Paul Di Filippo reviews Three Novellas

Mama & the Hungry Hole, by Johanna DeBiase (Wordcraft of Oregon 978-1877655852, $12.00, 156pp, trade paperback June 1, 2015

Teaching the Dog to Read, by Jonathan Carroll (Subterranean 978-1596067257, $40, 96pp, hardcover) July 31, 2015

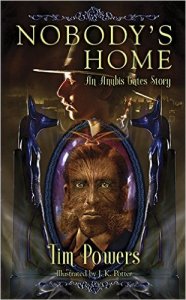

Nobody’s Home, by Tim Powers (Subterranean 978-1596066700, $35, 80pp, hardcover) Dec. 31, 2014

As the SF community witnessed recently, when the folks who govern the Hugo Awards proposed killing the novelette category and thereby generated much controversy, readers and writers have a big emotional investment in medium-length fiction. Novelettes and novellas often seem to fall between the two more distinctive and attention-grabbing polar extremes—short stories and novels—neither one thing nor the other. But as many critics have observed, these types of stories (SFWA places novelettes in the range of 7500-17500 words, and novellas from 17500 to 40000 words) offer many advantages: long enough to build worlds in detail; to explore SF novums thoroughly; and to engage deeply with characters, yet short enough to offer immediate bang for the buck in terms of reader investment and authorial labor. On a practical level, the rise of ebooks has allowed writers to sell their standalone novelettes and novellas instantly, at fair prices, instead of waiting until enough items accumulate for a full collection, as in days of yore.

As the SF community witnessed recently, when the folks who govern the Hugo Awards proposed killing the novelette category and thereby generated much controversy, readers and writers have a big emotional investment in medium-length fiction. Novelettes and novellas often seem to fall between the two more distinctive and attention-grabbing polar extremes—short stories and novels—neither one thing nor the other. But as many critics have observed, these types of stories (SFWA places novelettes in the range of 7500-17500 words, and novellas from 17500 to 40000 words) offer many advantages: long enough to build worlds in detail; to explore SF novums thoroughly; and to engage deeply with characters, yet short enough to offer immediate bang for the buck in terms of reader investment and authorial labor. On a practical level, the rise of ebooks has allowed writers to sell their standalone novelettes and novellas instantly, at fair prices, instead of waiting until enough items accumulate for a full collection, as in days of yore.

Still, the Big Five publishers generally shy away from publishing standalone novellas, leaving the field to specialists such as PS Publishing, Pete Crowther’s fine firm that has probably done more books at this length than anyone. We don’t have handy any PSP novellas for this column, but will consider three from other publishers who also invest regularly in this format: Wordcraft, and Subterranean.

Although Johanna DeBiase appears, from her own online bibliography, to have been selling stories for over a decade, her byline has flown under my radar until now. Surely this fine tale will bring her fresh attention.

Mama & the Hungry Hole is the kind of New Gothic psychodrama that Shirley Jackson or young Ian McEwan or Patrick McGrath might have written. Its naturalism shades by degrees unpredictably into weirdness, and then back again, making you feel that the narrative territory under your feet is always unstable. A fitting enough feeling considering that a giant inexplicable sinkhole is the major “monster,” real and symbolic, in the book.

We open with a short introduction to the strained dynamic between a young girl named Elise and her mother Barbara. There are hints of a past tragedy. (I always think of this fictional maneuver as the “Ada Doom” tactic. In Stella Gibbons’s Cold Comfort Farm, that character constantly reminds everyone that when she was a little girl she “saw something nasty in the woodshed.”)

The next chapter is narrated by Tree, an actual ancient apple tree residing at the edge of a shabby farm. If a tree could indeed tell us what it was thinking, this voice might very well apply. We soon learn that the inhabitants of the farm are Woman and Little Girl. Of course, we savvy readers instantly say, this must be little Elise and Barbara. But no, it proves to be adult Elise and her own four-year-old daughter, Julia. Grandma Barbara will show up later. This neat quick-cut trick provides an immediate sense of dislocation and disorientation that the rest of the tale further stokes. For Elise is continuing to suffer from her childhood trauma, which is impacting Julia’s own development.

The rest of the book unfolds in an unhurried fashion as events slowly tumble down a rabbit hole—or sinkhole, in this case. The end result is a well-etched portrait of one of life’s shattered souls nearly taking down others with her, until love and faith intervene.

Jonathan Carroll’s Teaching the Dog to Read is unlike ninety-nine percent of fantasy tales out there. But of course, this statement is true of Carroll’s entire oeuvre. So let me say this instead: given the stipulation that I have not read every last book by Carroll, I still don’t recall ever seeing a story exactly like this one from his pen before. Always trying something different is a great strategy by which any writer can challenge himself or herself.

Jonathan Carroll’s Teaching the Dog to Read is unlike ninety-nine percent of fantasy tales out there. But of course, this statement is true of Carroll’s entire oeuvre. So let me say this instead: given the stipulation that I have not read every last book by Carroll, I still don’t recall ever seeing a story exactly like this one from his pen before. Always trying something different is a great strategy by which any writer can challenge himself or herself.

Our hero is one Tony Areal (a-real equals not real, natch), and this is his love story, worthy of any romance ever known. Tony is something of a schlub, who lusts after his sexy coworker Lena. He doesn’t stand a chance—until magical things start happening to him, including the arrival of a woman named Alice, who has literally stepped out of a dream Tony had—one in which she claimed to be teaching a dog to read.

As Tony’s life spirals upward into zones of increased bizarreness, he splits himself in two—Tony Day and Tony Night—encounters several avatars of his past incarnations, including a caveman version, and gradually passes into an afterlife fantasy. Oh, yes, some kind of arguably happy ending obtains, illustrating that, indeed “love is strong as death.”

Carroll’s pacing is perfect, as he introduces new elements of oddness one by one. And his insight into matters of the heart is deep. “There are moments in any relationship which can come at the beginning, middle or end, where everything balances on a single word or sentence.” In elegant yet utterly unpretentious prose, Carroll provides one of those pivotal instances right here.

New steampunk from Tim Powers, one of the men who invented the mode? With knockout illustrations by J. K. Potter? (Potter’s career, by the way, celebrates its fortieth anniversary this year. “My first published work was in a 1975 issue of Nils Hardin’s pulpzine Xenophile. It was an intricate ink drawing on the cover of the First World Fantasy Convention commemorative issue.”) What’s not to like!?!

New steampunk from Tim Powers, one of the men who invented the mode? With knockout illustrations by J. K. Potter? (Potter’s career, by the way, celebrates its fortieth anniversary this year. “My first published work was in a 1975 issue of Nils Hardin’s pulpzine Xenophile. It was an intricate ink drawing on the cover of the First World Fantasy Convention commemorative issue.”) What’s not to like!?!

Powers returns with undiminished élan to the universe of The Anubis Gates with a powerful, rapid and compact tale concerning one Jacky Snapp. Miss Snapp, disguised as a lad, is on the trail of the infamous Dog-Face Joe, a serial body-jumper who killed her boyfriend, Colin. Jacky happens to be carrying around Colin’s ghost, which is tied to a relic: ashes from Colin’s pipe. Staking out a likely haunted spot in benighted London, Jacky encounters Harriet, another ghost-ridden maiden. Together, sidekick and warrior, the two must face a number of perils in this exceptional evening, ending up on the barge of the infamous ghost-chaser Nobody, who proves to be both more and less than human.

As always, Powers is the master of presenting backstory in incremental bits that not only serve to gradually illuminate all his mysteries, but to add emotional resonance to events already described. You almost always have to turn back a few pages to re-savor passages in a new light, when reading a Powers tale. It’s a special kind of narrative magic.

Powers has written about ghosts perhaps more than any other contemporary fantasist, and at this point he has accumulated what amounts to a textbook of ghostly science, mostly of his own invention. You would think he had run out of novel ideas by now, but you would be far from the truth. Not only do we get introduced to “ceneromancy,” magic through an ash-based substance, but we also learn about this phenomenon, among many other spectral events: “Ghosts from upriver get snagged here, God knows why, like leaves caught in a drain, and when a whole lot of ’em clump up, they make something like a man…”

This pendant to a larger history showcases both Powers’s immense talents, and the valuable role that novellas can play in a field devoted otherwise to Big Sagas and Short Sharp Shocks.