Ness Brown Guest Post

For most of human history, on clear nights our species could marvel at an untarnished view of nearly 3,000 stars. This view, shared by civilizations around the globe, was a wellspring of awe and speculation out of which flowed diverse myths and philosophies. Countless cultures have long traditions that connect stargazing with storytelling.

In the centuries-old Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, Princess Kaguya is a native of the Moon. In One Thousand and One Nights, Bulukiya travels the cosmos to other worlds. Johannes Kepler, a founding father of modern astronomy, wrote Somnium to popularize the heliocentric model of the solar system, and in it describes daemon-assisted space travel and a view of Earth from the lunar surface.

Even before we understood the staggering magnitude of the stars or the astounding true scale of the cosmos, the night sky activated within us a potent mixture of wonder and humility that has generated a spectrum of stories from fables to entire cosmologies. Staring at the sky has historically been a major driver of creative work.

Today, 56% of humans live in cities. Only 20% experience skies dark enough to see the stars undimmed by manmade light, with light pollution growing at a minimum of 2% each year—faster than the global population. This affects nearly all species on the planet from breeding sea turtles to blooming flowers to migrating birds; there is evidence that it affects human health. By the end of the decade, thousands more satellites will intrude on our remaining dark skies and could outnumber visible stars by a few tens to one.

This isn’t just a problem for astronomers. This is a problem for every human denied a birthright central to much of our artistic traditions.

The sky has always been a bottomless pool into which we have peered and tried to scry answers to our deepest, most vulnerable questions. We have tried to express these as treatises on the human condition, cautionary tales about human conceit, and extrapolations on near and future human achievement. On what mysteries can we reflect if the only thing the sky reflects now is ourselves?

As both an author and astrophysicist, I consider this question often.

I once went on a school trip to an observatory in Arizona. A few classmates and I found a hilltop where we lay on our backs and stared up at the countless stars stretching from horizon to horizon. I still remember the extreme vertigo of that moment when the sky felt not like a ceiling overhead but an endless chasm below into which I could fall if I didn’t grip the ground tight enough.

I once went on a school trip to an observatory in Arizona. A few classmates and I found a hilltop where we lay on our backs and stared up at the countless stars stretching from horizon to horizon. I still remember the extreme vertigo of that moment when the sky felt not like a ceiling overhead but an endless chasm below into which I could fall if I didn’t grip the ground tight enough.

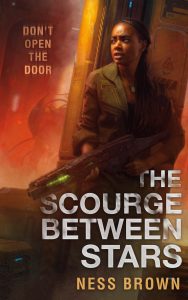

This disorientation, displacement of self, and decentralization of human experience is hugely important to speculative storytelling, and was a big influence on my debut science fiction novella, The Scourge Between Stars, which warns against human hubris in the realm of the heavens. In my novella, our species has recklessly compromised habitability on Earth and is stuck sailing the cosmos with no ability to make port (and things go from bad to worse when they discover they’re not alone onboard their ships). The sensation of being adrift among the stars that haunts the protagonist, acting captain Jacklyn Albright, is taken directly from my night on the Arizona hilltop.

Views like the ones I experienced are critically endangered, and their imminent extinction will undoubtedly influence the trajectory of human art.

The artificial cap of light pollution on the sky has cut us off from the natural amazement and discomfort that a glance at the grandness overhead brings. To maintain a healthy imagination, humans need that wonder. We need to reckon with what is still undiscovered. We need the visual confirmation that all the things we know can fit onto the surface of a small speck of dust suspended in space, and all the things we don’t yet know can fill the rest of the void.

That is what has long inspired us to put pen to paper and try to dream up the unknown ourselves.

Just as we must act against climate change and the degradation of our planet, we owe it to ourselves and future generations of storytellers to protect our dark skies. We should prioritize responsible lighting practices that serve our needs as a society while also preserving our view of the universe. This will ensure that one of our species’ greatest wells of creativity never runs dry.

We need to return the night sky to speculative storytelling.

Ness Brown was born and sort of raised in New Mexico, a land with long traditions of speculative storytelling and alien conspiracies. During their nomadic childhood, books became their vehicle to worlds unknown, which they continue to explore both creatively and as a career.

Ness came to New York City to study Astronomy at Columbia University, where they also found their husband and passion for Wing Chun kung fu. After graduating they spent six years teaching college astronomy and astrobiology, inspiring others to think about what or who else might be out there.

As an astrophysicist, Ness wonders about Cosmic Dawn and how the first generation of celestial objects affected the universe. As an author they wonder about how fantastical, horrific, and science-inspired stories affect us.

They are currently pursuing a graduate degree in Astrophysics with the help of their two cats, Mephi and Faust.

Dear Ness,

Thank you kindly for delivering such an informative, timely, and heartfelt message. I share your concerns. Corporations are littering OUR skies at astounding speed.

In a recent report, Auther Firstenberg, President of the international Cell Phone Task Force — an international coalition of scientists against littering the sky with satellites because of risks to Earth’s ecosystems and human health — reports the total number of operating satellites irradiating the Earth is currently about 8,800.

“The number of planned launches of low-orbit satellites now exceeds one billion…

“SpaceX has been sending up satellite-laden rockets every few days this year, in its haste to satisfy an insatiable demand for bandwidth by the billions of human beings who use cell phones. But SpaceX is not the only one. Hundreds of companies are competing for a share of the global market to supply Internet from the sky to the world’s population.”

And what about falling debris?

According to Wikipedia, “Space debris usually burns up in the atmosphere, but larger debris objects can reach the ground intact. According to NASA, an average of one cataloged piece of debris has fallen back to Earth each day for the past 50 years… Burning up in the atmosphere may also contribute to atmospheric pollution. Numerous small cylindrical tanks from space objects have been found, designed to hold fuel or gasses that has fallen off satellites due to collisions.”

And what about danger to space travel?

Isn’t any one of these concerns enough reason for NASA or our military leaders to halt the greed-grab before it’s too late?

Sincerely,

Robin Gregory

California

I apologize. There’s no edit button. Correction: “The number of planned launches of low-orbit satellites now exceeds one million…” Not one billion. Typo!