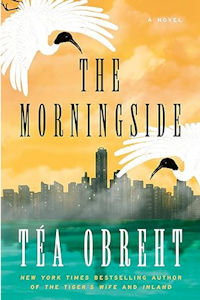

Paul Di Filippo Reviews The Morningside by Téa Obreht

The Morningside, Téa Obreht (Random House 978-1984855503, hardcover, 304pp, $20.00) March 2024

The Morningside, Téa Obreht (Random House 978-1984855503, hardcover, 304pp, $20.00) March 2024

Is the New Weird still a going concern? Dating roughly from the turn of the century (China Miéville’s Perdido Street Station is the Monolith that enlightened the hominid readers), with the term itself harking to the year 2002 (courtesy of M. John Harrison), the subgenre with famously leaky borders and hazy definitions is approaching its 25th birthday. That seems young in human terms, but somewhat more creaky for a once-trendy mode of fiction. And yet cyberpunk and steampunk, older both, are still extant story-telling approaches, so there’s no ruling out New Weird just by its age. And in fact, a cursory, time-delimited Google search of the term reveals some 40,000 hits for the past year, including a nice little introductory piece from early in 2024 in The Sydney Morning Herald.

With the arrival of Téa Obreht’s well-wrought, charming, and quietly bent third novel, the tale of an oddball city (and world) lateral to our universe, I think we can confidently say that New Weird has the capacity still to astound us, while piercing fresh new territories. Obreht cites Gabriel García Márquez as an influence on all her writing, and so, I suppose, mainstream literary critics might be tempted just to call this book “magical realism.” But to the eyes of a genre reader, Obreht deploys her tropes and plot and characters in a manner utterly consistent with the New Weird template, such as it is, and thus, I believe, claims a place in the New Weird canon.

Ninety percent of our book takes place in one marvelous venue: Island City, and specifically one residential building there, the Morningside. Now, the first thing we perceive is that Island City is basically a semi-drowned Manhattan. Its landmarks (under alternate names), its social structure, its remaining subways and streets, correspond to our New York City. But they have all been imbued or lacquered over with a magical aura that does not obscure or invalidate the very quotidian pursuits and lives being lived therein. As with those two bards of such a metropolitan fantasy—John Crowley and Mark Helprin—Obreht achieves a perfect blend of the mystical and the domestic.

A first chapter gives us our narrator—somewhat mysteriously, without context—as a knowing adult. Several denouement chapters will feature her again as an adult, many years after the main action has ended. (These tie in beautifully, in retrospect, with the opener.) But for most of the book, she is eleven-year-old Silvia, in mind and voice, telling us in first-person the astonishing tale of a year or two from her adolescence.

Silvia and her indomitable mother are immigrants to the country (this quasi-USA) that features Island City. They are fleeing war and turbulence “Back Home,” and have been resettled by the Repopulation Program. (This departmental moniker slyly conjures up an apocalyptic backstory of population loss which Obreht calmly never explains.). This immigrant/émigré/refugee aspect of the book is a vital, important thread, and surely reflects Obreht’s own intimate background as a Yugoslavian transplant to America.

The relationship between Sil and her over-protective, feisty mother contours the whole book, and gives us a domesticity angle to the New Weird trappings which I think has been lacking in previous examples of the genre.

Sil and Mom go to live with Aunt Ena in the fabled Morningside building, a shadow of its old (Upper West Side?) elegance. Ena is the building’s super, a job and title which eventually passes to Mom. Sil cannot be enrolled in school, and so has to spend her time exploring the building and, eventually, the city. But two important personages soon intrude into her life.

One is Bezi Duras, an elderly famous woman painter who resides in the penthouse of the Morningside. Aloof and eerie, she is always followed by a pack of large dogs. Her spooky aura would allure any imaginative inquisitive child, but Sil soon realizes that there is even more to Duras than is obvious.

Duras must be a “Vila,” a powerful demigod represented in the myths of Back Home. There’s no other explanation for her doings. And so Sil makes it her mission to expose and/or befriend Duras. This mission informs much of the plot.

But there’s another strange figure hanging around the Morningside: Lewis May, a Black man who is a disgraced writer, forced to retire and to do—do what exactly? He seems harmless and friendly, but there is plainly more to him than meets the eye. The big reveal about him is a shock.

So Sil’s life oscillates between the three strange attractors of mother, Duras, and May, until a fatal fourth element is introduced into the equation. A girl the same age as Sil, Mila, moves into the building with her family. Mila is bolder and brassier than Sil—“Hard as stone, all the way down.”—and soon the pair are breaking into Duras’s penthouse and following the woman across the city on her enigmatic errands. All good fun, until the Vila manifests….

Obreht’s portrait of the city and its inhabitants is rich and granular. One might at times recall Delany’s Bellona, or Richard Kadrey’s European burg from The Grand Dark; Ballard’s Drowned London or the fabulous metropolis found in Chandler Klang Smith’s The Sky is Yours. It also shows some of that old-school New York magic that entranced Thomas Wolfe.

All around me lay the city, with its steeples and junkyards, its beaches of waterlogged debris, its water towers and mussel-laden piers, and the roaming tide. And everyone in it—the neighbors; sneering Mrs. Gaspard; Mrs. Sayez, with her sweet, dull kindness; the entirety of the Dispatch, that faceless murmuration outspread among the different neighborhoods; the Dancing Girls on their billboards; and May; and even and especially my mother—they all inhabited the same world, in which Bezi Duras was just a painter.

As in that famous time disjunction in Little, Big, Obreht, for her closure, catapults Sil and her mother and Lewis May years beyond the critical events (and across the country), and the cascading revelations of what the whole affair really meant are not without their own drama and even suspense.

This book is pure unpredictable but organically and esthetically coherent pleasure from start to finish. If Kim Stanley Robinson and Lisa Goldstein had conspired to rewrite Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy, the result might resemble Obreht’s luminous creation.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.