Death and Other Speculative Fictions by Caroline Hagood: Review by Jake Casella Brookins

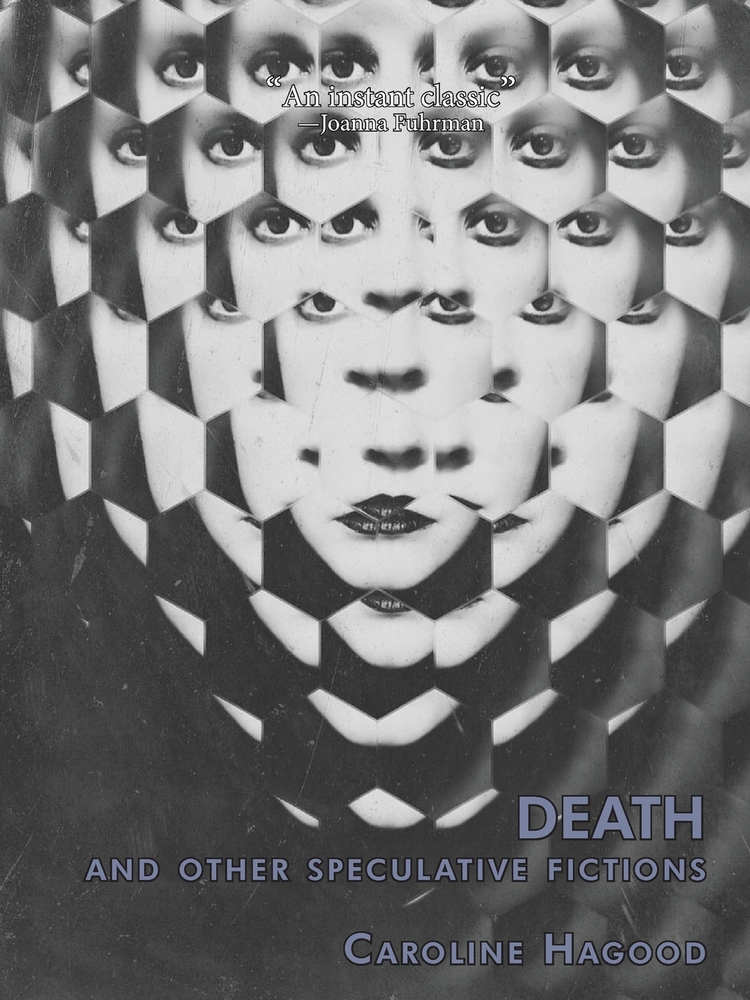

Death and Other Speculative Fictions, Caroline Hagood (Spuyten Duvvil 9781963908503, $18.00, 116pp, tp) January 2025.

Death and Other Speculative Fictions, Caroline Hagood (Spuyten Duvvil 9781963908503, $18.00, 116pp, tp) January 2025.

Caroline Hagood’s Death and Other Speculative Fictions is an astonishing read, comforting and discomforting in equal measure. A philosophical, poetic meditation on the death of a parent, it’s a whirl of reflections on what fantastic stories can say about death, and vice versa. Don’t be dismayed by the fact that this doesn’t look like a standard SF text – it’s energetic, elegiac, and insightful, using science fiction works and ideas to think through an intense personal experience.

So, what is this book? It’s subtitled “An Essay in Prose Poems”. And I have to be honest: I absolutely adore this format. There are 93 single-page prose poems, separated into three sections. Dense with allusions, occasionally dreamlike or portentous, they remain largely conversational in tone; Hagood crafts a remarkable, sometimes unruly synthesis of voice and image such that Death and Other Speculative Fictions has almost a dual tempo. It’s a page-turner: an engaging speaker, a rich brew of ideas and references that carry you naturally along. And yet also a slow book, a halting book – it halts the reader, as poetry can, with the inertia of its emotional substance. At rest, and in motion. I know I burned through this in a single sitting, but at the same time I have the memory, and I know it’s accurate, of putting the book down after every entry, staring out the window, processing.

Structurally, the book circles its subject matter and lays out its approach (“Death as the Ulysses of Desperate Housewives”), then dives into a more granular memory of the father’s death (“Death as the Beginning of Dracula”) before surfacing with the contemplative and integrative final section (“Death as Furiosa”). Its use of speculative devices to react to grief, to think through it, is present from the very first entry: “When they all asked if there was anything they could do, I requested a time machine.” SF imagery and authors – Hopkinson, Stoker, Jemisin, Bradbury, Adeyemi, and more – serve as ghosts and guideposts, if not quite a Greek chorus then at least a comforting refrain or a set of unexpected bridges. One of the things that Hagood flags early is the idea that “the history of writing is the history of grappling with death.” And it certainly is, back to Gilgamesh, but I rarely see science fiction so seriously connected with such a serious topic. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and Blade Runner (Scott and Villeneuve flavors) make repeated appearances, with their fixations on ephemerality and persistence, and the final section of the book draws something sustaining from Mad Max: Fury Road, something about how it shouts “life” from all its death and mayhem.

And I should make it clear that the book is, like Miller’s movies, intensely lively despite the centrality of death; there’s a vividness and energy to these prose poems that complements and counterbalances their sadness. Even in the brutally, bodily real middle section, with its details of decline and mundane hospital horrors, there are flashes of fantasy, moments of clarity, startling sequences of estrangement and wonder. Again that doubling: grounded, physical, serious; but partaking of the numinous, magical, silly possibilities of science fiction and fantasy. I don’t know if you’ve experienced the way that hypervigilance and the surreal can crash into each other in intense moments and our recollections of them, but there’s an amazing sequence here, a cab ride to the hospital, that captures how reality warps right when it seems you’re the closest to it you’ve ever been.

Speculative fiction folks should seek this out – it does a lovely job of theorizing what SF is, that it lets us “really see how things are here on Earth, and how they need to change,” and it ties the genre to death in a way I’d never thought of before, which I think will affect my future reading: “it turns out that not only dragon stories but all scientific, philosophical, and religious theories about what happens after we die have been speculative fictions all along.” I think that’s a reference to Tolkien’s The Monsters and the Critics, there; elsewhere, Hagood takes up Vonnegut’s Tralfamadorians and “The Body” from Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and a myriad of other texts, to come at loss from different angles.

Grief, loss – these are intensely real, shaking, serious matters, so much more solid than our make-believe and flights of fancy. And yet, of course: speculative fiction, like any literature, like any art we admire and devote some portion of our lives to – it is a part of us. We should not be shocked or shamed to find it is a part of our grief, as well – and a part made of words, of images, concerned with big ideas and impossible imaginings. The way Hagood uses science fiction to talk about, to think about, so big and outlandish and impossible a topic as death is genuinely moving. Reading Death and Other Speculative Fictions changed how I look at some of the books on my shelves, some of the deaths in my life: a new feeling for what some of these stories are, what they can do, what they cannot. Highly recommended.

Interested in this title? Your purchase through the links below brings us a small amount of affiliate income and helps us keep doing all the reviews you love to read!

Jake Casella Brookins is from the Pennsylvania Appalachians, and spent a fantastic amount of time in the woods. He studied biology, before switching over to philosophy & literature, at Mansfield University. He’s been a specialty coffee professional since 2006. He’s worn a lot of coffee hats. He worked in Upstate New York and Ontario for about 8 years. He’s been in Chicago since 2013; prior to the pandemic, he worked for Intelligentsia Coffee in the Loop. Starting in 2021, he’s been selling books at a local indie bookstore. He lives with his wife, Alison, and their dogs Tiptree & Jo, in Logan Square.

This review and more like it in the February 2025 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.