Russell Letson reviews C.J. Cherryh

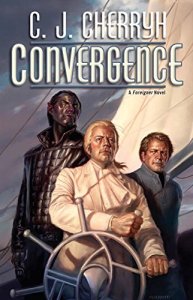

Convergence, C.J. Cherryh (DAW 978-0756409111, $26.00, 324 pp, hc) April 2017. Cover by Todd Lockwood.

By happy accident, as I was working on this column I was also paging through Jo Walton’s excellent collection of retrospective review essays, What Makes This Book So Great, and noted her chapter on ‘‘Re-reading long series,’’ in which she points out not only the pleasures of taking extended rambles through invented worlds, but the structural virtue of developing a narrative space in which ‘‘the books illuminate each other and the longer story… as the series progresses.’’

By happy accident, as I was working on this column I was also paging through Jo Walton’s excellent collection of retrospective review essays, What Makes This Book So Great, and noted her chapter on ‘‘Re-reading long series,’’ in which she points out not only the pleasures of taking extended rambles through invented worlds, but the structural virtue of developing a narrative space in which ‘‘the books illuminate each other and the longer story… as the series progresses.’’

The occasion for Walton’s remarks was C.J. Cherryh’s Foreigner Universe series, which from the publication of its initial volume in 1994 has been chronicling the increasingly complicated interaction of a population of lost-in-space humans and their not-as-human-as-they-appear hosts, the atevi. The 17 previous volumes (arranged in three-book story-arcs) have dealt with alien encounter, interspecies diplomacy, political and bureaucratic maneuvering, palace intrigue, interstellar exploration, revolution and counter-revolution, and multi-species family drama, all punctuated by chases and escapes and shootouts. Up to now, each title ended in ‘‘-er’’ or ‘‘-or’’ (Foreigner, Invader, Inheritor, Precursor, Defender), placing the protagonist’s actions or role at the center, but the 18th book changes that, and naming it Convergence may suggest something about where the series is headed.

Where has the series been for 17 volumes? Readers familiar with the story-so-far can skip this paragraph – though further suggestions and instructions await newcomers on the far side of this necessary expository lump. So. The starship Phoenix gets lost in subspace and emerges near a living world, the planet of the steam-tech-level atevi, who, after a period of lethal misunderstanding, arrange for a human enclave on the large island of Mospheira. The solution to the problems created by incompatible psychologies and cultures takes the form of a single point of contact: the human translator-bureaucrat called the paidhi. After a couple of centuries of slow technology transfer and minimal mutual understanding, a new crisis leads to a difficult but fruitful collaboration between the progressive atevi leader Tabini and the young paidhi Bren Cameron, which in turn leads to great changes in the way the species will share the planet.

Standard advice for those who have not read the earlier books is to go forth and binge-read them in order. They offer pleasures similar to those of the work of, say, Ursula K. Le Guin, Eleanor Arnason, Gwyneth Jones, or Karen Traviss: combinations of adventure in exotic environments, encounters with fascinating Others, and precise observation of social interactions both familiar and novel. And, to echo Walton, like Patrick O’Brian’s 20-volume Aubrey-Maturin roman fleuve, the series follows the career and continuing relationships of its protagonist (and eventually other characters) through so many books that it can offer a variety and range of events and developments not available in a single novel or even a fat trilogy. In fact, since some of those developments are at the heart of the current volume, readers sensitive to the Spoiler Effect should probably go book-hunting now and allow me to address the faithful here assembled.

The title signals not a single agent (a something-er, a doer) but a process – and our understanding of that process is evenly divided between the viewpoints of Bren Cameron and the very young atevi heir-apparent Cajeiri. At the opening, each has a mission that re-immerses him in his own species environment: Cajeiri to continue his acculturation as a future atevi leader, and Bren to encourage a reorientation of humans’ awareness of their position, not only on the Earth of the atevi (now always just called ‘‘Earth’’) but in a stellar neighborhood that includes a powerful spacegoing species, the kyo.

Cajeiri is dispatched to the estate of his culturally conservative but (now) human-tolerant uncle Tatiseigi for a public-relations visit where he will be seen to be engaging in appropriately heir-apparent activities while his father and Tatiseigi manage some inter-clan political business. The trip also will be the occasion for the boy and his young staff to engage with much more senior elements of the Assassin’s Guild that provides security for the aristocracy (and is a potent political force in its own right). Bren returns to Mospheira with a mixed PR-political mission of his own: to get the conservative, self-involved, or merely uninformed factions of the human government to buy into the changes that will be necessary to survive in a suddenly expanded and realigned multi-species environment.

Bren’s half of the story is all political-bureaucratic-procedural and lacking in the kind of strenuous adventure-stuff that usually has him ducking gunfire. Cajeiri, however, does encounter some moderate melodrama when the clan-political issue that was supposed to remain in the background inserts itself into his visit, and he gets close-up involved in the kind of tensions that only atevi social-familial-political arrangements can generate. The generation-spanning secret intrigues that led to the coup and counter-coup that enlivened his father’s administration have left some unexploded ordinance behind, and the boy gets a view into the pathologies and strengths of his people’s management of power. Where Bren’s half of the novel is a demonstration of his competence as a diplomat and a political animal, Cajeiri’s is another chapter in an atevi bildungsroman.

On second thought, even newcomers might find Convergence an engaging (if occasionally puzzling) read – it will not resonate for them as it will for those who remember how uncertain and vulnerable Bren was at the beginning of his career, or how human-hostile Uncle Tatiseigi was before he met human youngsters, or how thoughtless the younger Cajeiri could be when he got restless and went looking for excitement – but the parallel depictions of the two protagonists navigating the complexities of their respective societies, each conditioned by a necessarily partial but passionate understanding of the Other, can stand on its own. (But really, go find the rest of the story. You won’t regret it. If it weren’t for deadlines, I’d follow Jo Walton’s example and re-read the whole cycle from the start.)

–Russell Letson

Read more! This is one of many reviews from recent issues of Locus Magazine. To read more, go here to subscribe.