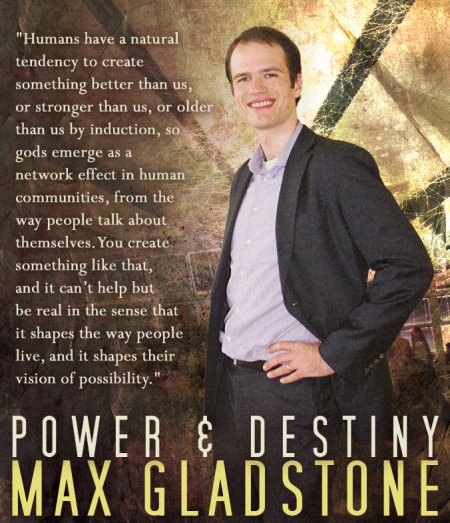

Max Gladstone: Power & Destiny

Max Walker Gladstone was born May 28, 1984 in Concord MA, and grew up mostly in Ohio and Tennessee. He graduated from Yale University, where he studied Chinese. He has been to China several times, and lived there from 2006-8 as a Yale-China Fellow, teaching in a rural school.

Debut novel Three Parts Dead (2012) began the Craft sequence, ‘‘tales of wizards in pinstriped suits and gods with shareholders’ committees,’’ which continues in Two Serpents Rise (2013), Full Fathom Five (2014), and Last First Snow, forthcoming July 2015. Gladstone was a finalist for the Campbell Award for best new writer in 2013 and 2014. He also writes games, notably interactive fiction Choice of the Deathless, and has a Pathfinder Tales RPG tie-in novel forthcoming in 2016.

Gladstone lives in Somerville MA with his wife, Stephanie Neely.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘The idea that led to me writing Three Parts Dead was a Big Idea. It was really an interpretive lens I created to write about issues in the world economy. I came back from China in 2008. I was looking for work at the same time the whole economy tripped and stumbled into a wood chipper. I was impressed by the terror that reverberated through the markets, the fear you could see in news anchors’ eyes and hear in the voices of the guests they brought on to explain what had happened – to the extent that anyone could describe what happened – and the religious dimensions of it. Hundreds of billions of dollars of damage, trillions. The world teetering… but nothing had happened on a physical level. There was no smoking crater that was AIG. ‘This once was the castle of my father’ – there was none of that. The economic crisis was a cataclysm on a spiritual level that nevertheless had real physical effects on human beings. It was like gods dying. Like Ragnarok, or Gotterdammerung at least. We were witnessing the twilight of a certain set of gods and monsters, which then devoured their own entrails and gave birth to another set of god/monsters, which is what always happens with gods. Money, and law, and the change of world systems were easy for me to model in the context of fantasy. I could talk about this stuff with magic: in fact, it was easiest to talk about it with magic.

‘‘Those experiences dovetailed with things my wife talked about (she was in law school at the time) and things her mother talked about (she’s a bankruptcy lawyer), about the way bankruptcy law works. Growing up in the middle of nowhere in Tennessee, I thought bankruptcy was, ‘Well, we have no money anymore, so we’re just going to fire everybody and sell our stuff and try to pay everyone back.’ The notion that the bankrupt entity could be rescued, in some horribly invasive way, didn’t occur to me. Bailing out a corporation – a notional fictional entity – seemed a lot like taking a real dead person, putting them on a slab, surrounding them with certain protections and guards, consulting with others who have an interest in the dead entity, taking the parts that were left, wiring them all together with silver and cold iron, hooking the body up to a lightning rod, and telling Igor to crank away. All of a sudden, the corpse of Delta Airlines rises from the table, groaning: ‘Flights will come.’

‘‘I realized how much my wife’s law school classes sounded like things you’d study at Hogwarts. Most of the time when you go to graduate school the courses are ‘Advanced Theories’ and ‘Topics in Confrontational Microbiology’ or something. In law school, you find titles like ‘Remedies,’ and ‘Contracts,’ and ‘Corps.’ Corporations gets called ‘corps,’ pronounced like ‘corpse,’ as in, ‘I have to go to my corps class.’ I had this post-industrial fantasy world taking shape in my head, as a dark mirror of everything going on around me and in the world economy. With Three Parts Dead I sat down to write a story that was a little contained, because I couldn’t tackle the global catastrophe entirely. I could cover the aftermath, a contained version of it, which is very much what’s going on in Three Parts Dead: the god of the city has died. It’s more like the last few years of Detroit than the financial catastrophe of 2008.

“…The philosopher Feuerbach had this idea that God is a projection of human potential. Humans have a natural tendency to create something better than us, or stronger than us, or older than us by induction, so gods emerge as a network effect in human communities, from the way people talk about themselves. You create something like that, and it can’t help but be real in the sense that it shapes the way people live, and it shapes their vision of possibility. I’m always in conversation with these questions of power and destiny and possibilities.”

…

‘‘There’s an illusion that there’s such a thing as pure ‘literary fiction.’ I say that in the largest quotes possible because I don’t think it corresponds with literature about the real world. We have stories about middle-class, comfortable people problems, and we tell ourselves that’s what the world is. That’s the circle of firelight. That’s the tiny little raft. There are oceans and oceans beneath it.

‘‘I wanted to write individual books. Terry Pratchett was an enormous influence on me growing up. Any given Terry Pratchett book, you could pick it up and read it easily, assuming you have a little of that skill people acquire in genre fiction of dropping into a world and orienting yourself. You could pick up any book in the Discworld series, anything off the shelf, and know where you were in about 40 pages. By the end of that book you would have a complete story told to you. There would be more aspects of these people and this world that you could continue to explore, but it wasn’t necessary. That was amazing. That approach felt very satisfying to me as an alternative to the ‘seven doorstoppers and no ending in sight’ approach, which has its own advantages, of course. Still, I felt very strongly about wanting to write complete stories in each book.”

…

‘‘The stories that influenced me were stories we would consider genre. You try to tell anything like Journey to the West in terms of its blocking or structure, and it’s automatically genre. At the same time, I was growing up with SF. When my uncle Danny found out I was interested in Star Trek, he showed up with a cardboard box full of Ace paperbacks and a little Post-It note listing every book that had won both the Hugo and Nebula Awards up to that point. He said, ‘Read these first. Start with these Asimovs here because you’ll need them to understand what else is going on.’ That was my introduction to genre. It was amazing. I read Foundation. I found Roger Zelazny and read Lord of Light for the first time when I was ten, and didn’t understand it at all. Then I read it when I was 11 and understood a little. I grew up with that book, though. When I was 14 I realized how funny it was, on the first page even, with Yama messing with the dials on the prayer machine and invoking the local fertility gods by their most prominent aspect – I laughed so hard when I figured out what that actually meant. I realized how much humor was in the text, just slightly submerged.”

Read the complete interview in the July 2015 issue of Locus Magazine. Interview design by Francesca Myman.