The Fogeys of July: A Review of Independence Day: Resurgence

by Gary Westfahl

by Gary Westfahl

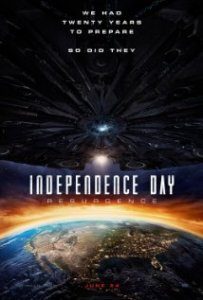

Since I was recently complimented at a conference for writing “honest” film reviews, I feel obliged to begin this one by conveying my honest reaction to Independence Day: Resurgence: although I was bored and appalled by the original Independence Day (1996), and utterly baffled by its tremendous popularity, I somehow found its belated sequel to be surprisingly engaging, even moving, despite some obvious issues in its logic and plausibility. Perhaps this indicates that I am finally becoming senile, unable to distinguish between worthwhile entertainment and reprehensible trash; perhaps this is a sign of the times, so that a film modeled on a film that stood out in 1996 for its risible inanity and clumsy manipulativeness now seems, amidst scores of similar films, merely typical, or even a bit superior to its lamentable competitors. Perhaps, though, it is simply a better film than its precursor, the theory that merits some extended exploration.

Before any discussion of how this film differs from its precursor, though, one should begin by acknowledging its key similarities. Twenty years after their first invasion, the evil aliens have launched another assault on planet Earth, arriving in ships that are “bigger than the last one” (a point made at least twice). Though we see more of them, and learn more about their culture, the aliens remain implacable enemies, determined to annihilate humanity, with the ultimate goal of draining the Earth’s molten core to obtain needed energy and render the planet uninhabitable. Despite their amazingly advanced technology, it is again determined that they have one key weakness, and by means of a desperate maneuver that scientist David Levinson (Jeff Goldblum) accurately describes as a “Hail Mary,” and the heroic efforts of several disparate characters, the human race is ultimately able to prevail. All of this, of course, mostly represents what everybody in the audience already knows before the film starts.

Still, the first film’s battle against the aliens was largely an all-American affair, and there were inept attempts to appeal to the audience’s patriotic fervor by absurdly likening resistance to the aliens to the United States’ struggle for independence, as commemorated by the titular holiday. Yet this film has a distinctly international spirit: new President Lanford (Sela Ward) emphasizes in a speech that the invasion brought the nations of the world together, resulting in twenty years without any significant conflicts – humanity “rose from the ashes as one people, one world”; former president Thomas Whitmore (Bill Pullman) similarly observes that the world is “unified like never before,” a condition that is “sacred” and thus worth preserving; a team of space pilots from different nations is identified as the International Legacy Squadron; before deciding upon one attack, President Lanford first consults with a “Security Council” that includes the leaders of France, Britain, and Russia; Levinson travels to central Africa as part of a United Nations Research Mission; and in a radio message, General Adams (Wiliam Fichtner) explicitly addresses all the world’s people, stating that “no matter our differences, we are all one people.” The cast also has an international flavor: a journalist notes that China made especially important contributions to developments in space, and two major characters are Chinese – pilot Rain Lao (Angelababy) and her uncle Jiang (Chin Han), commander of the moon base; they even speak a few lines of Chinese. And although one might dismiss this as pandering to an increasingly valued international market, it is less easy to attribute cynical motives to the prominent roles played by a courageous African warlord, Dikembe Umbutu (Deobia Oparei), and a French psychiatrist, Catherine Marceaux (Charlotte Gainsbourg), who studies individuals who have interacted with aliens. The trend toward cross-cultural cooperation may even extend to the stars; for while the attacking aliens are irredeemably evil, so “there can be no peace” with them as Lanford notes, there are growing intimations of another, more benign alien race that might become humanity’s allies.

Second, Independence Day seemed downright silly in imagining that the human science of 1996 could somehow overcome the vastly superior technology of the alien invaders; but in this film, humanity has employed knowledge garnered from the aliens to forge a viable space program, with bases on the Moon and a Saturnian moon, fast spaceships powered by “fusion drives,” and formidable new weapons like “cold fusion bombs.” All of this makes a possible victory over the aliens seem a little more believable, and it provides the film with an unusually distinctive setting, an alternate world of 2016 wherein an alien invasion has triggered tremendous advances in some areas but not in others. So, one sees a fusion-powered “space tug” landing next to gasoline-fueled cars and school buses that look exactly like the ones now on the roads.

Third, even though the film industry increasingly strives to appeal to the young, Independence Day: Resurgence is an extended celebration of old people – which might explain why this old reviewer was unexpectedly fond of it. One might attribute this to the fact that director Roland Emmerich and his returning collaborator, writer Dean Devlin, manifestly loved their earlier film and were determined to reference it as much as possible by bringing back, or at least mentioning, every single one of its major characters, all of them now senior citizens. Only two surviving characters do not reappear: Captain Steven Hiller (since Will Smith declined to participate), and Levinson’s ex-wife Constance Spano (who would have complicated Levinson’s budding romance with Marceaux). But Levinson, ex-president Whitmore, Levinson’s father Julius (Judd Hirsch), Hiller’s wife Jasmine Dubrow (Vivica A. Fox), General Grey (Robert Loggia), eccentric scientist Brakish Okun (Brent Spiner), and his friend Dr. Isaacs (John Storey) all reappear, while characters who could not return are remembered in other ways – Hiller in both a portrait and a photograph, and Whitmore’s deceased wife in the name of the Marilyn Whitmore Hospital where a comatose Okun has been residing.

However, whenever there is a lengthy interval between the production of a film and its sequel, the typical tendency is to relegate the elderly returning characters to minor roles and focus most of the attention on new, younger protagonists; thus, it is not surprising to learn that Dubrow is quickly written out of the film and Grey is only briefly observed, sitting in a wheelchair and saluting the current and former presidents. Yet Emmerich makes Goldblum’s Levinson the true star of his sequel, even though Liam Hemsworth (playing pilot Jake Morrison) officially gets top billing; tellingly, while both men play a role in humanity’s inevitable victory, it is Levinson, not Morrison, who is told, “Well done!” Furthermore, Whitmore, Julius Levinson, Okun, and Storey are just as prominent, or even more prominent, than they were in the first film. And while Goldblum, long one of my favorite actors, is excellent as always, the other returning actors, who essentially phoned in their parts in the first film, provide stronger performances here, as if recognizing that it might represent their last chance to be in the limelight. And this might serve as a wake-up call to Hollywood executives: for if a director ever suggested out of the blue that she wanted to make a major film starring Jeff Goldblum, Bill Pullman, Judd Hirsch, and Brent Spiner, she would be laughed at derisively: you can’t make a successful film with those decrepit has-beens – you need hot young talent! Yet this film works very well with its fogeys at the forefront, and Goldblum, Pullman, Hirsch, and Spiner are only a few of the many aging, out-of-work actors who might shine again if given the opportunity.

Yet it is not only their visibility, but their importance to the plot, that makes this film’s older performers so distinctive; for they represent the film’s brain trust. Levinson and Okun in particular are the ones who figure things out and enable humanity to mount a successful defense, and Whitmore deduces one key fact about the aliens before anyone else. (A subtle but telling sign of his intelligence: when we first see him, he is reading a history of the Luftwaffe; in other words, he is studying the aerial tactics of a defeated foe who made a stunning counterattack, precisely what he is anticipating.) Even Julius Levinson, who was mainly an irritant in the first film, emerges as an insightful hero in assisting some children and recognizing that taking over an abandoned school bus represented their best way to reach safety. And the film did not have to entirely rely upon its geezers to do all the thinking: responding to the obvious need for fresh new characters, the screenwriters might have provided Levinson and Okun with bright young assistants to help with their research and perhaps contribute a few ideas. Instead, the only new scientist is the forty-something Marceaux, while the film’s younger characters – Morrison, his friend Charlie (Travis Tope), Hiller’s son Dylan (Jessie T. Usher), Lao, and Whitmore’s daughter Patricia (Maika Monroe) – are merely pilots, whose basic role is to do whatever the geezers tell them to do (though Patricia is first working as a presidential speechwriter before she returns to the cockpit). To illustrate their insignificance, one could easily edit all of them out of the film and create an entertaining, 70-minute film starring Goldblum, Pullman, and Spiner; but it is impossible to imagine a film without those elderly characters.

In sum, I may have especially appreciated this film because it atypically allowed its older performers to dominate the proceedings; but in another respect, Independence Day: Resurgence is an all-too-typical Hollywood film in insisting upon this bedrock principle: people are inspired to be heroic only by the perils of their friends and relatives. The film gets off to a slow start primarily because it must painstakingly establish the emotional relationships between characters that will later explain their actions; the pilots at times seem more interested in saving each other’s lives than in killing aliens; to motivate a group of people to attack the aliens, one character announces, “we all lost someone we love – so let’s do it for them! Make them pay!”; Umbutu says to himself that he is driven to kill aliens as a way to avenge his deceased brother; Julius Levinson seemingly grows attached to some orphaned children because they represent the longed-for grandchildren that his son David never provided; and to explain to his daughter why he is embarking upon a suicide mission, Whitmore tells her, “I’m not saving the world, I’m saving you.” One incident in particular seems an illustration of these characters’ misguided priorities: though undoubtedly needed elsewhere, Dylan at one point ignores his orders and flies off to a hospital – to rescue his mother.

In the real world, however, society depends upon soldiers, police officers, and firefighters who are willing to work long hours and risk their lives to benefit complete strangers; one reason they are so effusively praised is the genuine selflessness of their actions. We would live in a sad, dysfunctional world if soldiers only fought to save their friends and relatives, police officers only investigated crimes that affected their friends and relatives, and firefighters only put out fires that were threatening the homes of their friends and relatives. Yet screenplays must always be carefully written to provide characters with some intensely personal motive for everything they do, even when their actions would never be sanctioned under ordinary circumstances. Consider this: suppose a huge wildfire is raging, threatening to destroy an entire community, and every firefighter is urgently needed to keep it under control; yet one firefighter has abandoned his post in order to rush home and make sure that his mommy is okay. That firefighter would be universally condemned; yet in this film, when Dylan Hiller does the same thing, we are supposed to admire him.

Indeed, Goldblum’s Levinson is so appealing, in large part, because he is the one character in the film who seems entirely focused on what he should be focused on, namely, saving the entire human race, not saving someone who is near and dear to him. At no time in the film does he exclaim, “Oh my gosh! Where’s my dad? I gotta go save my dad!”; he finally encounters his father solely as a result of the most improbable of the film’s many improbable coincidences. In sharp contrast, the film’s other protagonist, Hemsworth’s Morrison, proves harder to like because, throughout an invasion that may exterminate humanity, he is primarily worried about protecting his best buddy Charlie, ensuring the safety of his fiancée Patricia, and rebuilding a relationship with his estranged former friend Dylan.

Another reason to be unenthusiastic about this film is its aforementioned “logic and plausibility.” The credits conspicuously fail to include a “Science Advisor,” and while one Nick Herman is listed as a “Researcher,” connected to the Art Department, it remains unclear precisely what he was researching, or why he was qualified to conduct this research. Certainly, his work did not involve space travel: as in the Star Wars films, characters routinely board spaceships without a protective spacesuit in sight – they are only observed when Levinson and Marceaux are walking on the lunar surface; space travelers never experience zero gravity; and no effort is made to depict the Moon’s lower gravity. (If Dylan had actually punched Morrison on the Moon, he would have been flung across the room instead of falling to the floor.) The film also completely ignores the economics of space, as it seems extremely unlikely that the governments of Earth could have afforded to build all of these spaceships, satellites, and planetary bases while simultaneously funding the complete reconstruction of the innumerable buildings and structures destroyed during the first invasion, a project apparently completed in twenty years.

More serious questions arise regarding the physiology and behavior of the aliens. First, since everybody hates insects, and everybody routinely kills unwanted insects, it makes sense for filmmakers to fashion their hostile aliens to resemble insects (as in the Starship Troopers films and Edge of Tomorrow [2014 – review here]). Further, since insects like ants and bees entirely rely upon a single queen, that would provide insect-like aliens with a convenient vulnerability, which this film ruthlessly exploits. Yet it seems improbable that an advanced technological civilization could evolve within, and retain, such a social structure, and if it did, its queens would surely be intelligent enough to recognize this as a potential problem and equip all of their invasion forces with two queens – or five queens. It is also a remarkable coincidence that these outré creatures are able to thrive in the gravity and atmosphere of Earth, as their energetic hostilities demonstrate. As for the notion of obtaining energy by drilling into large inhabited planets and extracting their molten cores: surely, a truly advanced culture could find an easier and more efficient way to get all the energy they need, especially since this one has already mastered controlled fusion, fueled by the most abundant element in the universe, hydrogen.

A final complaint: though they waited a respectable twenty years before producing a sequel to the first Independence Day, it is disheartening to hear that Emmerich and Devlin are already working on Independence Day 3; independent verification of this fact is hardly necessary when a film concludes by explicitly whetting the audience’s appetite for an even bigger and better battle royal: “we are going to kick some serious alien ass!” Yet such plans seem premature when it is by no means assured that the second film will equal the success of its predecessor. (After all, I hated the first film, but everybody else liked it; perhaps, because I liked the second film, everybody else will hate it.) Further, in contrast to the well-thought-out universes of Star Trek and Star Wars, the underpinnings of this franchise seem far too shaky to sustain an extended series of films. If Emmerich is actually interested in venturing beyond his comfort zone (as suggested by the uncharacteristic Stonewall [2014]), I would suggest, as an alternative, making a sequel to another science fiction starring Jeff Goldblum, the surprisingly entertaining Earth Girls Are Easy (1988), with Goldblum appearing as the older and wiser mentor to a new generation of amorous alien teenagers. Such alien visitors, arguably, are just as plausible as the relentless horrors of the Independence Day films, and more charming as well.

Interesting counterpoint to the universally negative reviews.

I found the movie to be mediocre, but mostly in the same way many Hollywood tentpoles since the original ID4 came out have been lousy: very little plot, lots of explosions. Indeed, one argument about why the older characters mattered so much is that without the Levinsons, Whitmore, and Okun, this had all the storytelling and character development of an arcade game.

One note on the fogey side: Robert Loggia died of Alzheimer’s last year, so his inclusion wasn’t token whatsoever.

I had enjoyed the first ID4 movie way back when, but I recognized it for what it was: a live-action Hollywood equivalent of Japanese anime, as well as a wish-fulfillment power fantasy of poor underdogs triumphing over supremacist bullies. This was pre-911 and pre-Bush/Cheney, of course.

Gary Westfahl is not wrong in his assessment of both ID4s, as well as the Hunger Games book trilogy/movie quartet. However, I have noticed a certain similarity in both franchises. In the Hunger Games, the repressed and exploited children in a post-America tyrant state happen to be these narcissistic, playing-the-victim golden kids. In the Independence Days, that role is filled by the human population of Earth. Sometimes one can see how insignificant Man is, not by the size and complexity of the universe, but by his own hubris.