The Tomb of Dragons by Katherine Addison: Review by Liz Bourke

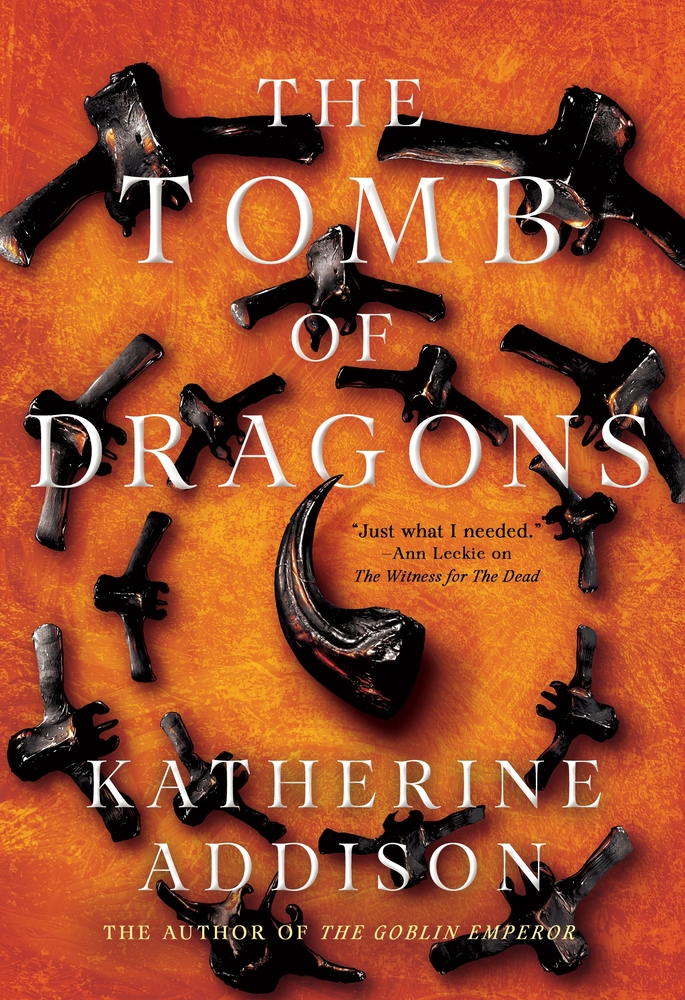

The Tomb of Dragons, Katherine Addison (Tor 978-1-250-81619-1, $28.99, 352pp, hc) March 2025. Cover by Chris Gibbs.

The Tomb of Dragons, Katherine Addison (Tor 978-1-250-81619-1, $28.99, 352pp, hc) March 2025. Cover by Chris Gibbs.

It is impossible for me to overstate how much I enjoy the novels of Katherine Addison set in the world of The Goblin Emperor. Their only real competition, for me, is the ‘‘World of the Five Gods’’ continuity of Lois McMaster Bujold: the sense of being in the hands of a master, the breadth and depth of world, the unflinching eye for human nature paired with a deep well of compassion and a lingering sense of the numinous. Addison’s latest, The Tomb of Dragons, is the third and for now final volume in the ‘‘Cemeteries of Amalo’’ sequence.

The three books that comprise the ‘‘Cemeteries of Amalo’’ series to date – The Witness for the Dead, The Grief of Stones, and now The Tomb of Dragons – are unconventional mysteries. The narrator and main character is Thara Celehar, who is a formerly disgraced prelate of Ulis (a god concerned with matters to do with the dead) and a Witness for the Dead. The novels to date have wrestled as much with Celehar’s loneliness, his grief and sense of self-worth, his spiritual journey, and his place in the world, as much as with the conventions of a mystery novel that requires mysteries to be solved.

Celehar’s duty and calling is to, when petitioned, stand for and represent a dead person: sometimes, to pursue justice on their behalf. Witnesses for the Dead have a spiritual gift that allows them, under certain circumstances, to hear the dead. Celehar has lost that gift, at the beginning of The Tomb of Dragons, and fears that along with it he has lost his calling, any sense of certainty about his life, and also his income – as the small stipend allowed to him as the city of Amalo’s official Witness for the Dead will end along with his role.

A small commission from the Archprelate of Ulis offers some respite, and a healer holds out some hope for the return of his gift, but a set of unpleasant misadventures sees Celehar abandoned down the mine known as the Tomb of the Dragons: a mass grave, site of the murder of nearly two hundred thinking, speaking beings by the Clenverada Mining Company several generations ago. The circumstances that permit him to escape the mining find him with an unprecedented commission: to stand as Witness for all those dead dragons, and pursue restitution on their behalf. Unfortunately, the Clenverada are powerful, deeply entwined with the workings of the empire, and not inclined to suffer Celehar tilting at windmills when they can simply have him killed. For Celehar’s part, his only chance to fulfil his task and properly Witness for the dead dragons is to appeal to the emperor. The emperor will hear him. But first he must survive to reach the imperial court, and afterwards, he must survive to return.

Though Celehar isn’t the kind of man who realises it easily, he has friends and acquaintances who value him deeply. (Celehar is long past the point where humility becomes self-harm. One of the themes of the series has been his discomfort with other people valuing him for himself, with friendship and connection. He has an awkward certainty that he is more a bother than a blessing: a very relatable trait, but one that makes him a man given more to grief than to joy. That his calling is so much among the dead and the bereaved gives that grief an even sharper point.) One of those who values him is the emperor himself. This may help Celehar’s long-term survival prospects. Then again, it may not, as even the emperor’s respect for Celehar will not cause him to dismantle the Clenverada Mining Company on his word alone, when doing so may threaten the empire’s stability. But the emperor is a man of ethics and deep conviction, and he, too, finds atrocity displeasing.

This is a measured, meditative novel, as much concerned with introspection as with action. It reminds me – more strongly than any of its predecessors – of The Goblin Emperor, intimately focused on questions of integrity and responsibility, on duty and self-knowledge and the difficulty and reward of human connection. It is, too, concerned with religious relationships: the nature of a calling, the difficulties of religious bureaucracy, the difference between a gift and a burden. The prose, as ever with Addison, is beautifully composed, while the characters are painfully, compellingly human. It is a novel where the world is not always kind, nor always just, but where the characters strive for better. It is a piece of art that fed something in me that I had not known was hungry. I adore it. I can only hope that the openness of this ending means Addison will one day write more stories featuring Celehar.

Interested in this title? Your purchase through the links below brings us a small amount of affiliate income and helps us keep doing all the reviews you love to read!

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, is out now from Aqueduct Press. Find her at her blog, her Patreon, or Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.

This review and more like it in the January 2025 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.