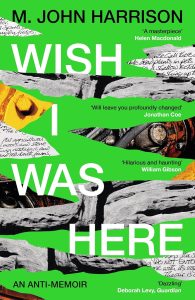

Wish I Was Here by M. John Harrison: Review by Niall Harrison

Wish I Was Here, M. John Harrison (Serpent’s Tail 978-1-80081-297-0, £16.99, 224pp, hc) May 2023. (Saga Press 978-1-66806-304-0, 224pp, $26.99, hc). September 2024.

Wish I Was Here, M. John Harrison (Serpent’s Tail 978-1-80081-297-0, £16.99, 224pp, hc) May 2023. (Saga Press 978-1-66806-304-0, 224pp, $26.99, hc). September 2024.

It’s hard to know where to start writing about a book that knows exactly what it is and knows that knowledge doesn’t help much. “When [a piece of writing] has been assembled like this one,” writes M. John Harrison, “from so many layers of your life… reading it is like trying to interpret your own geological nonconformities and discontinuities.” Wish I Was Here is subtitled “an anti-memoir,” which I think served as a reminder to its author as much as it does a guide for its readers. You will not find, within these pages, very much clear biographical information, and what there is, is not in a strict chronological order. There is a reference to growing up “entry-level middle class,” “somewhere in the Midlands”; passing mentions of moves to London, and the Peak District, and London again, and then out West to Shropshire; little discussion of family, friends or colleagues, and those who are mentioned tend to be obscured by aliases and may be composites or entirely fictional. And there is very little discussion, also, of specific published works. There is a mention that Harrison’s first short story was published in 1966, and the novel that he clearly sees as a linchpin not only of his career but of his writing life, Climbers (1989), merits some discussion (although not as much as climbing itself, which is clearly a linchpin of his actual life), but if you don’t already know about the entropic fantasies of Viriconium (1971-1991), or the startling unstable science fiction of the Kefahuchi Tract trilogy (2002-2012), or the eerie refracted UK of The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again (2020), which netted him the Goldsmith’s Prize in the UK and at last a measure of mainstream recognition – well, if you don’t already know about those works, you won’t learn about them here. The best place to start for that sort of thing might be Parietal Games (2005), which does us the great service of collecting Harrison’s own critical writing alongside a variety of perceptive essays about his life and work.

But what we have here is something else, a series of jumbled cross sections through the sedimentary layers of Harrison’s life. It is divided into four sections, and within that into chapters, and within that into paragraphs separated by blank lines, each paragraph capturing an idea or image. Many paragraphs are drawn with a greater or lesser amount of revision from notebooks that he has kept throughout his life, or from other already-published sources, including his blog and, in at least one case, New Scientist. It is, I think, an attempt to represent his thinking as it was at the time, not just how he recalls it now. More than once he expresses wariness of memory, sometimes fearing the loss of relevant detail, but at other times fearing the gain of certainty, mistrusting any sense of meaning. “Much of life,” he insists, “you will never know what happened to you at all…. the search for causality is to welter around looking for explanations you can’t have.” As with many of the you-statements in the book, you sense that Harrison is insisting to himself as much as to us. The gap between experience and the communication of that experience is unbridgeable, and to be a writer is not to attempt to bridge that gap, but to acknowledge and attempt to process the fact that the gap exists. This mindset is surely the thing that makes his writing so distinctive.

I almost wrote, “his speculative writing,” because that more qualified statement is just as true, but he would surely bristle at the notion of such a division. Because within the bricolage of Wish I Was Here, alongside semistraightforward memoiristic material, there is fictional material, semifictional material, speculative material, and critical material, and a lot of material that falls into more than one of those categories at once. It is best approached simply as a piece of writing, with as few expectations as possible. From the point of view of someone reading from within the SF community, it is certainly interesting to know that the book contains a synopsis for a five-volume epic fantasy series, or that it includes Harrison’s thoughts on topics such as ghosts, the weird, and disaster novels, and such discussions are typically stringent. His critical perspective focuses on the moment that language is activated, immediately obscuring the underlying experience, and – crucially – upstream of any patterns or categories. Naming has a purpose – I was struck by his suggestion that the UK’s “post-industrial, post-Imperial melancholy, which was an anxiety of the modern” is “giving way to something different, something which needs to be voiced before we can perceive it” – but is immediately insufficient. Reflecting on the concept of liminality, he observes with weariness, that “a kitsch of liminal zones is now inevitable.” Categories feel to Harrison like “gentrifying labels” as soon as they are identified, because they defuse the distinctiveness of an individual text.

He is not the only writer to feel this way, but he is more successful in his resistance than almost any other writer I can think of. To read M. John Harrison, in this book or any other, is for me an experience studded with salience shocks: His sentences turn your attention in a manner that you don’t anticipate, to look at things you hadn’t considered. He is relentlessly attentive to how language is being used and is evolving. In an interview given to The Guardian at the time of Wish I Was Here’s UK publication, he suggested that he wanted to learn how to imitate ChatGPT’s prose – by definition, purely pattern-driven text – I think because inhabiting a style is the first step to resisting it. That is his approach throughout this book. Wish I Was Here, as it segues between its fictional and non-fictional material, attempts both to articulate a theory of practice and to embody that theory in practice. Perhaps one scene from late in the book can exemplify the effect. It relates what appears to be an utterly mundane exchange with one of the composite/alias characters, Bea, about a trip to buy paint for decorating. Yet it is so laced with uncanny potential energy that for a moment I thought I was reading a deleted scene from Sunken Land (maybe I was); and at the same time, it made me feel the way that Harrison describes himself feeling after a viewing of Antony Gormley’s artwork Blind Light: “totally elated, as if I’d remembered something real.”

Interested in this title? Your purchase through the links below brings us a small amount of affiliate income and helps us keep doing all the reviews you love to read!

In Niall Harrison‘s spare time, he writes reviews and essays about sf. He is a former editor of Vector (2006-2010) and Strange Horizons (2010-2017), as well as a former Arthur C. Clarke Award judge and various other things.

This review and more like it in the October 2024 issue of Locus.

This review and more like it in the October 2024 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.