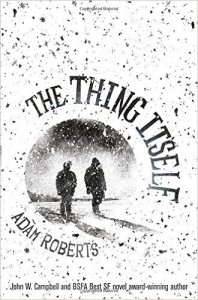

Paul Di Filippo reviews Adam Roberts

The Thing Itself, by Adam Roberts (Orion/Gollancz 978-0575127722, £16.99, 368pp, trade paperback) December 2015

The clever formal construction of Adam Roberts’s new book (God bless his craftsmanly productivity, which keeps us fans reliably supplied with a fresh annual fix, year after revolutionary year) is just part of the novel’s enigmatic allure. The first thirty pages are a complete narrative arc, a short story, more or less, that could have appeared in a volume of Orbit, say, during that anthology’s prime years. Two young researchers, Roy and Charles, are doing radio telescope SETI research at an isolated Antarctic base in the year 1986. We hear the story from the POV of Charles, who seems a rational easygoing fellow. His partner, Roy, however, is a feverishly unstable dreamer fixated on the work of Kant, specifically The Critique of Pure Reason. Roy believes that the old tome of dense, complex philosophy contains the secret answer to the Fermi Paradox about the prevalence of intelligent life in the universe. After much taut, emotional and blackly comic interplay of an Edward Albee nature, a mortal crisis, involving, perhaps, some actual aliens, is reached and survived. Has Roy indeed solved Fermi’s riddle? And at what cost?

The clever formal construction of Adam Roberts’s new book (God bless his craftsmanly productivity, which keeps us fans reliably supplied with a fresh annual fix, year after revolutionary year) is just part of the novel’s enigmatic allure. The first thirty pages are a complete narrative arc, a short story, more or less, that could have appeared in a volume of Orbit, say, during that anthology’s prime years. Two young researchers, Roy and Charles, are doing radio telescope SETI research at an isolated Antarctic base in the year 1986. We hear the story from the POV of Charles, who seems a rational easygoing fellow. His partner, Roy, however, is a feverishly unstable dreamer fixated on the work of Kant, specifically The Critique of Pure Reason. Roy believes that the old tome of dense, complex philosophy contains the secret answer to the Fermi Paradox about the prevalence of intelligent life in the universe. After much taut, emotional and blackly comic interplay of an Edward Albee nature, a mortal crisis, involving, perhaps, some actual aliens, is reached and survived. Has Roy indeed solved Fermi’s riddle? And at what cost?

We cut jarringly in the next section to the year 1900, during which a pair of male lovers, Albert and Harold, are taking a leisurely Grand Tour of Europe. There’s just one hitch to their relaxation: Harold, after perhaps too-intense an involvement with the new book by Mr. Wells, The War of the Worlds, has begun to hallucinate. “The sweeper was moving piles of…tadpole-like beings, each head the size of a bowling ball and the colour of myrrh, the tails double-bladed and freaked with silver and blue.”

Part three jumps us back to Roy, in the present. His devastating experiences at the South Pole have left him spiritually and physically wounded—and literally haunted, by the image of ghost boy. Unable to maintain a professional job or relationships with women, he is leading a shabby dead-end existence as a trash man. Then, one morning, a beautiful woman named Irma shows up on his doorstep and announces that he has been summoned by a mysterious Institute that needs his expertise.

At the Kafkaesque Institute, he learns that Roy—immured in a sanitarium like some malevolent Magneto all these years—was truly onto something. The folks at the Institute have advanced Roy’s ideas to a certain degree, but still need Roy’s unique insights. Charles, at Roy’s explicit request, has been hired to broker that help. Reluctantly, he consents. And is plunged into an Alice-in-Wonderland scenario that involves a mordant and duplicitous Artificial Intelligence, Hitchcockian double-crosses and mad pursuits (with some antics from The Prisoner on the side), as well as nothing less than an existential recalibration of the nature of reality and the cosmos. The book—with those baffling yet ultimately organic and coherent historical sections, some in the future, continuing to alternate with the realtime adventure—runs pell-mell to a devastating conclusion.

Despite some peripheral and surface allusions to John W. Campbell’s famous tale of a shape-changing polar alien, Roberts is not really out to give us a First Contact story. The mode he is working in is Conceptual Breakthrough spliced with Odd John/Mutant/Midwich Cuckoo/Jack of Eagles shenanigans. It’s a potent mix indeed. Roberts is not afraid to lay on vast swatches of dialogue discussing matters of deep ontological meaning. Like Kim Stanley Robinson, he relishes what others might regard as non-plot-serving infodumps. But his talent with conceptual juggling and the sheer clarity of his prose makes such stretches fascinating, integral and easy to digest.

In crafting the character of Charles Gardner, Roberts gives us an utterly believable antihero whose fumbling actions bespeak a completely human set of both virtues and flaws. Like some wounded Fisher King, Charles would like to redeem humanity, but is held back by his inner turbulence and angst. Ultimately, he pushes himself beyond his worst aspects into some kind of redemptive victory.

And in Roy Curtius, Roberts gives us a Faustian figure who is neither wholly reprehensible nor vile, but rather a fellow seduced by the dark side of his own nerdy genius. Together, the two enact what is surely the best cat-and-mouse game of this nature since Frank Robinson’s The Power, a hidden template, I think, for this book.

In the end, though, Roberts transcends the simpler SF of Robinson’s era, and exhibits the same postmodern ramping up that he has brought to a dozen other different SF “power chords.” If Greg Egan and Stanislaw Lem had conspired to rewrite John D. MacDonald’s The Girl, the Gold Watch and Everything, the result might have been half as ingenious and gripping and funny and scary and invigorating as The Thing Itself.