Russell Letson Reviews The Soldier by Neal Asher

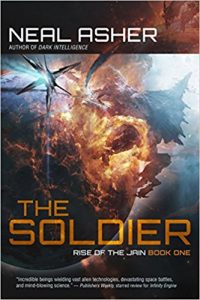

The Soldier, Neal Asher (Night Shade 978-1-59780-943-6, $26.99, 375 pp, hc) May 2018. Cover by Adam Burn

The Soldier, Neal Asher (Night Shade 978-1-59780-943-6, $26.99, 375 pp, hc) May 2018. Cover by Adam Burn

Neal Asher keeps extending his already sprawling Polity setting, devising ever more dire and dangerous scenarios and filling in a deep history characterized by predation, warfare, genocide, extinctions, and the apparent impossibility of getting rid of any threat (or extinct species) permanently. One of the most persistent and destructive features of this universe is the ancient, seductive, deadly, totipotent Jain technology that figures prominently in the earlier Agent Cormac sequence. This disease-like technology is so powerful as to appear magical, and in a less relentlessly materialistic imaginary world it well could be. But as outrageously gaudy, mysterious, and transformative as Jain enhancements and weaponry are, Asher relentlessly insists that they are rooted in the material nature of things – even if that nature includes access to the U-space universe where the rules are very different from those of our home cosmos.

But I get ahead of myself. The Soldier: Rise of the Jain Book One opens a new set of chapters in the story of the infiltration of Jain technology into the Polity/Prador neighborhood. The story hosts a reunion of characters from earlier books: the Jain-taming haiman (AI-enhanced human) Orlandine; the Jain-spreading creature once called the Legate, now Angel; and one of the ancient, moon-sized, enigma-loving aliens called Dragon. New characters include familiar Asherian types: a couple of Hoopers, nearly-indestructible humans from the everything-eats-everything planet Spatterjay; some disturbingly upgraded and cooperative (if still vicious) Prador; and miscellaneous snarky battle drones and AI warships. They are joined by some even stranger creatures, often singletons of various kinds: relicts and lone survivors, the creation of a rogue AI warship, self-redesigned cyborgian entities.

As usual, some of these beings are on (or over) the edge of craziness, or otherwise mentally infiltrated, enslaved, or absorbed. The bored weapons-platform AI Pragus amuses itself by resurrecting an ancient life form only to find itself subverted by it. Trike, a relatively young Hooper, struggles with a mad rage that manifests as, among other things, some nasty physical traits of Spatterjay lifeforms. Angel has taken mental control of Trike’s wife, but in turn harbors an entity that compels him to seek out a particular Jain artifact. These enslavements and transformations drive much of the plot, as antagonists become tools or even unwilling allies.

The McGuffin and eventual apex antagonist of the novel is a Jain supersoldier, discovered and resurrected millions of years after the vanishing of the civilization that created it and the rest of its deadly cousins. Some of those cousins are concentrated in an accretion disk around a dead star, guarded by a swarm of weapons platforms and war drones overseen by Orlandine, whose official, Polity-sanctioned job is to prevent Jain tech from breaking out and opportunistic thieves from breaking in. Her unofficial project is something much larger and considerably more hazardous.

Other actors are also interested in the Jain soldier, whether they want to deploy or destroy it, and once the thing is activated it has an agenda of its own. Nor is the soldier the only object of desire – just about everybody in the cast wants something, whether the return of a loved one, or payback, or an artifact (or lots of artifacts), or just peace of mind. Thus the plot is complicated and multi-threaded as various Polity and Prador operatives, freelance crooks, grotesques, obsessives, revengers, and mad-scientist analogues kidnap, subvert, waylay, scheme, lie, and steal, with the whole set of pursuits punctuated by outbreaks of violence ranging from nasty and personal to landscape-rearranging or planetoid-destroying battles.

For all the Doc Smithian space operatics and Jacobean revenge-melodramatics, though, what I find most intriguing are the large chunks of back-story extending far into the deep history of the galaxy, a Stapledonian tale of eternal conflict-to-the-point-of-genocidal-extinction. The most intriguing chunk, of course, traces the origin of the Jain – “not a society, not a polity, not a kingdom, but a perpetual war” – and connects it to the novel’s present and its future, if any.

I had thought with the Transformation trilogy (Dark Intelligence, War Factory, Infinity Engine) that Asher had maxed out what could be done with the Polity setting – that the near-metaphysical implications of the fate of Penny Royal constituted a kind of narrative event horizon. I think I might have been mistaken.

Russell Letson, Contributing Editor, is a not-quite-retired freelance writer living in St. Cloud, Minnesota. He has been loitering around the SF world since childhood and been writing about it since his long-ago grad school days. In between, he published a good bit of business-technology and music journalism. He is still working on a book about Hawaiian slack key guitar.

This review and more like it in the May 2018 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.