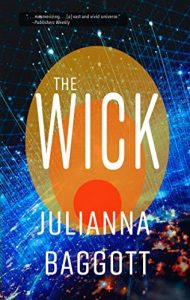

Caren Gussoff Sumption Reviews The Wick by Julianna Baggott

The Wick, Julianna Baggott (Underland 978-1-63023-068-5, $13.99, 100pp, tp), January 2023.

The Wick, Julianna Baggott (Underland 978-1-63023-068-5, $13.99, 100pp, tp), January 2023.

Julianna Baggott’s latest novella, The Wick, is a paradox: it’s short, abbreviated even, but also expansive. It’s utterly unlike anything I’ve ever read, but also, somehow, the lovechild of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go and Carol Emshwiller’s The Mount. It’s experimental and literary, making full use of the usually avoided second person point of view and present tense, but utterly readable.

It’s a wonderfully puzzling book.

Told in the voice of a hull named Bukef, a mostly organic, shape-shifting sentient creature built as a mech – a literal hardsuit to be worn for battle – The Wick opens on a space elevator. The elevator doubles as holding pen for both ‘‘defective’’ hulls like Bukef, who accidentally killed a wealthy young boy under the direction of his ‘‘wick,’’ or rider, and for decommissioned cachemes, or clones created as ‘‘backups’’ of children growing up in areas with high rates of mortality. Cachemes are only held as these backups until approximately age sixteen; after that, their memories get wiped and they are held in facilities like the elevator storage until they are repurposed as breeding wombs for the next generation of cachemes or sold into service as prostitutes. The fate of decommissioned cachemes, while grim, is better than what awaits Bukef and the other so-called defective hulls, who are held until they can be slaughtered and stripped for parts.

As Bukef waits for death in his pen on the elevator, a cacheme named Roon awakens in her glass cell. Frightened, thirsty, and confused, Roon bangs on her enclosure until she gains the attention of a guard who releases her. This is very lucky, indeed, because minutes later, the elevator is attacked, and Roon and Bukef find themselves dependent on one another for survival.

The convenience of the elevator attack’s timing – as well as a number of other suspiciously fortuitous timings throughout – are the weakest parts of the novella. I also found the immediate crowning of Roon, from the moment we meet her, as the ‘‘chosen one’’ (special, different than other cachemes, somehow able to immediately bond to Bukef in ways both emotional and physical) to be a little unbelievable. However, the emotional weight of the relationship that grows between Bukef and Roon and the artful contradictory nature of the novella’s construction makes those bits easier to swallow.

Together, Bukef and Roon escape to the surface of the planet below, a desolate, semi-apocalyptic wasteland of rust storms, war, and the carcasses of organic war machines that predate the development of the hulls. Through their bonding, Bukef can help Roon unblock some of her memories, and they realize this planet was once Roon’s home. To help her find out who she is, they decide to make a dangerous journey to find her home ‘‘ward,’’ which may or may not still exist.

As they travel, they run into a whole host of dangers, many of which, as I mentioned, are solved by a very luckily timed event, interloper, or accident. But through Roon, Bukef begins to develop some type of self-value beyond just being a war machine built to pair with a wick (yet another paradox, as Bukef’s sense of self grows stronger as they bond closer and tighter to Roon, in a collective ‘‘we’’ identity). But, this works, as do the other paradoxes that made The Wick so interesting.

Inside a hundred pages, Baggott manages to build a three-dimensional world. We are given snatches of its culture, well-curated bits that give us a window into the society there, deeply divided along class lines. She also provides insight into the planet’s history, as illustrated through the cadavers of generations of hybrids that litter the landscape. It’s amazingly robust, given the length.

Baggott embeds a number of gestural homages to other science-fictional works (for example, Bukef possesses some of the ethos of Emshwiller’s Charley, built for service, and Roon embodies the pathos of the clones at Ishiguro’s Hailsham. Even as the elegant, poetic prose is singularly Baggott’s, the nods to other literary genre works is a real treat. Lastly, Baggott’s use of the second person and the present tense adds the strangeness of a collective creature like Bukef and brings us close to him, as readers. The second person winds up feeling intimate, as intimate as the bonding between Bukef and Roon, and the present tense heightens the feelings of immediacy.

Even those who don’t tend to care much for literary science fiction will find The Wick a rewarding, emotionally charged read.

Caren Gussoff Sumption is a writer, editor, Tarot reader, and reseller living outside Seattle, WA with her husband, the artist and data scientist, Chris Sumption, and their ridiculously spoiled cat-children.

Born in New York, she attended the University of Colorado, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Clarion West (as the Carl Brandon Society’s Octavia Butler scholar) and the Launchpad Astronomy Workshop. Caren is also a Hedgebrook alum (2010, 2016). She started writing fiction and teaching professionally in 2000, with the publication of her first novel, Homecoming.

Caren is a big, fat feminist killjoy of Jewish and Romany heritages. She loves serial commas, quadruple espressos, knitting, the new golden age of television, and over-analyzing things. Her turn offs include ear infections, black mold, and raisins in oatmeal cookies.

This review and more like it in the June 2023 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.