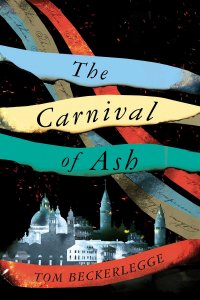

Paul Di Filippo Reviews Tom Beckerlegge’s The Carnival of Ash

The Carnival of Ash, Tom Beckerlegge (Solaris 978-1786185006, hardcover, 528pp, $24.99) March 2022.

The Carnival of Ash, Tom Beckerlegge (Solaris 978-1786185006, hardcover, 528pp, $24.99) March 2022.

Some modes of fiction can start to appear dead or at least quiescent, until a certain writer comes along, gives them a shake, and infuses new life into the somnolent corpus. Such has just happened with Tom Beckerlegge’s first novel for adults (as Tom Becker he has had a sterling career producing YA books), With The Carnival of Ash, he has reinvigorated the Ruritanian tale, thus joining the ranks of Le Guin (Orsinian Tales), Aldiss (The Malacia Tapestry), Davidson (The Enquiries of Doctor Esterhazy), and many others.

If you visit the entry for “Ruritania” at the Science Fiction Encyclopedia, you will get a very handy rundown of the history of this fascinating subgenre which, basically, relies on the creation of an imaginary country coterminous with consensus geography. In Beckerlegge’s instance, it’s an imaginary city in a real country, but I think he qualifies by the SFE test: “Only two elements are essential: the tale must provide a fairy-tale enclave… located both within and beyond normal civilization; and it must be infused by an air of nostalgia….”

(And if we can indeed apply this test to standalone cities, don’t all those imaginary burgs in the DC comics universe—Metropolis, Gotham, Central City—qualify too? An intriguing twist on the superhero mythos.)

In the case of this book, the locus of irreal novelty is the Italian town of Cadenza, late in the 1400s, early 1500s. (Savonarola is a contemporary figure mentioned.) Located somewhere south of Venice (its major rival, unto the point of open warfare), Cadenza is unique in that it is a city devoted to poetry, literature, playwriting, and other wordful arts. Full of libraries both public and private, it features, of course, a deep stratum of average citizens who work in other trades, but also tons of artists, as we shall see. Even their politics and ruling class are infused with poets.

We open with a comic scene. A hungover, despairing poet lies in an open grave, refusing the entreaties of the gravedigger, Ercole, to vacate the premises, where an actual corpse has prior claim. The living intruder is young Carlo Mazzoni, come to Cadenza to make his reputation and uphold his family’s honor. Unfortunately, Carlo is not as talented as he imagines, and he is facing a deadly local web of Machiavellian intrigue that he can’t begin to imagine. When he introduces himself to Count Lorenzo Sardi, a potential patron, all his plans go into the rubbish, although he does make a friend with one of Sardi’s clique, a fellow named Raffaele. He also meets the lovely Hypatia, the most famous “ink maid.” These women earn their living by writing any imaginative texts to order for their clients that will slake the passions. (Cue Anaïs Nin and Delta of Venus here.) By the end of the first chapter (or “Canto”), Carlo is reduced to living with Ercole and trying to resurrect his dreams.

And along the way, we have also been deftly given much backstory about Cadenza, with more to come in other chapters. The richness and outré nature of this history is a large part of the book’s pleasures.

Now, I assumed at this point that we would be following Carlo’s POV consistently henceforth, providing a kind of A Confederacy of Dunces, Italian-style. But Beckerlegge has a much more innovative pattern in mind. For the next ten chapters, we will inhabit each the world of a different protagonist. Faces familiar from earlier will reappear, of course, but not as the main doers. Then, when we get to Canto Twelve, all the threads will be beautifully, suspensefully, surprisingly tied up, as we flit from viewpoint to viewpoint, but with Carlo returning strongly.

Canto Two revolves around the life of Hypatia, and its title “The Letter O” alerts us to its parallels with The Story of O. Yes, the YA writer named “Becker” has been put aside for the very adult fellow named Beckerlegge, who is going to focus on many mature topics: sex, treachery, art, ambition, torture, insanity, death.

Next up we become intimate with Lorenzo Sardi, feeling his age and lack of certainty, despite all his worldly trappings. The Fourth Canto looks in on Cosimo Petrucci, the Artifex or ruler of Cadenza. Something of a usurper, he’s a nasty piece of work, and his actions go a long way towards bringing on the eventual doom of the city.

The fifth chapter involves a nameless “I” in search of the legendary lost original library of the city’s founding. Next up is a great Umberto-Eco-style self-contained mystery featuring a detective monk, Fra Bernardo. Following that, we meet Hypatia’s sister, Maddelina, a kind of tomboy bruiser in contrast to Hypatia’s erotic delicacy. She gets involved in a situation akin to “The Ransom of Red Chief.”

It should be mentioned that throughout all these individual tales, the macroscopic plight of the city is continually evolving, heading plainly towards a bad destination.

The hell really begins in the next Canto with the arrival of the plague. Our viewpoint here is a scholar named Aquila, met previously. “The Masque of the Red Death” comes to mind in the next chapter, set at the “plague party” in the villa Orsini. Canto Ten restores humor as a major component (the book is plentifully provided with same throughout) by telling of the siege that a hired military man, Stefano Pellegri, conducted—against a tower occupied only by a beautiful woman and her servant! The eleventh iteration looks in on the nunnery of the Sisters of San Benedetta, where all the nuns have had their tongues removed. And then, at last, comes the grand climax, replete with death, destruction, and some not-unhopeful outcomes for several of the wiser and more lovable folks.

The zest and wit that Beckerlegge infuses into his fantastical Decameron is marvelous, carrying the reader from one incident—thrilling, outrageous, tender, ironic—to another without pause. Cadenza is as tangible as Paris or London, its history overstuffed with Gothic goodies. The human interactions cover the entire spectrum of Homo sapiens’ doings, from highest to lowest. In short, The Carnival of Ash is a Rabelaisian-Calvinoesque outing that should appear on the World Fantasy Award ballot—or my Italian heritage will be vastly insulted!

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.