Commentary by Cory Doctorow: The Swerve

If the bullies at the school gate steal your kid’s lunch money every day, it doesn’t matter how much lunch money you give your kid, he’s not gonna get lunch. But how much lunch money you give your kid does matter – to the bullies. Hell, they might even start a campaign: “The children of Jack Valenti Elementary School are going hungry! Congress must step in to give those kids more lunch money before they starve to death!”

There are five major publishers (maybe four, by the time you read this, depending on whether the FTC allows Penguin Random House to go ahead with its acquisition of Simon and Schuster). There’s one major national brick-and-mortar bookstore chain. There’s one major global ebook seller (which also sells more than 40% of all trade books, and sells nearly every trade audiobook). There’s one independent national trade book distributor.

Between them, these firms demand an ever-greater share of the wages of writers’ creative labor. Contracts demand more – ebook rights, graphic novel rights, TV and film rights, worldwide English rights – and pay less. Writers are expected to hustle more – on social media, on book blogs, on review sites – while publicity departments dwindle.

We’re the hungry schoolkids. The cartels that control access to our audiences are the bullies. The lunch money is copyright.

For 40 years, the scope and duration of copyright have monotonically increased, the evidentiary burden for copyright claims has declined, and the statutory damages for copyright infringement have expanded. Publishing and other ‘‘creative industries’’ generate more money than ever – and yet, despite all this copyright and all the money that sloshes around as a result of it, the share of the income from creative work that goes to creators has only declined. The decline continues. There is no bottom in sight.

The expansions in copyright are largely the result of lobbying by the entertainment industry, often with the help of high-profile entertainers, who are far more sympathetic than the corporations who are cheering them on. When Paul McCartney demands mandatory copyright filters that will algorithmically decide which words, sounds, images and videos can appear online, we find it easy to root for him – we all want the surviving Beatles to have a contented dotage. We’re far less likely to applaud the PR efforts of Universal Music Group, the world’s largest record label, whose revenues are divided among a rogue’s gallery of rapacious private equity firms and Chinese tech giants.

Universal is one of three major record labels. Its products are primarily aired on radio stations belonging to a single company (iHeartMedia). Its artists tour in venues mostly owned by a single company (Live Nation) and ticketed by another division of that company (Ticketmaster). They’re streamed on one of four platforms, but in reality, only one platform matters much – Spotify, which Universal has a substantial ownership stake in.

This pattern is the same in every entertainment and culture industry, from movies to TV to newspapers. Cartels and monopolies have erected chokepoints between creators and audiences. These chokepoints are a means to separate artists from whatever copyright powers the world’s legislatures have seen fit to give us. These copyrights – long-lasting rights to catalog, the power to remove others’ materials from the web – are turned into weapons that are used to clobber other parts of the supply chain and shift money from one firm to another (say, from streaming services to labels, or from publishers to ebook distributors), but no matter who wins a skirmish, creators lose.

You just can’t fix the bullies-at-the-gate problem by giving your kid more lunch money. No matter how ardently the bullies declare that their lobbying for more lunch money is about feeding your kid, we must understand that they are insincere.

How do we clear the bullies from the gate?

We need to restructure the market for artistic labor. Every policy we advocate for must be in service to this principle: so long as we are feeding our work into a supply chain whose every link is monopolized, we cannot thrive. Our labor interests demand the de-monopolization of the artistic industries, from investors like publishers and studios and labels, to distributors, to retailers.

Last year, I worked with the Australian copyright scholar Rebecca Giblin to write a book that describes in eye-watering detail how the monopolized parts of the entertainment industry misappropriate the wages of creative labor. More importantly, fully half of our book is devoted to laying out detailed, technical proposals for unrigging creative labor markets.

The book is called Chokepoint Capitalism: How Big Tech and Big Content Captured Creative Labor Markets and How We’ll Win Them Back, and it came out from Beacon Press in late September. Our goal is to break the foolish deadlock that invites creators to root for Team Big Tech or Team Big Content in the hopes that whichever giant emerges triumphant will dribble a few more crumbs for us.

I won’t rehearse all of our proposals here – you can read the book for that – but I’ll give you an example of one laser-focused intervention that would produce immediate, profound financial relief for artists of every kind, all over the world.

Most artistic contracts include a clause permitting creative workers to audit their royalty statements. However, settlements arising from these audits are typically bound by nondisclosure agreements. That means that if you discover that your publisher, label, or studio is ripping you off, you might get them to cough up the money they owe you – but only by promising not to tell similarly situated creators where they should look for the money that’s been stolen from them.

But nearly all artistic contracts are bound by the laws of three states: California, New York, and Washington (because Amazon). Passing short bills in all three states that make nondisclosures non-enforceable when they refer to funds misappropriated through funny accounting would, at the stroke of a pen, instantly put millions of dollars into artists’ pockets.

We spoke to creators who’d found six-figure accounting frauds in their royalties. They spoke on condition of anonymity and wouldn’t tell us where other creators should look to recover their own stolen fortunes. Indeed, we spoke to many people who’d audited their royalty statements – and not a one of them found an error in the creator’s favor. Without fail, every accounting ‘‘error’’ benefits a multinational, monopolistic entertainment company.

This is inevitable: the bullies at the gate aren’t content with taking your lunch money. Once they have you where they want you, they’ll take everything. It’s past time we recognized that improving the fortunes of creators starts with separating their interests from the interests of the corporations we bargain with. Once we understand that fundamental fact, we can start designing reforms and even revolutions that help creators eat, pay their mortgage, and fund their retirement.

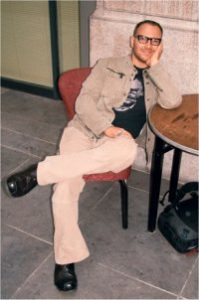

Cory Doctorow is the author of Walkaway, Little Brother, and Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free (among many others); he is the co-owner of Boing Boing, a special consultant to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a visiting professor of Computer Science at the Open University and an MIT Media Lab Research Affiliate.

All opinions expressed by commentators are solely their own and do not reflect the opinions of Locus.

This article and more like it in the November 2022 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.

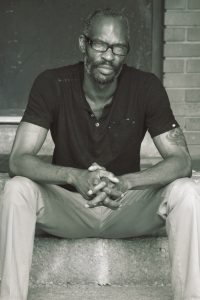

One of my best mates is an actress on a popular soap opera. When she audited her account, there were numerous errors and not a single one of them were in her favour. She was out to the tune of thousands due to ‘errors’.