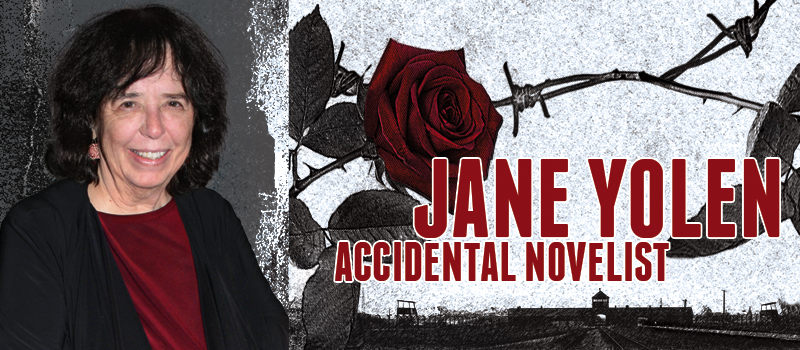

Jane Yolen: Accidental Novelist

Jane Hyatt Yolen was born February 11, 1939 in New York City. She received a BA from Smith College in 1960 and a master’s in education from the University of Massachusetts in 1978. She married David W. Stemple in 1962 (he died in 2006), and has a daughter, two sons, and six grandchildren. She has collaborated on works with all three of her children, fantasy most extensively with Adam Stemple.

During the ’60s, she worked in New York at various magazines and publishers, holding editorial positions at Gold Medal Books, Routledge Books, and Alfred A. Knopf Juvenile Books. From 1990-96 she ran her own YA imprint, Jane Yolen Books, at Harcourt Brace.

Yolen is the author or editor of over 350 books, with most of her writing for children or young adults, though she has also written adult novels, poetry, and non-fiction. Her first book, non-fiction Pirates in Petticoats, appeared in 1963 (and was revised and updated as Sea Queens in 2013), followed by a children’s picture book, See This Little Line (1963). Her first novel was the co-authored realistic fiction Trust A City Kid (1966). The short middle grade fantasy novel The Magic Three of Solatia (1974) mingled children’s and adult fantasy.

Among her many works of genre interest, standouts include time-travel Holocaust novel The Devil’s Arithmetic (1988) and ‘‘Sleeping Beauty’’ Holocaust tale Briar Rose (1992); a third Holocaust book, A Shudder Between the Hills, inspired by ‘‘Hansel and Gretel’’, is forthcoming in 2018. Her adult fantasy Great Alta series began in 1988 with Sister Light, Sister Dark and continued with White Jenna (1989) and The One-Armed Queen (1998). With son Adam Stemple, she wrote the Rock ‘n’ Roll Fairy Tale novels Pay the Piper (2005) and Troll Bridge (2006).

Notable works of short fiction include Nebula Award winners ‘‘Sister Emily’s Lightship’’ (1997) and ‘‘Lost Girls’’ (1998). As an editor, Yolen has worked on many books of SF, fantasy, folktales, and retold fairy tales. Her non-fiction includes Touch Magic: Fantasy, Faerie and Folklore in the Literature of Childhood (1981).

Yolen is the most recent recipient of the Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award from SFWA. She won a World Fantasy Award for life achievement in 2009, and was named a grand master poet by the Science Fiction Poetry Association in 2010. She has also received the Society of Children’s Book Writers’ Golden Kite Award (1974), the Christopher Medal (1978), the Garden State Children’s Book Award (1981), a Mythopoeic Society Award (1984), the University of Minnesota Kerlan Award (1988), the Skylark Award (1990), and a World Fantasy Special Award for her editorial work (1986). From 1986-88 she served as president of SFWA, and holds honorary doctorates from six colleges and universities.

Yolen lives in Western Massachusetts, and spends a few months each year in Scotland.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘My father’s family came to the US early in the 20th century from the Ukraine, long before the Nazi era. The family joke has always been if they hadn’t gotten out when they did, they would have been killed by the Cossacks. If they hadn’t been killed by the Cossacks, they would have been killed by Hitler. If they hadn’t been killed by Hitler, they would have been killed by Chernobyl. Good thing they left.

‘‘Eight years before Harry Potter came out, I wrote a novel called Wizard’s Hall, about a boy named Henry. His mother doesn’t think he has any magic in him, but he goes to magic school, and the first thing that happens is that he sees pictures on the wall that move and change. He makes friends with a redheaded boy and a very smart girl, and there’s a wicked wizard who used to teach there who’s trying to destroy the school. (There is no Quidditch.) J.K. Rowling never read my book, but clearly we must have read the same fantasy stories! Those are fantasy tropes, just as writing about interesting candies are English children’s book tropes (see Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang).

‘‘Of course, nothing was as successful as Harry Potter. I love that a children’s book writer made more money than the queen. After Rowling’s groundbreaking success, more kids and adults began reading fantasy, although most of them only wanted to read Harry Potter. Unfortunately, most of the follow-on came from publishers saying, ‘We want you to write a trilogy, or a seven-book narrative like Harry Potter,’ instead of saying, ‘I want your fantasy novel.’ I would get letters from kids who would say, ‘I was very angry with you, I thought you were copying Harry Potter, and my teacher showed me that your book was published eight years earlier. Are you going to sue her?’ No, because we’re all using fantasy tropes. I’ve written a few series, though, like the Great Alta saga – it all started with one book, and then there was more to tell.

‘‘For years I’ve been telling people, ‘I’m not a novelist.’ Yes, I’ve written novels, but I’m basically a poet. I love doing picture books. I write novels reluctantly. However, last year, I was invited to be on a panel for historical novelists in Northampton MA, and I decided the first thing I had to say was, ‘I’m really a short form writer.’ But I figured, before I said that, I’d better go count the novels, and when I got to 60, I stopped. I’m an accidental novelist. An accidental, overachieving novelist.”

…

‘‘The science fiction I read tends to be more anthropological SF, like Le Guin, or alternative science SF, or dystopian. Except for The Martian, which I quite enjoyed. I cheated – I saw the movie first and then I read the book. Much of the science goes over my head. My husband of 46 years was a scientist. When I wrote the Pit Dragon books, I went to him and said, ‘I have to build dragons that can get off the ground.’ Flying dinosaurs, they’re huge, how do we get them to fly? ‘Hollow bones,’ he said. A lot of science fiction, like a lot of fantasy, is hand-wavey – don’t look at the man behind the curtain, that sort of thing. Hard science is not in my wheelhouse. I write about natural science, both in poems and books: I’m fascinated by natural science. Once you get to the heavy lifting, the microscopic, or world-building in outer space, I can appreciate parts of it, but I can’t write it.”

…

‘‘Briar Rose was burned on the steps of the Board of Education in Kansas City. It’s funny. I live in Massachusetts, and Banned in Boston has always been a badge of honor. If you’ve had a book banned in Boston, the book has done really well. Even though it didn’t affect sales badly, I think when you write a story, you want everyone to love it, or be moved by it, or be changed by it, or be riveted by it, and when somebody actually burns it, you feel as though somehow you’re caught in Fahrenheit 451. It’s violent and ludicrous. They took three books out of the library and torched them on a barbecue because they all had gay characters. They didn’t do a bonfire. A bonfire I could get behind. Surprisingly, one part of me really was hurt. That’s my book. I thought, ‘You bastards. You took it out of the library. Why didn’t you go buy a book? Torch your own damn book.’ The idea that we still think, in this day and age, that if you don’t like a book, or a magazine article, or an album, or a person, that you can throw them on a fire, is really hard for me. So one part of me was hurt, and one part of me was horrified, and one part of me wanted to fight back.”

‘‘Briar Rose was burned on the steps of the Board of Education in Kansas City. It’s funny. I live in Massachusetts, and Banned in Boston has always been a badge of honor. If you’ve had a book banned in Boston, the book has done really well. Even though it didn’t affect sales badly, I think when you write a story, you want everyone to love it, or be moved by it, or be changed by it, or be riveted by it, and when somebody actually burns it, you feel as though somehow you’re caught in Fahrenheit 451. It’s violent and ludicrous. They took three books out of the library and torched them on a barbecue because they all had gay characters. They didn’t do a bonfire. A bonfire I could get behind. Surprisingly, one part of me really was hurt. That’s my book. I thought, ‘You bastards. You took it out of the library. Why didn’t you go buy a book? Torch your own damn book.’ The idea that we still think, in this day and age, that if you don’t like a book, or a magazine article, or an album, or a person, that you can throw them on a fire, is really hard for me. So one part of me was hurt, and one part of me was horrified, and one part of me wanted to fight back.”

…

‘‘A lot of new writers – like Holly Black, Kelly Link – are doing crossover books, so that adults can read them with as much engagement as teenagers can. There’s also a new thing called New Adult, the step above YA, for 20- or 21-year-olds, that feels more to me like training wheels. When I was first writing back in the ’60s, and editing at Knopf, that’s when young adult became a genre. Before that they were all just children’s books. Young adult as a category was driven by librarians, because they were already doing it – they were separating out books for the young-adult room where the teenagers went. They weren’t going to sully the children’s room with those rowdy teens, but they weren’t going to have teens reading those sexy irreverent adult books. In those days, there were the Sweet 16 books, but once they started designating young adult as a category, they developed into something called problem novels – a little like ‘disease of the week,’ a story about the girl whose mother is a prostitute, or the boy whose father is a drunk. Those were the problem novels, more problem than novel. Like Afterschool Specials. But the great ones, such as The Outsiders, The Cheese Stands Alone, The Chocolate War, stuff like that, those are still read. Right now in children’s books, you’ve got board books, step-up books, concept books, classic baby books, classic picture books, story books, poetry for children, poetry for teens, middle-grade books, upper-middle grade books, young-adult books, new-adult books, and then you get to adult books. When I was a six-year-old reading books in my parents’ extensive book collection, I read Thomas Mann’s Joseph in Egypt, or anything else I wanted. If I didn’t understand parts of it, I didn’t understand parts of it. If it’s in the house, you can read it. Of course, it’s one thing to have a particular parental unit say, ‘My kid is allowed to read anything,’ but for public libraries it’s different. If all children were let into the adult section, any parents who are unhappy about that would make a huge fuss, even shut down the library.”

…

‘‘Children’s books and young-adult books and fantasy have this in common: the best are written like poems. They have metaphor, they have astonishing lyrical prose, and they work on multiple levels. They are a gateway drug to beautiful literature, and shouldn’t be dismissed. If I want to learn something new, I’ll start with a really good children’s book on the subject, and then move on to an adult book. Half the time I’ve learned most of what I need to know in the children’s book, or the adult book is not as well written, or it’s not as convincing, because it’s throwing stuff at you in order to convince you – but I’ve already been convinced by the poetry.”

Read the complete interview in the March 2017 issue of Locus Magazine. Interview design by Francesca Myman, Jane Yolen photo by Liza Groen Trombie.

I remember, in high school, having assigned reading of a biography of George Fox, “Friend.” Normally, I tended to dislike what I was required to read for school—but, having enjoyed some of Jane Yolen’s work published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and seeing her name as author on the book, led me to have a much fonder memory of the book than others. Thanks for the memories.