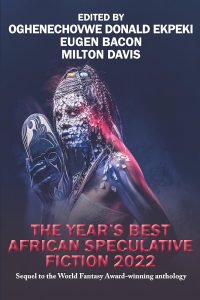

Niall Harrison Reviews The Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction 2022 edited by Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki, Eugen Bacon & Milton Davis

The Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction 2022, Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki, Eugen Bacon & Milton Davis, eds. (Caezik/OD Ekpeki Presents, 978-1-64710-077-3, $11.49, 450pp, eb) December 2023.

The Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction 2022, Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki, Eugen Bacon & Milton Davis, eds. (Caezik/OD Ekpeki Presents, 978-1-64710-077-3, $11.49, 450pp, eb) December 2023.

The Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction 2022 opens with WC Dunlap’s “March Magic”, a brief story about a critical day in twentieth-century American history. It is 28 August 1963, the day of the March on Washington, and Mama Willow, a swamp witch – “Black, Native, woman… leading my children to safety” – is calling a gathering. From the North comes the Salem Witch; from the East, the Root Woman; from the South, “my Mambo”; and from the West, the Preacher’s Daughter. They are joined by “five young Black men dressed in crisp dark suits,” sent to provide protection. They perform a blood magic and send a message into Martin Luther King, Jr.’s ear: “Tell ’em about the dream!” He does.

The story is effective, both as a metaphorical affirmation of the role of Black women in US civil rights struggles, and as a statement about the kind of anthology the reader is entering. No other orientation is provided: there is no editorial introduction or commentary in the book, which I at least felt was a shame. Traditionally, year’s best volumes attempt to represent a community at a moment in time, and I think they are most valuable to readers when both the methodology and the vision of the editors are explicit. A blog post from Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki announcing this volume answers some of my questions, but not others. Eugen Bacon and Milton Davis are introduced as “guest editors” (but how they divided the work is not stated); this edition is intended to “pay special attention to black speculative poetry and the power of the word” (notable given that the first volume did not include poetry; but whether the editors had different remits for fiction and poetry is unclear, and relevant given that the book includes stories by all three editors, and poetry by Bacon as well); and the series as a whole “aims to draw attention to the works of Africans and people of African descent.” I think a more complete framing within the book would only have made it stronger.

Nevertheless, what seems clear to me from the final selection is that the 24 stories and 15 poems from 32 different writers aspire to present the broadest possible definition of “African,” one not restricted by race, geography, or subject matter. Establishing the precise demographics is a little challenging, because the book also doesn’t include contributor biographies, but by my estimate a little over a third of the contributors are from the United States, and among the rest at least ten different African nations are represented, plus (usually as part of some hyphenate-identity) Jamaica, Canada, Australia, Germany, and the UK. So, I take Dunlap’s story, in this context, as a de facto introductory statement: an affirmation of African influence within US history and, by extension, throughout the world.

So it’s not a surprise when other stories open in Memphis (Sheree Renée Thomas’s lynching-revenge story “Barefoot and Midnight”) or drowned Baltimore (Donovan Hall’s posthuman adventure story, with giant crab, “A Sunken Memory”); or travel to the moon (Nick Wood’s PTSD exploration, “A Pall of Moondust”) or beyond (T.L. Huchu’s military-SF “The Mercy of the Sandsea”). Nalo Hopkinson’s Sturgeon Award-winning “Broad Dutty Water: A Sunken Story” takes place in a future drowned Caribbean, embedded in a global context of “refugees, misery, sickness everywhere,” yet manages to find a strand of hope, a new thing that might mean people can stop treading water and start building again. Every sentence is rich with cultural, technological, and character detail; it seemed to me to be the most complete story in the anthology.

The heart of the book, however, and most of the other best stories, centre continental Africa. Chịkọdịlị Emelụmadụ’s “How We Are” is set largely in and around markets such as Eke Awka in Southern Nigeria. The narrator has the unwelcome ability to make living things sicken, and runs a scam with her grandmother, providing diagnoses for ailments that the customers didn’t originally have, and then selling them cures. The sensory experience of the market is vividly described, as are the narrator’s feelings when she meets and falls in love with another woman; a final turn into horror is brilliantly managed. “A Soul of Small Places” by Mame Bougouma Diene and Woppa Diallo is another dark piece, and already the winner of the 2023 Caine Prize for African Writing. In rural Senegal, the narrator and her sister hurry to and from school, in fear of assault and rape by local men; a supernatural catharsis does not erase the pervasive unease of the story’s opening scenes.

Perhaps the most exciting works in the book are the two stories by Tlotlo Tsamaase. Both “Peeling Time (Deluxe Edition)” and “District to Cervix: The Time Before We Were Born” are furious deconstructions of gendered power dynamics. In the former story, a musician finds that his trauma has become a real and animate thing, something that enables him to steal the dreams of others – of women – and shape them into music. In the latter, “soul-tech” (“a fusion of science and muti”) has meant that not only is reincarnation an established fact, but that people can choose the body they will be reborn into – to me, the most compelling science fictional exploration of a concern that recurs throughout the anthology, the power of ancestry and lineage. A debate over inheritance becomes a pre-birth power struggle between siblings. Both stories are somewhat raw, revelling in linguistic possibility – “the power of the word,” as Ekpeki’s blog had it – more than precision. Take the following sentence from “District to Cervix”, describing the realm in which souls find themselves waiting to be reincarnated: “The dull sun screeches time against the backbone of the present.” I can’t tell you exactly what that means, except that it clearly means something is desperately wrong and needs to be fixed, and that sense of urgency brought both of Tsamaase’s stories to life for me.

Unfortunately, I didn’t feel as much urgency or liveliness elsewhere in the anthology as I want to in a Year’s Best. Editors Ekpeki, Bacon & Davis are to be commended for casting a wide net – the included works come from 20 different venues – and they’ve found a few gems, such as “District to Cervix”, which appeared in Prisms, a limited-edition hardcover anthology from PS Publishing, that probably will not have been seen by many readers, and deserve to be. The stories by Ugochi Agoawike, Nnamdi Anyadu, and Tobi Ogundiran also fall into this category, and the selection of poetry is welcome; I particularly liked the two by Akua Lezli Hope. But much of the rest seemed to me routine work. On balance, for a single-volume sampling of recent African SF, I find it easier to recommend Ekpeki’s recent volume Africa Risen, co-edited with Zelda Knight and Sheree Renée Thomas, which includes the Dunlap and Diene/Diallo stories, and Tsamaase’s “Peeling Time”, and a lot of other strong stories besides.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS REVIEW, please take a moment to support what we do! Our annual fund drive ends April 5. We must meet our funding goals to continue!

In Niall Harrison’s spare time, he writes reviews and essays about sf. He is a former editor of Vector (2006-2010) and Strange Horizons (2010-2017), as well as a former Arthur C. Clarke Award judge and various other things.

This review and more like it in the February 2024 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.