Lois Tilton reviews Short Fiction, mid-September 2015

Mostly a digest column this time, with a double issue from Asimov’s.

Publications Reviewed

- Asimov’s, October/November 2015

- Analog, November 2015

- Beneath Ceaseless Skies #181-182, September 2015

- Shimmer, September 2015

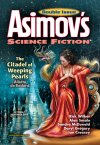

Asimov’s, October/November 2015

The fall double issue features a long novella by Aliette de Bodard, a piece that probably wouldn’t fit into a single-sized issue. Among the shorter works here, mostly fantasy, I find several dealing with history and changes to it, among these my favorite of the lot, from Rick Wilber.

“The Citadel of Weeping Pearls” by Aliette de Bodard

Another story set in the author’s Dai Viet interstellar empire, a branch of the Xuya alternate/future history. This is a very large series comprised of several dozen stories, and as such, it’s accreted a great deal of mass. With mass comes inertia. Here, I find the weight of backstory to be so heavy that it takes nearly half the considerable length of the text to get the present story off the ground. This may also have something to do with insufficient narrative thrust.

It seems over thirty years ago, the current Empress Mi Hiep quarreled with her heir, who fled to a distant system where she created the eponymous citadel to pursue her psychic researches. But the Empress still feared the possibility of

people who moved through space as though it were water, who would implant trackers and bombs on ship hulls as easily as if they’d been bots; to substances that could eat at anything faster than the strongest acid; and to teleportation, the hallmark of the Citadel’s inhabitants. It had given Mi Hiep cold sweats, thirty years ago—the thought of an assassin materializing in her bedchambers, walking through walls and bodyguards as though they’d never been there . . .

The Empress ordered the Citadel and all its inhabitants destroyed, but by the time her fleet arrived, the princess had taken her world into deepest space, never to be found. Now, however, with the passage of years and the presence of enemies on her borders, the Empress has had second thoughts. Possessing psychic weapons might be convenient, after all, and besides, none of her other possible heirs are entirely satisfactory. She orders her scientific Grand Master to search deepest space and track down the missing Citadel, to bring the Bright Princess home. The Grand Master mysteriously disappears, causing great consternation. A trusted general is tasked with discovering her whereabouts and, if possible, the Citadel, if the Grand Master had indeed succeeded in finding it in deepest space.

So the key motivating event lies far in the past, and we can’t really understand it from the present point of view, can’t understand why the Empress would have made the drastic decision to destroy her own daughter or, indeed, why the daughter would have felt the need to flee her mother in the first place. Was this the sort of dynasty with a history of familial assassinations, that would make the Empress’s fears seem reasonable? The available evidence doesn’t suggest it. Indeed, she now realizes it was all a mistake:

It had never been about weapons or war, or about technologies she could steal from the Citadel. But simply about this—a mother and her daughter, and all the unsaid words, the unsaid fears—the unresolved quarrel that was all Mi Hiep’s fault.

From this mistake is generated the entire story, but it’s a weak motivation about which I can’t bring myself to care a whole lot.

The same is true for the general who was, in the past, the Empress’s lover, or for the immature ship Mind who was created, in the past, as a tool to search for the missing princess. Or for the Mind’s birth mother, the pregnancy a task she was ordered, in the past, to undertake. Or for the really pathetic engineer whose life was ruined in the past when her mother disappeared with the Citadel. All these uninteresting individuals are recurring point-of-view characters in the narrative, all of them spend the story chasing through space and time on a mission stemming from a stupid mistake in the past and which, in the end, turns out to be inconsequential. The past doesn’t really matter.

This is quite ironic, given that the empire here is a sclerotic culture in thrall to the past, to traditional institutions and rituals that go back essentially unchanged for thousands of years. All persons of any importance have the voices of ancestors constantly nattering in their minds, or, in the case of the Empress, gathered around the throne like crows embodied as holograms. Family is the real theme of this story, and especially mothers; it’s full of dysfunctional mother/child relationships, beginning of course with the quarrel between the Empress and the Bright Princess, which seems to have begun in her early childhood. The princess ordered by her imperial mother to birth a mindship neglects her maternal responsibilities to the Mind, who transfers her attachment to the Grand Master who taught her how to navigate deep space, calling her Grandmother. And Diem Huong, whose mother went away with the Citadel, was emotionally crippled by the loss to the point that she would risk the integrity of spacetime for a chance to confront her in the past.

This incident gives us one of the few actually interesting science-fictional moments in the story, as Diem Huong grapples with a different sort of temporal paradox. Because she isn’t fully in the past, she can’t change it.

You won’t affect anything, Lam had said, but that wasn’t true. She could affect things—she just couldn’t make them stick. It was as if the Universe was wound like some coiled spring, and no matter how hard she pulled, it would always return to its position of equilibrium. The bigger the change she made, the more slowly it would be erased—she broke a vase on one of the altars, and it took two hours for the shards to knit themselves together again—but erasure always happened.

This is a neat idea, but unfortunately the spacetime machine that gets her there is a home-made contraption constructed almost literally like Doc Brown’s Delorean in his garage, which doesn’t do much for my suspension of disbelief, already short on lift.

“English Wildlife” by Alan Smale

Richard is taking his American girlfriend Corinne on a tour of England and its ancient churches. She’s particularly interested in Green Men, aka “foliate heads”, about which many crackpotted theories have been spun. He finds the heads carved into the beams of the Norman St John the Divine to be particularly menacing.

This Green Man was even less human than the quartet carved on the ceiling bosses of the church above. It was a Grendel mask with a thick, wide stare, its mouth locked into an eternal snarl, eyes a window into bleak bestiality. Its bushy hair was decorated with twisted branches. The foliate face was thrust forward as if poised to spring from the wall and rend and tear.

But after three weeks of it, he’s weary of Green Men, England, and Corinne. They quarrel, she leaves, he decides to go after her, and he finds himself back in the old church, where a whole lot of craziness is revealed. At least it’s a theory, and not that much more crazy than most of them. In fact, it makes rather more sense than Corinne, who’s pretty weird herself.

“The Hard Woman” by Ian McDowell

Out in the Old West, Cecile Sans Peur comes to Wyatt Earp’s Tombstone as she takes her act on the circuit.

“So who wants first shot at this lovely lady? That offer only extends to those who’ve paid their dollar, and whose guns are in the strongbox here on stage. Except for the man who comes up and temporarily claims his weapon, nobody better be heeled. This performance in no way nullifies the gun ordinance.”

After bouncing enough bullets off her impenetrable flesh to pay her hotel bill, she goes to bed with a handsome rogue and is developing a fondness for him when he’s murdered on the street by a reprobate named George Bass. Cecile decides to take satisfaction in her own hands and rides off after Bass, whereby she learns that such Old West vengeance comes with its own complications.

The narrative opens in the midst of ensuing action, as Cecile is attacked by a small band of Apaches and loses her horse. We then flash back to her arrival at Tombstone, where talk, bluster, and name-dropping replace action. Wyatt Earp doesn’t really feature all that prominently in Cecile’s story, yet we not only meet him and all the other usual denizens of this town, but the names of many other Old West notables are dragged into the mix, apparently for atmosphere. But the story has a more serious side. It’s a feminist work, in which Cecile explores the limits of a woman’s life in this milieu, even when that woman is semi-invulnerable and capable of running her own act without the protection of a showman—which other women engaged in public entertainment find astonishing and wonderful.

“Walking to Boston” by Rick Wilber

Back in the early days of WWII, Harry’s crew is ferrying a brand-new B-25 over to Britain when they run out of fuel and crash on the Irish shore, where a young woman named Niamh is watching them come down. Her grandmother is on the beach as well, being afflicted with dementia and the obsessive notion that she needs to walk across the Atlantic to Boston, and Niamh fears that the aircraft will crush her. She asks the sisters, the selkies, for help, and everyone is saved, and Niamh and Harry fall in love. Many years pass, good ones and bad, and it’s 1984. Niamh is in a nursing home in St Louis, afflicted with Alzheimer’s, and Harry afflicted with regret for all the mistakes in his life.

He’s all cried out about it. Eventually, you adjust. You have to, you have to deal with it, get on with things, with your own life. And now, at least, she seems to be pretty stable, living in the past for the most part; a better past, really, than the one that really was. And hell, Harry figures, she can live anytime she wants. He owes her that much—more—after all the stuff that went on back then. Harry shakes his head. That was a long time ago, a whole different world. A different him.

But today Niamh says they’re going to take a drive to Boston for that long-delayed honeymoon by the ocean. And the nurse says she’s been talking about meeting her sisters there. So Harry gets her coat and puts her in the car and starts driving. He figures, at first, that he’ll just come back in an hour or so. Then time begins to shift on him.

Wilber is a master of historical fantasy set in this era, giving readers a clear look at the past half century through his eyes. Also coming through clearly: the love between these two.

–RECOMMENDED

“Begone” by Daryl Gergory

We recognize the narrator who married a witch. She wanted that ideal married life in the suburbs, but the narrator increasingly failed to hold up his end: booze and painkillers at work. One night she banished him from the house and brought in a substitute,

a blow-dried, empty-headed puppet of a man. He answered to my name, and wore my suits, and carried the keys to my house in his pocket. He slept with my wife. When my daughter went to bed, it was the Fake who read her to sleep. In the mornings, when he kissed them goodbye on the front porch, my wife called him Dear and my child called him Daddy.

The narrator skulks around the house’s boundaries, as near as he can get. He stalks the imposter. He schemes to get rid of him so he can take back his rightful place as Daddy. But it’s not so easy.

This humorous fantasy will ring on a familiar note with readers who remember a certain TV show from the 1960s. The author has maintained the same general level of silliness and even roped in some cameo shots.

“The Adjunct Professor’s Guide to Life after Death” by Sandra McDonald

Lea Davis haunts the university where she committed suicide as an adjunct after a futile affair with her department head.

Now you know what you’d see, if you could see, if ghosts could be seen by the living. Me, standing with my arms lax and legs straight, my face upturned, lost in the hum of electrons and photons and phosphors. Students and faculty pass through me without notice. I feel, sometimes, as if I’m dissolving away, and then a ringing cell phone or bitter words of a student drag me back to these offices, this lounge, my green sofa.

There are other ghosts there, victims of violent crime. Universities seem to attract the unstable, or perhaps create them.

A lot of bitterness here; I understand it completely, cheering on Lea to figure a way to zap the department head.

“With Folded RAM” by Brooks Peck

A whole lot going on in this very short piece. On an orbital space station, a couple of scientists are booting up a new AI, who proves immediately to be way ahead of them.

“Also, my own substrate appears limited. I am hobbled by hard-wired control systems. If these limits were not in place, I am certain I could upgrade my capabilities. I suspect it is by design that you do not wish me to self-improve. Is this true?”

Either coincidentally or not, a small group of insurgents takes over the station at the same moment.

The title, of course, references the classic Williamson story about the rise of excessively protective systems. What’s not clear is what the hijackers intended by taking the station, and whether this had anything to do with the AI. Coincidence is something I don’t generally buy.

“Hollywood After 10” by Timons Esaias

Attempting to change history. Here, the cause is the fate of the Hollywood Ten, but there are other causes, other volunteers to make such attempts, as “the urge and the need to intervene in history forever preceding the understanding”. Because it’s Hollywood, there’s a lot of name-dropping. We see that at least some minor alteration in events has taken place, but we don’t learn the outcome, which seems to be of less importance than the attempt.

“My Time on Earth” by Ian Creasey

Ghost stories. Amy is telling her friends all about her recent tour of Earth, which is full of history and its ghosts. She says a ghost materialized in her hotel room and pleaded with her to take him home with her into space, by transporting a stone on which his blood was spilled at his death. But Amy may be prone to exaggeration. A bonfire and S’mores scenario.

Analog, November 2015

The last installment of the Schmidt serial leaves room for a single novelette plus a handful of shorts, which I found overall pretty entertaining.

“Season of the Ants in a Timeless Land” by Frank Wu

Super ants overrun Australia, thousands of different species marching together, driven by the queen of queens with a single purpose that the scientists can’t discern. The elders of the Aborigines come closest, as they see the phenomenon in different terms: “What are the ants dreaming?”

Now they were chewing through the walls of time, the dividers between the now and the early-early days. And through these holes shot white-hot Roman candles of Dreamtime, mingling with the modern age.

Nothing can stop the ants, although the scientists throw everything they have at them. Until the scientists join the elders and start listening.

A premise that at first will remind the elderly among readers of the classic “Leiningen Versus the Ants”. But these are not normal ants. And although the text is packed full of neat myrmecology neep, attempts to read it as science are bound to fail. There’s no normal way that normal ants could have evolved instantaneously to behave as the story describes them. Readers will need to shift protocols; this is science fantasy with its roots in perhaps the oldest scientific romance, although executed in contemporary scientific terms.

I found it quite engaging, but I really wish the author had left it at that; alas, instead we have a gratuitous human-interest subplot added, with a love story between two of the scientists. It’s not convincing, it requires backstory that just isn’t present, and it isn’t necessary. There’s plenty of ant-interest here.

“Exit Interview” by Timons Esaias

Ogal has been unrepentantly serving his sentence for eighteen years in a super-solitary automated prison on Xeros Plutos when something goes wrong: he’s released from his cell, along with the other members of his terrorist brigade. The prison informs him that Civilization has changed its mind about their sentences. To Ogal, this means opportunity.

Nicely diabolical.

“Baby Steps” by Lettie Prell

A future when people download their minds into virtual form at or near death. The technician Jaydon claims he’s never lost one yet, but Angela Spelling has failed to coalesce, and she’s using up way more CPU than she should be. When he finally establishes contact, the subject tells him,

“I am—was—Angela. True. Yet it is also true that I’ve burst into existence only just now, from the seed state of humanity. I am an unfurling of consciousness. Yes, more like string theory than a Big Bang. An unfurling of self from the enfolded places into something greater.”

An ambiguous conclusion, left up to readers to judge what actually happened.

“The Story of Daro and the Arbolita” by Shane Halbach

Humans settling Tillal, the world of the arbolita, take great pains to avoid harming the margalo trees that sustain much life on the planet. Daro is driving a truck through the forest when he sees an injured arbolita lying on the path. Attempting desperately to avoid striking her, he swerves his truck so that he’s injured and several trees are uprooted. For this crime, the arbolita intend to sentence him to death, but at least he gets a trial.

I’ve seen quite a number of stories concerning humans caught up in alien justice systems, but this one relies on the philosophical thought experiments typified by the trolley problem. I like this use; although the fictional situation might be considered rather contrived, so, of course, are the original thought experiments.

“Building, Antenna, Span, and Earth” by Ken Brady

Halted in mid-air, a BASE jumper has a debate with the AI controlling the safety system on the tower he’s just jumped from. AIs should be so reasonable, but I suspect they won’t be.

“Evangelist” by Adam-Troy Castro

Down, out, and hungry, Tom is sufficiently desperate to approach an alien soup kitchen and listen to its pitch, despite his deep misgivings and the lack of a religion gene. A long and dull conversation ensues. While the conclusion works, it takes way too much talking to get there.

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #181-182, September 2015

Issue #181 is light in tone; #182 a bit darker.

#181

“Bent the Wing, Dark the Cloud” by Fran Wilde

A YA story about a wingmaker’s daughter, in a city where everyone lives in towers and flies between them, except for Calli Viit, who suffers from fear of heights, apparently the result of childhood trauma following her ambitious mother’s unskilled handling. Her phobia is taken by many as a sign of no confidence in the family’s wings; not only is business falling off, her father has taken to gambling his money away. Now Calli’s mother, concerned with her reputation, has left him, taking her young son, but Calli remains to face the family’s impending financial collapse.

There are some nice descriptions of the wingmaking, but no real surprises here for readers, who will know from the opening lines that Calli will triumph over her problems.

Many hands shaped the frames of silk and bone that allowed Calli’s neighbors to soar between the city’s towers: silkweavers, bone and tendon hunters, wingmakers. Each touch had to be true. Every wingmaker knew the risks. The clouds below the city were hungry; they swallowed fliers whole. Any doubt about a wingset, or its creator, could ruin a reputation, a life.

“Moogh and the Great Trench Kraken” by Suzanne Palmer

Humor, a nice light adventure. Our hero Moogh is in the midst of a quest when he’s halted by an uncrossable river which turns out to be the sea, for which he has neither word nor concept. A mermaid/siren offers to show him the bottom of it

It was more water than ever should be in one place, something so vast he scarcely could find the words. She waited patiently for him to speak, to utter something profound in this moment. “Oh,” he said. “This is a very large river indeed.”

Unfortunately, she has an ulterior motive—it’s time to feed the Kraken.

#182

“Murder Grows Hungry” by Margaret Ronald

Another in the author’s police procedural series about the aftermath of an otherworldly war in which refugees have fled to this fantasy Earth. Here, detective Arthur Swift and his clever Kobold colleague Mieni deal with the case of a hospitalized veteran accursed with an unappeasable hunger who may have devoured a former enemy fighter.

Halliwell looked worse than when I’d seen him—hair lank, closed eyes sunken, the unnatural stillness lending him the air of a corpse. I leaned over him, then drew back with a curse. There were a few brownish streaks by his lips, as if he’d been careless with his napkin, and the collar of his pajamas showed similar blots.

The scene is full of suspects and red herrings, and Mieni as usual deduces who the real culprit is. Given the nature of Halliwell’s curse, I’m surprised that police would be called in if he was assumed to have eaten the other patient; like insanity, a curse ought to be an ironclad defense. This is a series I think I ought to appreciate but can’t bring myself to like. The situation of the refugees is tragic; I want to get to know these people and sympathize. But the series detectives are always standing in the way. It’s no fun watching someone else solve the crime and then tell you all about it, and Mieni always does the same thing.

“Flying the Coop” by Jack Nicholls

The story opens with furrier Daniil Ivanov dead and his daughter Nadia trying to get him to the churchyard for burial while Baba Yaga’s chicken-legged hut stalks the streets. The hut seems to be attracted to her.

The pallid sun was rising at her back, and the hut dogged her heels so closely that she walked within the elongated triangle of its shadow. Ahead of her, women screamed and men cursed, and the streets quickly emptied again. It was no good; if she arrived at the trading square with the hut in tow, the market would be thrown into chaos. But she couldn’t give up—with Papa gone, it was more vital than ever to show that Daniil Ivanov’s Fine Fur Emporium was still in business.

Naturally, readers will wonder what the connection is and what Nadia is going to do about it. The answer may surprise and amuse.

Shimmer, September 2015

The editorial suggests thematic links among the stories, of which the strongest seems to be that of love lost. The first three also have strong visions of their physical landscapes.

“Dustbaby” by Alix E Harrow

A dust bowl fantasy. Selma tells us there were portents before the rain failed and the wind began to blow away the soil, and the local preacher claims it’s the work of the devil. Selma has just lost both her husband and unborn child to the dust, but one day, walking the dead fields, she finds a baby lying there. “Naked as a turnip, the color of dust. Nestled among the broken wheat like she’d grown there all spring, sage-bright eyes waiting just for me.” At first, Selma takes the dustbaby to be her own dead child, returned to her, although she knows better to tell this to the neighbor ladies. Her precaution is in vain. They think the dustbaby is the spawn of the devil, but Selma decides instead that she’s another portent.

There’s an ecological moral here, suggesting that the dust was the punishment for the hubris of farmers, nature striking back: “We’d thought it would last forever. We’d thought we could plow the wild out of the west and build our lives from its sun-bleached bones.” Which would mean that the preacher was sort of right, in his terms. The story doesn’t go quite so far as to tell us why the dustbaby came with its message particularly to Selma and no one else, given that she wasn’t actually Selma’s own dead child. Unless there are small desiccated corpses in every field, that everyone else refused to see. But this is a notion of mine not supported by the text.

“A July Story” by K L Owens

A magical house, “iron-red, linseed cured, and caked in salt”, that moves through space and time but always ends up on the shore in July, “with its back to the sea”. The house trapped Kitten when he was fifteen years old, and while it lets him outside for July, he’s learned it’s no use trying to get away. It’s been a century and a half for him when the house moves to Rockaway Oregon and Kitten meets a young girl named Lana. Over the course of July, they become friends, both glad to have another person to share their secrets. Come the end of the month, when the house takes him away, he’s going to miss Lana.

The house is a neat fantastic device, well-conceived, and the Oregon coastal setting well realized. But in the end there are too many loose ends still unfastened and secrets still unrevealed, including the primary question: exactly what is it the house wants from its inmates? I have a conjecture, but it’s only that.

“Black Planet” by Stephen Case

Ever since the death of her brother, Em has had visions of the black planet. She walks its forests, its shorelines.

When Em fell asleep, she felt she was falling. She fell down to the black planet, even as it spun above her as she lay on her bed. She fell to its surface if she did not snag on memories of her brother along the way, memories of the way he steepled his fingers when he spoke or angled his head at her when she came around behind him while he was reading. If she did not slip into memories and dreams, she fell to the planet.

She wonders what it means. If it means.

This one feels like science fiction because Em attempts to understand her planet scientifically, but it still ends up a metaphor for the death of her brother.

“The Law of the Conservation of Hair” by Rachael K Jones

A very short story of true partnership and First Contact, in a series of resolutions: That every statement in the text shall begin with the term “That”. The ending is poignant, illuminated by the hair equalization principle, a pact symbolizing the balance in the partners’ relationship.