Wole Talabi Reviews In the Shadow of the Fall by Tobi Ogundiran

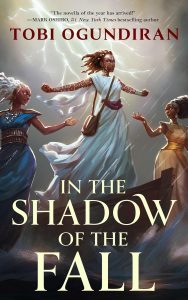

In the Shadow of the Fall, Tobi Ogundiran (Tordotcom 978-1-25090-796-7, $20.99, 160pp, hc). July 2024.

In the Shadow of the Fall, Tobi Ogundiran (Tordotcom 978-1-25090-796-7, $20.99, 160pp, hc). July 2024.

Less than a year ago, Tobi Ogundiran presented us with Jackal, Jackal, a delightful selection of dark tales accessibly infused with legends and folklore. One of those stories was ‘‘Guardian of the Gods’’ (first published in FIYAH), which tells the story of Ashâke, an acolyte who can’t hear the gods speak. I reviewed it for Locus then, and in a part of the review that was eventually cut for brevity, I described it as ‘‘an exceedingly well framed tale… which could be the first act of a larger story.’’

In the Shadow of the Fall is the first part of that larger story. Telling this story in novella form gives Ogundiran the room to make it about more than the mystery of why Ashâke cannot hear the gods. It’s a true expansion with new scenes and story elements that reinforce themes, flesh out the world, fill in details of events that were only hinted at, and introduces a cast of new characters, including a terrifying new villain. It all works well, making this novella well worth the read.

The story takes place in what appears to be a secondary world inspired by West Africa. There, in a brilliant new opening scene, we meet Ashâke, an acolyte in the Ifa temple, as she is desperately trying to summon and trap one of the Orisha (gods from Yoruba mythology who seem to be having a moment in contemporary SFF) in a vessel called an idan. She has resorted to this forbidden act because of all the acolytes, she is the only one who cannot hear the Orisha, which is why she is yet to accede to the priesthood five years after she should have. But the summoning goes wrong; she sets a sacred grove aflame, is struck with visions and injured. Imprisoned by the high priests while being treated by the witch doctor Ba Fatai, she comes to learn that perhaps her place is not at the temple and escapes. She runs into a group of kindly griots, including the memorable Mama Agba and her nephew Djola, who take her in and treat her like the family she has never known. But the vision triggered by her summoning has drawn the attention of a powerful sect that follow one called Bahl’ul, The Teacher. Yarrudin, a ruthless member of this sect, is sent to seek her out even as the temple tries to find her and bring her back. In a series of rapid revelations, Ashâke learns why the gods have been silent, about a cosmic war ignited hundreds of seasons ago, and that she herself is a vessel (an idan of sorts) for the Orisha with a greater purpose. All this as she tries to escape Yarrudin and the followers of The Teacher.

It’s an engrossing and fast-paced story, one that I suspect most readers will consume in a single reading or two. The characters feel real enough for us to form emotional connections to them, and the ending resolves itself satisfactorily while clearly leaving scope for the necessary sequel (this is the first half of a duology). The theme of belief and its interaction with godhood is always an interesting one and is explored here, highlighting how the griots, the followers of The Teacher and the temple all use the power of narrative as a tool in the cosmic war gone cold.

The prose is clear and vivid, and while I found myself yearning for more Yoruba-inspired linguistic creativity, or some other stylistic marker to establish this as the African story it is, the prose is effective for telling a story of this scope at this length. That isn’t to say there are no clever stylistic flourishes. The scenes where the griots literally sing events with such power that all who hear them are immediately transported, as though they were really there, were a highlight. Something that harkens to the power of the spoken word in many African cultures, and I think, a brilliant a literary device for ‘‘showing’’ events and ‘‘telling’’ them at the same time.

They Sang without koras or flutes or drums. They Sang without embellishment or ceremony. There was only their voices, blended as one in grief, in pain, in defiance.

The world dissolved. Away fell the riverbank littered with bodies, away fell the boiling river and the burning boats. Ashâke felt the magic of their Singing as she was sucked into the depths of a Memory.

Immersive, entertaining, and well-crafted, with an atmospheric tone and an intriguing cast of characters, In the Shadow of the Fall is a small African epic fantasy with big scope and big stakes, and I look forward to its conclusion.

Wole Talabi is an engineer, writer, and editor from Nigeria. He’s hopped around the planet quite a bit but right now, he lives in Malaysia. His stories have appeared in Asimov’s, Lightspeed, F&SF, Clarkesworld and several other places. He has edited three anthologies and been a finalist for several awards including the Caine Prize, the Locus Award, and the Nommo Award. His work has also been translated into Spanish, Norwegian, Chinese, Italian, Bengali, and French. His collection Incomplete Solutions (2019), is published by Luna Press and his debut Novel Shigidi, will be published by DAW books in fall, 2023.

This review and more like it in the May 2024 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.