black humor here abounds.

The narration in “The Indelible Dark” shifts back and forth between two milieus. First we see a post-Armageddon future in which a boy named Mark Cory must battle against mutants called Lethe’s Children. Then we return to the present to witness the shabby plight of another writer, very much a Kilgore Trout avatar. But when the writer experiences a wound in his belly that does not bleed, both scenarios go rapidly off the rails.

Pure virtuoso comedic steampunk, “The Dappled Thing” charts the jungle adventures of Sir Bertram Rudge and his miraculous vessel, Her Glory of Empire, as Rudge and companions search for the missing woman named Lavinia. But only upon a successful return to England do the ultimate consequences of the wild adventure appear.

Brad and Meta, a happy young couple, are driving along a deserted highway in “Usurped.” Suddenly, an attack by wasps sends their car careening off the road. When Brad awakes in a hospital, he and Meta have divergent memories. Later, a strange fellow appears and offers an explanation. Should Brad pursue his investigations, or leave well enough alone? We might suspect that plunging deeper into the mystery will be fraught, but the ending that Spencer offers is unforeseeable.

Lastly, the title story finds the loony psychotherapist Dr. Draper at a loss about how to deal with Rachel, his newest recalcitrant and blocked patient. He hires a detective, Milton Caine, to dig into Rachel’s past. What they find–the tip of the iceberg is that Rachel’s alternate personalities take on very potent forms–leads them down a Jungian maelstrom.

And as lagniappe, we get an original poem, whose title says it all: “The Love Song of A. Alhazred Azatoth.”

The writers I cited at the head of this piece share with Spencer the quality of being one-of-a-kind creators functioning out of the mainstream. But Spencer’s elegant prose, off-kilter conceits, and mordant view of existence also summon up comparisons to folks with a larger audience, such as Kelly Link, Jeffrey Ford, Jonathan Carroll, and Robert Aickman. It is an illustrious company he belongs to, and he deserves as much success as any of his fellows. With luck, this book takes him one step closer to that reward.