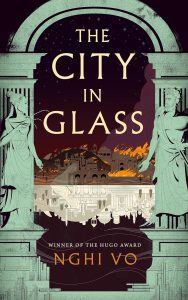

The City in Glass by Nghi Vo: Review by Jake Casella Brookins

The City in Glass, Nghi Vo (Tordotcom 978-1250348272, $24.99, 224pp), October 2024.

The City in Glass, Nghi Vo (Tordotcom 978-1250348272, $24.99, 224pp), October 2024.

If you’ve read any of Nghi Vo’s earlier work, you already know that she’s a writer to watch – a masterful stylist with a flair for bringing together magical premises, subtle anthropological worldbuilding, and deep wells of mythic imagery and themes. If you haven’t, Vo’s newest, The City in Glass, is not at all a bad place to start. Eschewing quest narratives and traditional plots, it’s a wholly place- and character-based story, layering a rich love for fantasy settings with an intimate and somewhat ambiguous arc of grief, vengeance, and forgiveness.

The novel centers on Vitrine, a demon. What that means in the cosmology or theology of this world is never entirely clear – Vitrine and her kin don’t seem to fall on or fight for any simplistic moral axis – but it does mean that she’s immortal, full of strange though not unlimited powers. Where other demons pursue their own passions and interests, some sleeping deep underground, some roaming the earth, Vitrine has fallen in love with a port city, Azril. Over the centuries, she’s shaped its culture and its inhabitants, tweaking it like a perpetual art project – until, for reasons unknown, angels appear and level the city. Cursing one of the destroyers with all of her rage and grief, such that his brethren cast him out, Vitrine spends long decades grieving, rebuilding, shaping something new over the old foundations, dogged by the exiled angel.

Vo handles time extremely well in The City in Glass. Chapters move organically back and forth between Azril-before, its long centuries of development and intrigue, and Azril-after, the new thing that grows after the apocalypse. Vitrine’s long period of mourning and manual labor stand sharply between them, and her sense of Azril-after is colored by loss and, perhaps more devastating, her new awareness of fragility. Long used to humans’ short lives, she’s deeply traumatized by cultural mortality, and the alternating time frames add a layer of emotional richness to both the past and the present scenes: the past with its promise of what could be again, the present with the foreknowledge of its own ephemerality. Although Vitrine is very much about life, about the actual food, art, and music of the city, its actual people, she – and the novel as whole – is also very much about memory. Libraries figure centrally, and Vitrine herself, in a bit of magical realism that works all the better for never being fully explained, contains a glass cabinet, that contains a book, that contains the records and the names of all her time in Azril.

And really, as much as Vitrine and her tempestuous relationship with her eventually grounded angel provide the emotional backbone to the novel, they feel almost secondary – in a good way – to the novel’s core project, which is just to give us many windows and views on a fantastic city. Vitrine thinks of Azril as a garden, as a party, as a lover, as an extended family quarrel that she intends, eventually, to win. Vignettes throughout the novel introduce us to Azril’s painters, its plagues, its politicians and cliff-dwelling penitents; the novel is no futile attempt to totally contain a city, but a lovely and riotous selection of the kinds of lives and loves within it. “No one loves a city like one born to it, and no one loves a city like an immigrant.” Although there are plenty of magical elements scattered throughout – an allusion to a dangerous unicorn, a bottle filled with singing dust that was once an angel, a demonic sigil that prompts riots and raves – the city itself feels intensely real, intensely and lovingly urban, brimming over with the kind of cultural detail that Vo excels at working into the text. It’s a rare quality in a fantasy city, and had me thinking of Samatar’s Bain and Chandrasekera’s Luriat.

That vividness makes the novel’s instigating disaster all the more affecting, and all the more disturbing. Is it still a disaster if someone chose to make it happen? Perhaps atrocity is a better word. We don’t know why the angels come for Azril, but they come like an atom bomb, destroying everything for miles around; Vitrine wonders “with brief bitterness what share the frogs and snakes and turtles lived among the wild cane had had in the angels’ punishment.” She spends years clearing the city of human remains, remembering each by name. This atrocity sits, unforgiven, in Vitrine and in the novel. For me, at least, “fantasy novel” is no emotional insulation against “bombing the innocent,” and one of the sickening tensions while reading this was the constant worry: is Vitrine going to forgive the angel? Is this going to be some pat story of healing and moving on?

It is not, thank goodness, anything so simplistic, though Vitrine and the angel are one of the trellises the story grows over, with a compelling bitter chemistry. Vo’s displayed great range and depth in character in her other work, but Vitrine is the deepest study in anger I’ve seen in a long time. How that plays out in her relationship with the angel, over decades and centuries, is really satisfying. There are points here, I think, about how weapons and cities are fundamentally opposed, and about how – as some of her favorite humans gently remind Vitrine at points – cities, magical as they can be, are just places, and sometimes it’s time to leave. As readers, we can only visit Azril for a little while, and The City In Glass is as fine a guide, a historian, and a host as one could ask.

Interested in this title? Your purchase through the links below brings us a small amount of affiliate income and helps us keep doing all the reviews you love to read!

Jake Casella Brookins is from the Pennsylvania Appalachians, and spent a fantastic amount of time in the woods. He studied biology, before switching over to philosophy & literature, at Mansfield University. He’s been a specialty coffee professional since 2006. He’s worn a lot of coffee hats. He worked in Upstate New York and Ontario for about 8 years. He’s been in Chicago since 2013; prior to the pandemic, he worked for Intelligentsia Coffee in the Loop. Starting in 2021, he’s been selling books at a local indie bookstore. He lives with his wife, Alison, and their dogs Tiptree & Jo, in Logan Square.

This review and more like it in the September 2024 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.