“It’s Time to Go Home”: A Review of Gravity

by Gary Westfahl

by Gary Westfahl

Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity is not only an excellent movie that people should see, but also an excellent movie that people need to see, to learn about what they have mostly been missing in the last half century of films about space travel – namely, the actual experience of living in space. True, there have been other “spacesuit films” that I have examined at length, but it is hard to think of another film that so relentlessly forces viewers to endure the burden of wearing a spacesuit, the clumsiness of even the simplest movements in zero gravity, the chilling environment of a vast, empty cosmos, the constant threat of instantaneous death, and the daunting loneliness of being isolated within metallic quarters that are far from home. This is a film that offers no cheery interludes in comfortable surroundings, no flashbacks of fondly remembered moments on Earth; it is a film about space, and except for one concluding scene, a film that takes place entirely in space. As if to inform his audience immediately that this is not another film like Star Trek or Star Wars – at best, wildly optimistic projections of the distant future of space travel; at worst, pernicious lies about its inescapable realities – Cuarón begins his movie with some textual reminders of the features of space: temperatures far below zero, no sound, no atmosphere, and so on. The final comment, “life in space is impossible,” is both literally accurate and rich with broader implications that emerge as the suspenseful story rapidly unfolds.

This announced commitment to absolute accuracy provides Gravity with an energy and sense of purpose that I, for one, found lacking in Cuarón’s previous film, the multiple-authored Children of Men (review here ); yet it is scientifically suspect in one respect which is unfortunately hard to overlook, since it is the basis of the plot devised by Cuarón and his son and co-writer Jonás Cuarón. As noted, space is vast, and the director regularly strives to convey that vastness with long shots of tiny astronauts and structures against the backdrop of an immense Earth or field of stars; yet his story posits that space is cramped and cozy. That is, while the problem of human-generated debris in Earth orbit is real and growing, it is extremely unlikely that the debris from one satellite’s explosion would immediately endanger any other orbiting vehicle. It is even more unlikely that such debris would set off a “chain reaction,” smashing into other satellites to create massive waves of debris that quickly destroy every large structure in Earth orbit; for as Douglas Adams reminds us, space is so “vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big” that the odds are always heavily against space collisions. Further, after Cuarón’s improbable disaster claims its first victim, the space shuttle Explorer, its surviving astronauts, Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) and Matt Kowalski (George Clooney), aren’t too worried, because they can see a tiny light in the distance, the International Space Station, so all Kowalski has to do is point his suit’s jetpack in that direction and fly over to it; later, an astronaut uses a Soyuz capsule to make a similar journey from the ISS to another pinpoint of light, the Chinese space station. But in the first place, it is extremely unlikely (again) that all these orbiting objects would happen to be so close to each other at one time, and the three-dimensional movements of vehicles in space are so complex that it is impossible to rendezvous with a spaceship simply by looking at it and pointing your vehicle in that direction. (There is a reason why Buzz Aldrin was given a doctoral degree in astronautics for studying the enormous difficulties involved in “Line-of-Sight Guidance Techniques for Manned Orbital Rendezvous.”)

Still, even if one can quibble about these implausibilities, Cuarón is unflinchingly accurate in conveying the many hardships and hassles of living in space (guided by his official “astronaut adviser,” four-time astronaut Andrew Thomas). At any moment, a piece of debris might hit your faceplate, and you will die. Tasks are harder in zero gravity because sudden movements cause violent lurches and your tools float away; as one inconsequential but emotionally charged reminder of this disorienting state, Stone starts crying in one scene and her tears, instead of rolling down her cheeks, drift off into space. Operating any space vehicle requires a complicated series of actions; pushing the wrong button might prove disastrous; and to stay alive, you are entirely dependent upon machines that must function perfectly at all times. Minor accidents escalate into catastrophes; so, as Stone hurriedly floats through the ISS, a small object hits the wall and starts a major fire (a problem that actually afflicted the Mir space station). Spacesuits run out of oxygen, threatening suffocation; space vehicles run out of fuel, leaving you stranded in space. And if you get in trouble, you need to deal with it yourself, since no one is capable of launching the sort of timely “rescue mission” that Kowalski longs for (which may be the point of the song he loves listening to, Hank Williams, Jr.’s “Angels Are Hard to Find”). When the spacesuit films of the 1950s first focused on such hazards of space travel, the ironic complaint was that these “documentary-style” films were dull and undramatic; in fact, they were clumsily offering a different kind of drama, which Cuarón executes masterfully, the drama of struggling to survive in a harsh environment, and this can be just as involving as treacherous schemes and prolonged fistfights. Indeed, when you are facing an opponent who is as powerful and merciless as outer space, worrying about some weapon-wielding villain is just plain silly.

As she deals with one problem after another in her desperate effort to return to Earth, Stone at one point exclaims “I hate space!” And, since her feelings seem perfectly understandable, the film must confront the question of how people can deal with the overwhelming pressures of space travel. One answer is provided by Kowalski, who treats everything like a joke and never seems bothered by any setbacks. While addressing some challenging task, his recurring comment is “Houston, I have a bad feeling about this mission,” purportedly because it reminds him of some outlandish experience he had on Earth, which he proceeds to relate. All he claims to worry about is his drive to beat the actual record for total time spent spacewalking held by Russian astronaut Anatoly Solovyev (16 spacewalks, 82 total hours). Even as their situation seems more and more dire, he continues to insist that there is nothing to worry about; for example, using a space capsule to get home is easy: “You point the damn thing at Earth – it’s not rocket science.” His attitude appears to infect Stone, who later repeats his signature line and starts her own story, but Kowalski’s nonchalance is clearly only a pose, and an unconvincing one at that, as the actual anxiety behind the casual banter becomes apparent. A later scene underlines the point that his carefree persona is a fraud, an illusion. Surviving in space is a matter of rocket science, as Stone demonstrates when she consults manuals to help her pilot her spacecraft.

Another way people try to handle life in space is to bring along cherished images and objects from Earth, to help make their unusual environment seem more familiar. In this film, photographs of distant loved ones are found everywhere. People continue to play their favorite games; on the ISS, I thought I saw a small floating rook, a chess piece probably used by a Russian crewman, and the Chinese station definitely included a ping pong paddle and ball. Residents of space still want to be consoled and inspired by traditional religions: one panel of the ISS had a card with a medieval painting of Jesus, while a console in the Chinese station featured a small golden Buddha. Most evocative, perhaps, are the quaint reminders of earlier visions of space travel: the ISS is decorated with the famous image of the spaceship hitting the Man in the Moon from Georges Méliès’s Voyage dans la Lune (1902), while a small statue of the Looney Tunes character Marvin the Martian drifts away from the destroyed space shuttle. In reality, of course, there is nothing human-like to be found in outer space, except for the possessions that humans bring with them.

Although the coping mechanisms of humor and homey touches might help people deal with the challenges of space for a while, Cuarón’s film actually appears to recommend another, more drastic solution: to leave outer space forever. True, this is brought about in the film only as the accidental result of a satellite explosion, which destroys a space shuttle, forces the evacuation of humanity’s two space stations, and ultimately destroys them as well. Clearly, though, in the world of this film, no one will be living in space for a long, long time, and while earlier spacesuit films regularly offered stirring rhetoric about humanity’s future endeavors in space, this film says absolutely nothing about any plans to rebuild the stations or to recover from this disaster by launching bold new initiatives to conquer the universe. In fact, since the storm of debris apparently destroyed most of Earth’s satellites, and since the attempted repair of the Hubble Space Telescope which opens the film is never completed, one must assume that even unmanned explorations of the universe will be halted, at least temporarily. It is also telling that while they keep improvising plans to survive, Kowalski and Stone never consider the option of remaining inside a space station and living off its supplies, hoping some future space mission might retrieve them; instead, they focus solely on getting back to Earth, suggesting that this represents the natural option for troubled space travelers. Thus, near the end of the film, when Stone mumbles, “It’s time to go home,” she may be speaking for the entire human race, not merely herself; for if humanity’s hold on space is as tenuous as the film indicates, capable of being ended by one fatal mistake, permanently returning to Earth may represent the best option.

To be sure, actually making an argument against ongoing space travel will invite passionate opposition from some members of the science fiction community, as I once discovered, and I do not wish to revisit that argument here; I am merely suggesting that one can interpret this film as precisely such an argument. If nothing else, this would explain the film’s title, since it really doesn’t seem to be about gravity at all –until the very end of the film, all its events take place in zero gravity. But from the human perspective, what does gravity do? It pulls people back to Earth. And the film’s protagonists, who were scheduled to return to Earth on the next day anyway, constantly feel themselves pulled back to the Earth that they regularly stare at and admire while facing the unending hardships of space. This provides another way to interpret the film’s final dedication: “A mi mama, gracias.” How sweet, one initially thinks; Cuarón is dedicating his film to his mother. Yet Kowalski at one point refers to another mother – “Mother Earth” – so this might also be Cuarón’s way of announcing that the home people should be dedicated to is not space, but Earth. Finally, it cannot be coincidental that a final scene of debris falling to Earth bears an eerie resemblance to films of pieces of the Columbia space shuttle falling toward Texas, commemorating another effort to conquer space that ended catastrophically.

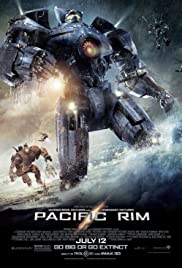

While reviewing Pacific Rim (review here), I suggested that director Guillermo del Toro might have intended to make both the best, and the last, giant monster movie, and perhaps Cuarón was similarly intent upon making the best, and the last, spacesuit film. Certainly, he displays some awareness of previous films in the tradition he is entering: when Stone picks up an oxygen tank so she can use its air to push herself through space, she repeats a maneuver first observed in Destination Moon (1950). A grisly image of a dead astronaut’s face as he floats in space recalls a similar moment in Riders to the Stars (1954), and the film’s scenes of untethered astronauts drifting farther and farther into space recall several earlier films, though the first instance of this trope was in the 1955 British television miniseries Quatermass II. On several occasions, one’s view of a space station or spaceship interior is dominated by a floating pen in the foreground – and a floating pen was the very first image of weightlessness observed in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). The people Cuarón thanked at the end of the film included two directors who contributed to the subgenre, James Cameron (Aliens [1986]) and David Fincher (Alien3 [1992]). And surely, he chose Ed Harris to serve as the voice of Houston’s Mission Control because of the key roles he had played in two spacesuit films, astronaut John Glenn in The Right Stuff (1982) and NASA Flight Director Gene Kranz in Apollo 13 (1995).

Paying tribute to earlier spacesuit films is not particularly difficult, since there are not that many of them; it is always a surprise when another one comes along. And Gravity briefly references one reason for the world’s apparent lack of interest in actual space travel (now evidenced outside of theaters as well, since only the Chinese now seem interested in doing anything other than making money by ferrying tourists into low Earth orbit). When Kowalski is told that the burgeoning debris has destroyed most of America’s satellites, he remarks, “Half of North America just lost their Facebook.” He is well aware, in other words, that nobody in his country is paying any attention to what their astronauts are doing – the important work of repairing the Hubble Space Telescope – or even their suddenly imperiled status; instead, they are completely focused on their online social networks. And there, in a nutshell, is an explanation for the world’s failure to vigorously colonize the Solar System, something that science fiction consistently predicted we would have accomplished long before 2013. Back in the 1950s, the most interesting thing around seemed to be the “new frontier” of outer space, and it seemed inevitable that curiosity about this strange environment would drive humanity to explore its many mysteries. But actual space turned out to be much duller than the space science fiction had promised: no aliens, no habitable environments, no lifeforms – all this space seemed to offer humanity was an icy cold vacuum and lots and lots of rocks. In the meantime, technologies like computers, the internet, and smartphones gave people new ways to explore something that now seemed much more intriguing than outer space: themselves. So, instead of visiting space.com for news about a recently discovered moon of Saturn or plans to capture an asteroid, people log on to Facebook to find out what their old high school friends are doing. And it’s hard to be judgmental about that, because even that obnoxious bully who sat in the last row of Mrs. Johnson’s history class is more interesting than a rock.

Geologists would disagree, to be sure, and if going into space was easy and cheap, the American public would be more than willing to subsidize their space research, and the space research of other scientists. But space travel isn’t easy, as this film emphasizes, and it isn’t cheap either, as the film briefly indicates. For when Kowalski surveys the wreckage of his space shuttle, he makes another portentous joke – “Houston, here’s hoping you have a hell of an insurance policy” – acknowledging that this is not only a humanitarian disaster and scientific disaster, but a financial disaster as well. And this would be another way to summarize the plot of Gravity – the story of how the nations of the world threw hundreds of billions of dollars down the drain by mounting a manned space program that could be ended by a single unfortunate event – and another argument against space travel that is implicit in the film.

In Hollywood, though, the only important financial question raised by a film is: will it make enough money to earn a handsome profit? In striving to achieve that goal, Cuarón enjoys a major advantage, since he was able to complete his film for the relatively low cost of 80 million dollars (surely, the only reason this atypical project was greenlighted), a feat made easier by the economical decision to limit the cast to a total of two actors. (The most puzzling end credit, then, has to be “Greenland Casting”; who did they cast in Greenland? Stunt people? Voices? I mean, they didn’t find Bullock and Clooney in Greenland.) Perhaps, if the film is an enormous success, it might inspire other low-budget spacesuit films, but somehow I doubt it; and Cuarón himself has no such plans, since his upcoming project, A Boy and His Shoe, is described as a realistic children’s film set in Scotland. The director, then, is coming back to Earth, which may also be the fate of both Hollywood and humanity as a whole.

Wonderful review, Gary. My biggest complaint about the film immediately after seeing it was how little time it took to get from the various points A to points B, and how all of humanity’s habitats were conveniently close to one another. Since the action essentially covers little more than 180 minutes, the tension is about escaping this dangerous environment, not adapting to it. If the film had allowed for days or weeks of peril, then finding food and water would have been nearly as important as finding air and fuel. The vehicles are less important as shelter than they are as a means of running away. In that way, it is definitely a departure from many of the stories and the occasional films about the hardships of living in space. The more hopeful of them are about surviving and adapting, not surviving and fleeing for the comfort of the womb. If SF is most often about dealing with change, both in situation and character, this film is more about rejecting change and growth to embrace the seemingly safer status quo of terra firma. If the protagonist completes a journey, it is merely a circular one, though it makes the film no less compelling.

A minor quibble: I believe it was a fire extinguisher that served as a means of propulsion rather than an oxygen tank, which brought immediately to mind the playful extravehicular activity from the movie Wall-E.

Nice review. I believe the Greenland casting is for the voice on the radio. There is a companion short from the other POV that may pop up on the DVD.

Loved this movie. Looking forward to watching it again.

Gary, the debris thing WAS in the film. The one satellite set off a chain reaction destroying a lot of other structures. You must have missed it when you were ogling Sandra’s booty shorts – HA!