Charles Payseur Reviews Short Fiction: Strange Horizons, Hexagon, and Diabolical Plots

Strange Horizons 5/16/22, 5/23/22, 5/30/22, 6/6/22

Strange Horizons 5/16/22, 5/23/22, 5/30/22, 6/6/22

Hexagon Summer ’22

Diabolical Plots 6/22

Finding a poem by R.B. Lemberg is always reason to celebrate, so I was cheering when I came across their latest in May’s Strange Horizons. “The broken hill and the breath” is a powerful piece about long cycles of harm and healing, about a grove of fruit trees and a fragile peace unfolding around disaster and damage. The piece seems to me to be linked to Lemberg’s upcoming novel, The Unbalancing, but even without that added layer of meaning the poem remains deep and satisfying, showing how peace can be shattered, and how it can remain whole all the same. Remaining on the poetic side of things, Yee Heng Yeh’s “Lost and Found” bridges speculative and non-fictional elements by focusing on 17 unclaimed bodies, victims of COVID-19. The verse treats with collective loss, speaking to those who might claim these bodies while exploring what it means for the unclaimed whose stories seem cut short. The piece reveals a tragedy that seems in part an accusation left for the living, who stumble in knowing what to do in the face of such loss and unnamed sadness.

May also brought a special visual arts issue of Strange Horizons, featuring some stories that were commissioned based on works of visual art (rather than the more traditional other-way-round). It also featured a couple of graphic stories, including “When They Sank” by Fernanda Castro & Sunmi. It’s a story of first contact, though not the kind normally portrayed: this is a meeting (of sorts) between mer-people and humans, set in the age of sailing ships. The art paints a murky picture of the meeting, grisly and graphic. The darkness on the screen is a heavy presence, with light and dark contrasting like the beauty and grotesquery of the scene. The other graphic story, “Which One Is Meat” by Nadia Shammas & Isabel Burke, similarly plays with shadow and light, with contrast and similarity. In it, twins are a gift from the world, one that requires a sacrifice. The work builds tension masterfully, showing how difficult it truly is to see even animals as just meat when you live with them every day and watch them grow – and how potent the sacrifice is to give up something that is loved. Shammas and Burke use the writing and art to twist a knife in the hearts of readers, mixing horror and hope to brutal effect. Moving out of the special issue, and June brought with it Michelle Kulwicki’s “Bee Season”, a story of Ash and Min – two young women growing in a world devastated by climate change. They feel trapped in their town, in their families, in the roles expected of them, and their defiance and rebellion take the form of wanting to escape to the Garden, the last green place on the planet. Entry, however, is not free, and the story shows the transformations required to find the way there – some of the body and some of the spirit. Kulwicki shows the tension of hope and disappointment acting like a wedge between the characters, their love of each other strained by their need to escape from a place without a future. The result is something difficult and messy but also vibrant and alive and amazing.

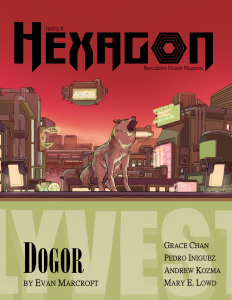

June’s Hexagon features science fiction stories mostly exploring futures where current trends have led to rather grim outcomes, where a focus on maintaining comfort in the face of increasing natural destruction doesn’t do enough to actually prevent the situation deteriorating further. Tucked into that, though, there’s also a strong focus on animals, and on designing them. It comes up first with Mary E. Lowd’s “Build-a-Pet”, where a child desires a pet that they create, that they shape in an arcade like a toy. The story understands wanting something, and how that child-like want can look past the chilling implications of technology and focus instead solely on ownership, filling a perceived lack that not even the flashiest of designer pets can fill. It’s a theme further complicated in “Working Overtime at the Kludge Factory” by Andrew Kozma, which finds Harlow working to try and fill the gaps left by extinct or soon-to-be extinct animals. It’s a project the government mostly supports, not because it has much hope in stemming the catastrophes of species loss and ecosystem collapse, but because it’s a reactive rather than proactive approach to environmental protection. It does not seek to save species, but instead treats their loss as a kind of inevitability, which makes the cause of those extinctions unimportant. I deeply appreciate how the story shows the fiction of control that Harlow lives surrounded by, the same that robs climate change of its urgency and humanity of its agency. It’s a grim story, sharp in its observations and merciless in its honesty.

Pets return to the forefront in the issue’s final story, Evan Marcroft’s “Dogor”. In the tale, Marcroft introduces Marisol, also known as the influencer TruceHurts, in a future where certain species are being brought back from extinction. The goal is not to fill keystone roles in ecosystems, though. Rather, it’s to do public relations damage control for corporations who have devastated parts of the world. What better way to wash a reputation clean of blood than with a previously extinct designer puppy? Marisol is only too glad to help, at least at first. But as the nature of the canine that she takes in begins to become clear, she begins to understand the system she’s a part of a little better, seeing how humanity only keeps species that it finds useful, and quickly or slowly destroys everything else. It’s a moving work, and Marcroft does a great job avoiding trite messages, instead lingering on the messy ways people live messy lives, and how part of that mess is designed by those invested in the status quo, and part of that mess is just people being compassionate, imperfect beings.

Diabolical Plots released three stories in June rather than their normal two, and overall the issue leans a bit melancholic and haunting. That is, except for Sarah Pauling’s irreverent “Timecop Mojitos”, which unfolds from the point of view of the roommate of a historian who might have kind-of stolen a time-bending cave claimed by a guild who is rather protective of the military advantage the cave gave them. It’s a complex premise but tempered by an enthusiastic and eager voice and a casual flippancy that makes even the most outlandish of speculative elements seem less interesting than finally scoring a decent date. Pauling manages a loose energy that breathes new life into a rather pulp-infused and “classic” idea of time cops out to protect their own status quo rather than allow their power to fall into the hands of… nerdy historians. A delightful read.

Recommended Stories

“Bee Season,” Michelle Kulwicki (Strange Horizons 6/22)

“Dogor,” Evan Marcroft (Hexagon 6/22)

This review and more like it in the August 2022 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.