Niall Harrison Reviews Mad Sisters of Esi by Tashan Mehta

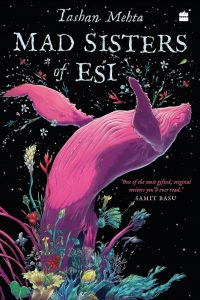

Mad Sisters of Esi, Tashan Mehta (HarperCollins India 978-93569-94188, 412pp, INR599.00, tp). September 2023. Cover by Upamanyu Bhattacharyya.

Mad Sisters of Esi, Tashan Mehta (HarperCollins India 978-93569-94188, 412pp, INR599.00, tp). September 2023. Cover by Upamanyu Bhattacharyya.

Towards the end of Tashan Mehta’s scintillating second novel, Mad Sisters of Esi, there is a single-page chapter titled “Breathe”. “We pause here,” the narrator tells us. “We sit down. We rest…. There is no rush.” It comes at exactly the right time. The “we” speaking at this point (this is a multivoiced book) is a chorus of ghosts who have been listening to one of the titular sisters, Magali, recount her life story, and it has shaken the collective’s understanding of their history, so it makes sense for them in character; but it’s a good reminder to the reader as well, who might be tempted to rush on to the end, to reflect on the novel’s revelations and accomplishments. I closed the book and went for a walk.

It’s not that Mehta has written a breathless thriller: The intensity of the novel is imaginative and emotional. To take the imaginative first: at over 400 pages, it sustains and elaborates an invented cosmology that, if someone were summarising it to me, I might think bizarre enough to only work at short story length. There is, to begin with, a whale that is also a growing universe; it contains 780 recorded world-chambers, with more constantly appearing. Within the whale live its keepers, Myung and Laleh, sisters who understand that they were created by Wisa, who also created the whale itself, but has now vanished. The whale swims through space, which everyone in the novel calls “the black sea,” a reframing that an academic explains is about learning to see “what we considered empty as full and unfathomable,” and that “what appeared storyless was only unknown”; as part of the same reframing, planets, such as Esi, are now referred to as islands. Sideways to all of that is the Museum of Collective Memory, which can be accessed from wherever you are by tapping your ear and saying the correct word, and at the centre of the Museum is a living island called Ojda, where the chorus of ghosts can be found.

There is joy in simply following Mehta’s imagination. Some of the best details are to be found in the occasional excerpts from Myung’s diaries, after she has left the whale to explore the black sea – she has an “eagerness for novelty” that Laleh does not. She might casually describe a game that can only be played using moon-white fish bones that are over a century old; or she might explain the nature of “craft,” which seems to be an integration of different ways of understanding the universe and which allows extraordinary manipulations of reality. Comparisons with other writers are not impossible, but risk being more than usually misleading. The use of chorus, and the nested architecture of the story, are in some ways similar to what Simon Jimenez gets up to in The Spear Cuts Through Water, but conceptually it’s more as though one of Karin Tidbeck’s wilder stories, or one of Italo Calvino’s cosmicomics, had somehow seamlessly been expanded into a novel. There is a constant sense of experimentation and exploration.

The heart of the book, however, is the two sisterly relationships and the family history that connects them. We begin with Myung and Laleh, who meet early in the novel, inside the whale, and decide to be sisters. Via different routes, they seek answers about their origins and the origins of the whale, which leads them to the titular sisters, Magali and Wisa. They lived generations earlier on the living, shapeshifting island of Esi, “a place not quite docile and with more history than your mind can comprehend.” Perhaps the best part of the novel is the long section given over to Magali and Wisa’s story, a beautifully observed portrait of childhood and adolescence in the years leading up to Esi’s “festival of madness,” defined as a time “outside of understanding,” when everything is fluid and subject to change: a strange time, in other words, that is fraught with both possibility and peril. Mehta builds a rich vision of humans as part of a world in which “there are as many forms of consciousness as there are hearts,” within which Magali and Wisa live with “reverential awe… as part of a network of seeing and doing.” It is also a vision of human relationships as entanglements across time, and it fully captures both the beauty of travelling alongside a soul for a time, and the pain of not always being together in the same time: of what happens when someone is “the right person, just not the same person” as when you last saw them.

So all in all, the end of Magali’s story really is a good time to take a breath. Mad Sisters of Esi is a rich novel, and the stories it tells should be savoured while you’re reading them, not least because Mehta reminds us that stories always change over time, as they are retold or re-encountered. I can only hope my brief exposition here has done her novel some sort of justice and look forward to my own certain future of re-encountering the four sisters. (To say nothing of the whale.)

In Niall Harrison’s spare time, he writes reviews and essays about sf. He is a former editor of Vector (2006-2010) and Strange Horizons (2010-2017), as well as a former Arthur C. Clarke Award judge and various other things.

This review and more like it in the December and January 2023 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.