Spells to Forget Us by Aislinn Brophy: Review by Alex Brown

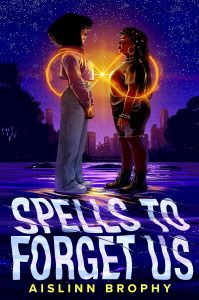

Spells to Forget Us, Aislinn Brophy (Putnam 978-15586-1331-7, $20.99, 432pp, hc) September 2024.

Spells to Forget Us, Aislinn Brophy (Putnam 978-15586-1331-7, $20.99, 432pp, hc) September 2024.

In Aislinn Brophy’s new young adult romantic fantasy Spells to Forget Us, two Black teen girls have to balance falling in love with neglectful parents and harsh community expectations. Luna Gold and Aoife Walsh meet-cute at a high school football game. They flirt, they go out, they get together, they break up. Turns out, this isn’t the first time they’ve had their romantic meet-cute and it won’t be the last. Luna is the youngest heir to a powerful magical family in Boston. She’s expected to marry another witch and have lots of witch babies and continue consolidating the Gold family position. What she absolutely is not allowed to do is date a mundane. Which is a problem when she falls for Aoife, a nonmagical girl. Magic is everywhere, but mundanes are blocked from seeing it by an ancient spell. Luna has also inherited the unfortunate family trait of having to pay a cost for casting a spell. So when Luna breaks the spell that prevents Aoife from seeing magic, the price is that if they ever split up, both of them will forget the other ever existed. This goes about as well as you’d expect.

Aoife and Luna keep finding their way back to each other, and each time their relationship gets harder to maintain and even harder to end. The longer this goes on, the more their families start to suspect something is up. The pressure is on to find a way out of these magical consequences while also freeing themselves from their parents’ impossible expectations and demands. They just want to be two girls in love, but life, magic, and parents keep getting in the way.

Parenting is a major theme in Spells to Forget Us. Luna and Aoife both have parents who aren’t necessarily bad or abusive, but also aren’t thoughtful or observant. Their parents (and in Luna’s case, grandmother) have forgotten that their children are people with thoughts, feelings, wants, and needs. For Aoife, she’s literally her parents’ moneymaker. They mine her personal life for their parenting content mill so much that she’s petrified of telling them anything. She can’t go to them as parents; she can only interact with them as employers. No matter how much she hints at wanting out of the influencer life, they cannot or will not hear her. Likewise with Luna’s grandmother, Grandma Gold, the family matriarch. Her parents despise each other (they married only because Grandma Gold decided it would be politically expedient) and so spend as little time participating in familial activities as possible. Grandma Gold sees Luna as a pawn to move around a chess board or a soldier on the field to command. She fully intends to use Luna to further ensure her legacy and security just like she did with Luna’s parents, and it doesn’t matter how miserable it makes any of them.

The latter is a situation that many Millennial and younger Black folks are intimately familiar with. As Brophy explains, this isn’t just an elder being tough on a younger child or having ludicrously high expectations. There’s a specific dynamic happening between Luna and Grandma Gold. Older generation Black folks – we’re talking those who grew up in Jim Crow and/or knew elders who were either freed from or one generation removed from slavery – can sometimes end up smothering their children unintentionally because of generational trauma. Grandma Gold had to fight for everything she has now. She went up against a centuries-old system of racial oppression and misogynoir. Everything she does is to leave a better world behind for her descendants. She wants Luna to have what she deserves without having to claw it out of the hands of racist white people. She wants this so desperately she can’t even acknowledge that Luna might not want the same things she fought to gain. She’s also forgotten that freedom isn’t just about getting access to the same things white people have but getting to choose what you do with your life. She feels that Luna is disrespecting and disregarding all the pain she went through, while Luna just wants her grandmother to relax her definition of success a little.

Two other conversations I don’t often see in young adult fantasy that Brophy digs into here are colorism and the fetishization of biracial people. Aoife is light-skinned and biracial Black and white, just like I am. Like Aoife, I’m very aware of the privileges I’m afforded over my kin with darker skin, and how tempting it is to tap into that proximity to whiteness to insulate myself against the worst racism. Yet we also know that even though it might take a little longer to get to us, we’re still subject to anti-Blackness and tokenization. Then there’s the added layers of white people treating you like you’re the ‘‘solution’’ to racial strife – I can’t tell you how many times growing up I heard that my existence proved that racism was over – and the fetishization of your skin tone and hair texture as some sort of exotic treat.

Black folks always treated me like a Black person, but white folks often treat me like I’m not really Black and definitely not white but some sort of special third thing that they can use as a model minority. You’re ‘‘the good one’’ or ‘‘not like those other ones.’’ Add to that growing up in a predominately white space, it feels impossible to be truly seen as a biracial Black teen. Brophy thoughtfully explores that tension between using your privilege to make space for those without, pushing back against colorism (both within the Black community and without), and acknowledging the specific challenges that come with being a lighter biracial Black person in a white supremacist society.

Given the ending, I wouldn’t call this a romance novel, but I loved the ending anyway. Brophy gave them an ending that felt realistic and honest. Luna and Aoife end up in a situation that is both bittersweet and hopeful. They make the responsible choice even though it’s the one that hurts the most. Showing teens that romantic relationships can be complex, that there is a gray area between ‘‘together’’ and ‘‘broken up,’’ is so important. A lot of teens are navigating their first real relationships and only have what they see in media or in their friend groups as examples. This offers a nice counternarrative.

Even after all this, there is so much more to talk about! Aislinn Brophy explores the patriarchy and toxic masculinity, the way communities of color are set up by white supremacy to compete with each other, the dangerous sides of social media, parasocial relationships, queerness, neurodiversity, and on and on. I picked up Spells to Forget Us expecting a light, frothy fantasy romance but instead got heartfelt conversations about big topics that aren’t discussed nearly enough. This was an excellent sophomore novel.

Interested in this title? Your purchase through the links below brings us a small amount of affiliate income and helps us keep doing all the reviews you love to read!

Alex Brown is a librarian, author, historian, and Hugo-nominated and Ignyte award-winning critic who writes about speculative fiction, young adult fiction, librarianship, and Black history.

This review and more like it in the December 2024 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.