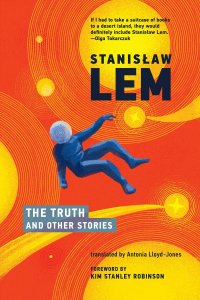

Paul Di Filippo Reviews Stanisław Lem’s The Truth and Other Stories

The Truth and Other Stories , Stanisław Lem (The MIT Press 978-0262046084, 344pp, $39.95) September 2021.

The Truth and Other Stories , Stanisław Lem (The MIT Press 978-0262046084, 344pp, $39.95) September 2021.

“Of these twelve short stories by science fiction master Stanisław Lem, only three have previously appeared in English, making this the first ‘new’ book of fiction by Lem since the late 1980s.” Thus reads the press release accompanying this hot-off-the-presses volume (from a somewhat unlikely source, MIT Press), a plain and sober statement of fact. And yet that sentence should probably be written in all-caps of a gargantuan font size. This is a treasure-rich discovery akin to finding an unpublished novel by Sturgeon, some heretofore-unseen Hainish stories by Le Guin, or maybe a lost mainstream manuscript by Philip K. Dick. (I ring in PKD here ironically, given the weird imbroglio between him and Lem, which you can read about here.)

Nor are these stories mere juvenilia or toss-offs or unfinished pieces. They represent solid, finished, accomplished primo Lem from 1956 to 1993. Again, what a miraculous find!

Before delving into the tales (I hope to adduce Lem’s virtues and effects afterwards), let me shower some non-Lem praise on Kim Stanley Robinson’s lucid, insightful and intimate introduction (“[Lem’s] characteristic voice, both calm and intense, magisterial but monomaniacal, even crazed, becomes ultimately what one might call passionately rational…”), and also on the astonishingly magical translating powers of Antonia Lloyd-Jones. Perfect companions to Lem’s prowess.

“The Hunt” is told from the POV of a being who has been set loose with a head start prior to a band of human hunters coming after him for the slaughter. Gradually—and this is not much of a spoiler—we realize our quarry is a sentient robot. The pathos here is matched only by the cinematic propulsiveness and the conjuring of a silicon mentality. (I had fun imagining the bot as one of the famous creations from Boston Dynamics!) Watch for the bitter sting of betrayal at the end.

A huge unknown hulk crashes to Earth. Two human passersby are engulfed by it, like Jonah by the whale. They spend the whole story dealing with the unknowable alien interior, at peril of their lives. This is “Rat in the Labyrinth,” and it harks to tales like Phil Farmer’s “Mother” or even Budrys’s Rogue Moon.

“Invasion from Aldebaran” is the silliest entry, a lot of Twilight Zone fun, recounting the explorations on Earth of two hapless aliens (“…springy twigs lashed at their cuttlefishy heads…”) as all their advanced tech is undone by human cussedness.

Poor Mr. Harden, such a nebbish. Not very successful at life. Until he follows some mysterious plans given to him by “a friend” and builds a machine he dubs “the conjurator.” It puts him in touch with an entity who plans on doing— But I’ve revealed enough about “The Friend”.

Harking to Wells’s classic, “The Invasion” finds a series of pods striking the Earth from space and maturing to surreal alien capacities. Scientists are baffled, the military is aggressive (in almost comical Toho Studios fashion). But just when one expects a full War of the Worlds scenario, Lem pulls the carpet out from under the reader. Also, please note here the pure beauty and power of Lem’s naturalistic opening paragraphs, which read like something from D. H. Lawrence.

Greg Bear’s Blood Music is an appropriate yardstick with which to measure “Darkness and Mildew”, which chronicles the invention of an entropic plague. And when the inventor accidentally ingests some… Well, Lem does not balk at following every path to its logical end.

Half of “The Hammer” is told in pure dialogue, as a machine intelligence unburdens itself of its phobias to an interlocutor. (Consider Gerrold’s When HARLIE Was One as a cousin tale.) The other half concerns a one-man mission to the stars where the tool of the title comes dramatically into play.

“The Nine Billion Names of God” resonates with “Lymphater’s Formula,” except that Lem has much to say about the blind drives of evolution, and how humanity could be in the process of dethroning itself from the apex of creation.

“The Journal” is a very dense but never boring philosophical tract presented in the words of a being that considers itself both omniscient and omnipotent. We learn its identity only in the final pages.

Scientists seeking to tame solar-level masses of plasma accidentally unleash a new kind of life in “The Truth”.

I could imagine Simak, with his background in journalism, writing “One Hundred and Thirty-Seven Seconds”, in which a rough-and-tumble newspaper guy, in charge of a super-sophisticated newsroom computer, discovers that his machine can predict the future—under very bizarre circumstances. And in this 1976 tale, Lem seems to have predicted that noxious software known as Autocorrect:

Indeed, the IBM 0161 is not a passive transmitter; if the teleprinter supporting it makes a spelling or grammatical mistake, the error appears on the screen, to be replaced at lightning speed by the correct form of the word. Sometimes this happens so fast that you don’t notice it, and you only find out that a correction has been made when you compare the typed-out text with the one the computer has put on screen.

Lastly comes the highly amusing jape “An Enigma,” in which robot priests thrash out the heresy involving squishy life.

The first of Lem’s characteristics I’d like to cite might not be obvious: his kinship with Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith and Thomas Ligotti. The notions of HPL & Company about how humanity is a mote in an uncaring universe full of strangeness finds no more deft disciple than Lem. “The Friend” for instance might be the brother to “The Whisperer in Darkness”, while “Rat in the Labyrinth” echoes Smith’s “Seedling of Mars”, in which some stray humans are inveigled aboard a Martian ship. This cold, calculating perspective on humanity’s ultimate insignificance and bafflement in the face of cosmic majesty is a linchpin of Lem’s work.

Also, while he can be incredibly visual and tactile and plot-driven, as in “The Hunt”, he is not afraid to utilize SF’s peculiar narrative modes, doing big info-dumps, as in “Lymphater’s Formula”. The naked discursiveness of “The Journal” is a fine example of Lem’s daringness in pushing the limits of what a “story” means.

Unlike Cixin Liu, another non-Anglo SF guy, Lem seems not much of a believer in organizations or mass efforts. His protagonists are all loners, eccentrics, more in line with many American heroes.

And finally, Lem’s wry, black humor cannot be denied. This volume does not include anything as hilarious as The Cyberiad or The Futurological Congress, but a bright thread of laughter runs throughout.

MIT Press deserves immense kudos for getting out this volume, which surely represents some of the best SF of 2021—despite being decades old!

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.