Gliff by Ali Smith: Review by Niall Harrison

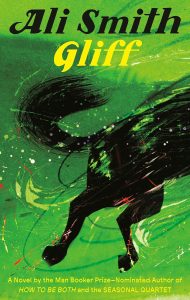

Gliff, Ali Smith (Hamish Hamilton 978-0-24166-557-2, £18.99, 288pp, hc) October 2024. (Pantheon 978-0-59370-156-0, $28.00, 288pp, hc) February 2025.

Gliff, Ali Smith (Hamish Hamilton 978-0-24166-557-2, £18.99, 288pp, hc) October 2024. (Pantheon 978-0-59370-156-0, $28.00, 288pp, hc) February 2025.

If one definition of literary voice is that it is the combination of what a writer’s sentences pay attention to and how they pay attention to it, then Ali Smith’s voice is one of the most distinctive of the twenty-first century. What her sentences pay attention to are the political and linguistic structures that make up the contemporary world, and how they do it is by being playful, clever, engaged, and careful, such that on any given page you are liable to encounter piercing similes, intellectual riffs, shameless puns, and steely moral clarity, in snappy prose typically heavy with dialogue but stripped of any of the common markers of such. I find it an intoxicating and utterly distinctive mix. One of the epigraphs to her 2002 novel The Accidental is taken from John Berger, speaking of the gap between “the experience of living a normal life at this moment and the public narratives being offered to give a sense to that life,” and not just that novel, but much of Smith’s career, across twelve other novels and five short story collections since 1995, can be taken as an attempt to close that gap. And as her subject matter has become more deliberately present-tense – the Seasonal Quartet (2016-2020) was described by Smith as “a sort of time-sensitive experiment,” because the novels were deliberately written and published as close to current events as possible, and they became an indelible running commentary on the state of the UK from Brexit to COVID – it has been more tempting to speculate about what would happen if she went that little bit further.

Put another way, if one definition of genre is that it is a set of expectations about what a story pays attention to, I’ve been unable to stop myself wondering how science fiction might modulate Smith’s voice. With Gliff, we have the answer: It’s the other way around. This is not a criticism. What it means is that Gliff is an excitingly unusual science fiction novel. There are many strongly voiced authors working within different genres, and there are many authors who can switch and do interesting things across multiple genres, but I can’t think of many other authors with a voice strong enough to simply render pre-existing reader expectations of a genre moot. One of the few prior examples that comes to mind is Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006) – a very different novel to Gliff in many ways, but what the two novels share is that both feel dominatingly voice-driven. This is true even as the underlying narratives in both cases are straightforward, even familiar.

Gliff is a near-future dystopia. Its themes have clear roots in current British politics, in particular the treatment of those from Roma and Traveller backgrounds, whose situation has featured in some of Smith’s other novels, and who (when analysed as a group in government statistics) have shorter life expectancy, worse educational outcomes, and worse access to services than other UK demographics. Stylistically, Gliff aligns itself with the early twentieth-century modernist tradition, and textual playfulness, of Zamyatin and Huxley. Several chapters begin with declensions of the phrase “brave new world,” with different letters dropped out or interpolated each time: “brave new word,” “brave new o ld,” “brave you world,” and so on. The narrator throughout is Briar, or possibly Brice, a teenager who at the start of the novel is left with their younger sister, Rose, to squat in an abandoned house, while the man who leaves them, Leif, attempts to extract their mother from the situation she is in. We hear no more about the adults. It is possible we will re-encounter them in a promised companion novel, Glyph, which will apparently tell a story “hidden within” Gliff, but we might not; part of Smith’s conception of dystopia is that it is a state of being in which people’s stories are disjointed and disrupted, where beginnings are not always salved by endings. At any rate, Bri and Rose are on their own for this novel, and outside the system of the dystopia, “unverified” in the terms of that system. They encounter other unverified and Bri, who like many young Smith protagonists before them is fascinated by language and polysemicity, understands them as “unverifiable because of words,” which is to say people who have accurately called out war as war, or genocide as genocide, or stated facts such as the fact that oil companies bear direct responsibility for climate crisis. They encounter, ultimately, the operatives of the state.

But to describe the narrative like this is to construct the dystopia in a more direct way than Smith ever does in the novel, which is part of what makes it feel so fresh. The word “gliff” is Scots, with enough meanings that it takes Smith, when Bri finds a dictionary, two pages to run through them all. You could use every definition as a filter to highlight different aspects of how the novel works, but the two most relevant for me are “a transient glance” and “an unexpected view of something that startles you.” Gliff is dystopia seen in fits and starts, as a set of conditions that shapes and limits Bri and Rose’s existence, and periodically impinges on them directly, but is nevertheless only part of their lives, not the whole of them. A substantial chunk of the novel, for instance, is spent on their relationship with the horses they find in a field at the back of the house that Leif leaves them in, a relationship which is by turns tender and funny and sad. Bri talks about how the horses smell (“deep and hearty and unlike anything I knew”), about how they move, about how beautiful they are, about how they make her feel “equanimity” (the pun is definitely intentional); then they gradually realise the horses are destined for the abattoir, a scenario that neither sibling is fully equipped to deal with, but they try to save one by bringing it into their accommodation, with surprising success (“a horse is half a ton of panic on a rope,” one character warns; “So don’t put a horse on a rope,” Rose states firmly, and gets away with it).

Nothing in an Ali Smith novel is only there for one reason, however, so the horse also becomes a marker in an ongoing debate about the power of names. It’s not an accident that Briar and Rose are folktale-derived names, but the novel suggests that the siblings have to learn to resist the connotations that come with them – to give them, in effect, more meanings. (One character also pointedly critiques the story they are taken from in ecocritical terms, wishing for a writer with “talent enough to write a song solely about two beautiful plants… with no human inference at all to be taken from it,” suggesting the kinds of action and meaning that are important.) Late in the novel, a key act of resistance is signalled by shouting a word whose meaning will be incomprehensible to anyone who hears it, because its meaning comes from a private and personal context; and the name that Rose gives to the horse is, of course, Gliff, a new meaning not dreamt of in Bri’s dictionary. In all these cases, it’s the possibility of multiple meanings that is freeing; more than that, the impossibility of a single meaning in any sufficiently free society. I think that, above all, is what Ali Smith wants us to pay attention to here, and it’s a very Ali Smith way of reaching a very science-fictional conclusion.

Interested in this title? Your purchase through the links below brings us a small amount of affiliate income and helps us keep doing all the reviews you love to read!

In Niall Harrison‘s spare time, he writes reviews and essays about sf. He is a former editor of Vector (2006-2010) and Strange Horizons (2010-2017), as well as a former Arthur C. Clarke Award judge and various other things.

This review and more like it in the January 2025 issue of Locus.

This review and more like it in the January 2025 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.