Gary K. Wolfe reviews Lisa Goldstein

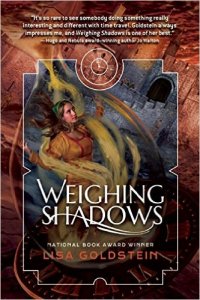

Weighing Shadows, Lisa Goldstein (Night Shade 978-1-59780-840-8, $15.99, 318pp, tp) November 2015.

I’ve long contended that Lisa Goldstein is one of the more underappreciated of modern American fantasists, from her award-winning Holocaust novel The Red Magician, to her Borgesian Amaz stories and the novel Tourists, to her revisiting classic Grimm materials in 2011’s The Uncertain Places, her most recent novel until Weighing Shadows. But Weighing Shadows marks a departure from her usual fantasy themes, moving into a combination of time-travel adventure (which she previously explored in The Dream Years) and contemporary conspiracy thriller, with a growing undertone of feminist utopianism, which turns out to be the among most interesting aspects of the book.

I’ve long contended that Lisa Goldstein is one of the more underappreciated of modern American fantasists, from her award-winning Holocaust novel The Red Magician, to her Borgesian Amaz stories and the novel Tourists, to her revisiting classic Grimm materials in 2011’s The Uncertain Places, her most recent novel until Weighing Shadows. But Weighing Shadows marks a departure from her usual fantasy themes, moving into a combination of time-travel adventure (which she previously explored in The Dream Years) and contemporary conspiracy thriller, with a growing undertone of feminist utopianism, which turns out to be the among most interesting aspects of the book.

Ann Decker is a not-very-successful computer tech and part-time hacker who finds herself recruited, for reasons she and the other recruits can’t initially fathom, by a shady corporation called Transformations, Incorporated, which turns out to be in the time travel business. Unlike Kage Baker’s Company or Connie Willis’s Oxford historians, they claim to be about improving the past, through apparently trivial assignments – ‘‘move a vase from one room to another, or keep someone from getting to work on time.’’ Their improbably precise cause-effect algorithms, which make Asimov’s psychohistory about as unsophisticated as playing the ponies, have calculated that such strategically placed alterations will help ameliorate the catastrophic future that lies in wait – from which the Transformations people themselves claim to come.

Needless to say, it doesn’t take long for Ann and her fellow recruits to begin suspecting the real purposes of Transformations, and these doubts become more clearly focused after they encounter a seemingly renegade time traveler named Meret. Ann’s first assignment takes her to ancient Crete, and it goes badly: one of the team members is killed, and when they try to make contact with a leader called Minos, they learn that he’s merely a minor functionary. The next trip, though, takes her to Alexandria, where she meets the legendary teacher Hypatia, and the conversations they have amount to one of the high points of the novel, reminiscent somewhat of Jo Walton’s philosophical/historical thought experiments in her Just City series. Still later she finds herself in a village in southern France in the 13th century, where a local religious sect, regarded as heretical, becomes a target of Crusaders. Throughout, Ann learns more about Meret, about the company, and about a mysterious sect of women called the sisters of Kore, who seem to have their own plans about the future.

Although Goldstein seems to have done her research, she doesn’t spend much time on creating a deeply textured portrait of these past societies; everyone she meets talks in what sounds like contemporary English (Ann and her colleagues seem to have remarkable facility in learning archaic languages and dialects), and when their host in ancient Crete ‘‘took platters of food out to the table,’’ we can’t help but wonder what that food is, exactly, though we’re told there’s a smell of fish. Similarly, Hypatia – the most compelling historical figure in the novel – speaks almost like a 20th-century soulmate. But once the novel establishes its major theme, which is the relationship of individual action to historical forces, both the historical-novel details and the corporate thriller plot (something Goldstein doesn’t seem particularly comfortable with or interested in) fade into the background, and Ann’s final, almost quixotic search to find the remnants of her ancient adventures in her own world becomes a genuinely moving quest for identity and empowerment.