Paul Di Filippo reviews Lauren Beukes and Bruce Sterling

Slipping: Stories, Essays & Other Writing, by Lauren Beukes (Tachyon 978-1-61696-240-1, 288pp, $15.95, trade paperback) November 2016

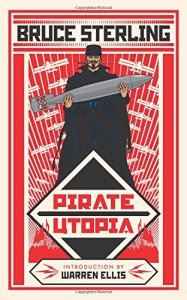

Pirate Utopia, by Bruce Sterling (Tachyon Publications 978-1-61696-236-4, $19.95, 187pp, trade paperback) November 2016

Currently in its twenty-first year of operation, Jacob Weisman’s Tachyon Publications has attained a nigh-legendary stature as one of the leaders and innovators in the modern domain of genre-centric small-presses. Their selections are unfailingly interesting and often end up on award ballots, and the books themselves are handsomely designed. Had Tachyon never existed, the history of our field would be vastly impoverished. We can only hope they continue for a good long time.

Just consider two of their latest offerings to see what I mean.

First, while the Big Five have more or less abandoned story collections, Tachyon continues to promote this essential variety of book. Lauren Beukes’s debut assemblage is a fine example. Coming after four essential novels, the book can only enhance her reputation in the field. Twenty-one stories bulk out the tome, while a handful of non-fiction pieces hang back near the exit. These latter items are entertaining—snippets of journalism, along with some tidbits on the research that preceded Beukes’s novel Zoo City—as well as a touching maternal screed addressed to Beukes’s daughter. But the fiction is really the main attraction here. And since the majority of it appeared first in South African publications, reflecting Beukes’s country of residence, chances are great that the Tachyon audience will not have seen them before.

First, while the Big Five have more or less abandoned story collections, Tachyon continues to promote this essential variety of book. Lauren Beukes’s debut assemblage is a fine example. Coming after four essential novels, the book can only enhance her reputation in the field. Twenty-one stories bulk out the tome, while a handful of non-fiction pieces hang back near the exit. These latter items are entertaining—snippets of journalism, along with some tidbits on the research that preceded Beukes’s novel Zoo City—as well as a touching maternal screed addressed to Beukes’s daughter. But the fiction is really the main attraction here. And since the majority of it appeared first in South African publications, reflecting Beukes’s country of residence, chances are great that the Tachyon audience will not have seen them before.

Just to select and highlight a few favorites.

The book opens with a tiny prose poem “Muse” that sets the vivid and even savage tone of the collection. Creativity hurts, but maybe less so than simple living. Next up is the title story, concerning a cyborg athlete named Pearl Nitseko. The contrast between her humble origins and superstar present are intensely depicted. “The idea of the money sits on her chest.” Tactile and colorful, those are keys to Beukes’s style.

“Princess” is a wry modern fairy tale about the awakening of one of the Beautiful People who populate celebrity wet dreams.

The princess and the handmaid fled the bright and terrible city. They bought a farm in the mountains of Ecuador and launched a trendy fashion label of hypoallergenic alpaca wool products in couture cuts.

The handmaid still struggled with the princess from time to time; people aren’t readily cured of a lifetime of bad habits, not even by fairy-tale miracles. She found the alpacas to be generally sweeter of temperament, although when riled, they would spit a sour green slobber of saliva and stomach acid and half-dissolved grass. And at least, in her experience, the princess had never done that.

“Parking” follows the Walter-Mitty-style life of a traffic cop, but is more tragic than otherwise. Beukes’s intermittent focus on mimetic settings such as here reflects a groundedness in reality that even her SF shares.

Reminding me a bit of Lucius Shepard’s Green Eyes, “The Green” concerns a corporate expedition to an alien world where corpses are reanimated by a native slime mold. Our protagonist eventually choses to succumb to a queasy fate. “Unathi Battles the Black Hairballs” is pure kaiju-mecha madness amped up to eleven. “The creature resembled a toothsome Godzilla-sized hairball studded with gnashing sharky mouths…”

“Unaccounted,” a tale of interstellar warfare, has this killer closing line: “You can’t dehumanize something that isn’t human.” And finally, my absolute favorite selection: “Ghost Girl,” which chronicles the interactions between a teen Goth Girl spirit and a male student of architecture in a manner that brings to mind Peter Beagle filtered through comedian Margaret Cho.

Beukes writes with passion and a hot immediacy, employing demotic prose that often attains a gritty poetry. She favors capturing the explosive instant rather than the multi-linked chain of circumstances that constitute most stories. This trait lends her work intensity and impact, but detracts a bit from any sense of grand patterns enacted and long-term destinies fulfilled. Luckily, her longer fiction remedies this deficit quite handily, making the total Beukes canon into a well-balanced sculpture.

All unwittingly, I have been preparing myself by a certain course of study to truly appreciate Bruce Sterling’s outrageous and droll new novella, Pirate Utopia, set in a counterfactual version of the Adriatic city of Fiume—or as it is dubbed in the book, the Regency of Carnaro. My preparatory work consists of reading Rebecca West’s Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey Through Yugoslavia. This mammoth, elegantly written survey of Balkan history and current (1941) conditions in the region is a chronicle of high heroism, mad idealism, craven duplicity, dashed nobility, peasant endurance, treachery, faith, desperate inventions, religious fervor, centuries-long subjugation, and fiery revenge. To say that Pirate Utopia captures the same set of values, virtues, vices and vicissitudes is merely to affirm that both West and Sterling are working from intimate acquaintance with the region’s realities. Sterling adds in a couple of other narrative tributaries—the pulp tradition of larger-than-life adventurers, and the tradition of Italian Futurism—but basically he and West are soul mates.

All unwittingly, I have been preparing myself by a certain course of study to truly appreciate Bruce Sterling’s outrageous and droll new novella, Pirate Utopia, set in a counterfactual version of the Adriatic city of Fiume—or as it is dubbed in the book, the Regency of Carnaro. My preparatory work consists of reading Rebecca West’s Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey Through Yugoslavia. This mammoth, elegantly written survey of Balkan history and current (1941) conditions in the region is a chronicle of high heroism, mad idealism, craven duplicity, dashed nobility, peasant endurance, treachery, faith, desperate inventions, religious fervor, centuries-long subjugation, and fiery revenge. To say that Pirate Utopia captures the same set of values, virtues, vices and vicissitudes is merely to affirm that both West and Sterling are working from intimate acquaintance with the region’s realities. Sterling adds in a couple of other narrative tributaries—the pulp tradition of larger-than-life adventurers, and the tradition of Italian Futurism—but basically he and West are soul mates.

But you, as a savvy reader of fantastika, need know nothing special about the region to relish Sterling’s bravura performance. In the deft manner of the Grand Master speculative fictionist that he is, he provides all the background info and context necessary. (Some copious and generous ancillary material at the rear of the book illuminates the affair even more deeply, if you wish to investigate.)

Chapter One plunges us in media res into the Fiume scene circa early 1920. (The whole timeframe is merely a few months in that year.) In the aftermath of WWI, the city has been taken over by a band of idealists, rogues and chancers, all of them exhibiting a heady mix of motives and desires, not all of which derive from the saner precincts of their teeming brains. “The Regency of Carnaro was a clique of armed, dissolute poets who robbed bankers, then distributed the means of production to labor unions.” Our main viewpoint character is one Lorenzo Secondari, “the Pirate Engineer.” All of twenty-four-years old, Secondari is a hardened military veteran intent on transforming the staid world of the bourgeois and the powerful into a kind of techno-anarchist dreamland, fit for the ubermensch. Mostly this involves producing cheap handguns and aerial torpedoes. When Secondari is recruited into the actual government of Fiume— such as it is—as Weapons Minister, under the Prophet, Gabriele D’Annunzio, he is empowered to make his dreams come true.

We careen amongst the colorful players, both real and imagined, as they ride the wild tiger of their fantasies. The language is deadpan, the dialogue declamatory. Then, when the Americans come calling—in the form of an official delegation consisting of Harry Houdini, H. P. Lovecraft, and Robert E. Howard—Secondari finds new awesome horizons beckoning.

Ultimately, I would call this book Sterling’s Pynchon homage. This whole text could almost be wedged sidewise into Gravity’s Rainbow without disturbing the Pynchon flow. And the motley cast in Fiume recalls “Benny Profane and the Whole Sick Crew” from V.. But Sterling is no mere Pynchon-wannabe. His voice offers a unique timbre that blends the coolly intellectual Fabianism of Wells with the gonzo absurdity of the Spider pulps. This is Fritz Lang directing Buckaroo Banzai.

Despite its solid anchorage in the events and attitudes of the 1920s, however transmogrified, this book speaks to similar circumstances in other eras. We hear the speeches of Occupy Wall Street and the Ninety-nine Percenters when Secondari preaches that the pirates should “Kill the ruling class! Erase them! Liquidate them without pity. Build the new world on their bones. It’s the only way to make anything that’s fresh and clean!” And we are surely mean to think of the Age of Aquarius when Secondari inveighs against too much emphasis on “lifting the skirts of pretty girls, after we give them votes, and hashish, and jazz records!” Hippy heaven indeed!

Sterling’s primal message, I think, is that all these affiliated interstitial pockets of chaos and liberation are forever fleeting and temporary, and must be enjoyed while they flourish, for however brief a span.

Lastly, I have to marvel at the superbly gorgeous design and illustration work by the legendary John Coulthart, who conjures up the esthetics of this period with a 21st-century overlay. His artwork makes this volume a fine instance of Tachyon’s dedication to the field.