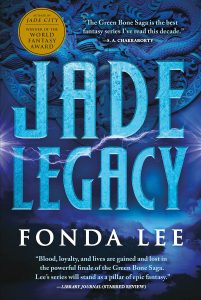

Fonda Lee Guest Post–“We Can’t All Be Optimus Prime: Portraying Organizational Leadership in Fiction”

Who’s the best fictional leader?

Optimus Prime? Jean-Luc Picard? Captain America?

I’m willing to wager that all three of those iconic characters would be among the most popular contenders if the question were asked in a general poll, and for understandable reasons. When I was ten years old, sitting in front of a television set on a Saturday morning, Peter Cullen’s voice as Optimus Prime ordering, “Autobots, roll out!” made me vibrate with the desire to transform myself into a Honda Civic and roll the hell out for Optimus. And Captain Picard set the standard for an entire generation of science fiction fans by portraying a starship captain who epitomizes diplomacy, dignity, decisiveness, intelligence, and integrity (not to mention the good sense to not shag every single alien babe that the Enterprise encounters in its adventures).

Many memorable fictional leaders, especially in speculative fiction, play well on screen. They have presence. They’re extremely good at giving motivational speeches. They’re courageous, wise, inspirational, and can often handle themselves in a fight, charging into battle ahead of their loyal followers. The vast majority of us have never worked under a boss who reminds us of say, Steve Rogers, and most of us, even if we were given years of management training and coaching, can never approach emulating the leadership styles we most admire in SF/F novels and movies.

I have perhaps a slightly different approach to depicting leadership in fiction. Graduating with an MBA from Stanford University and spending a decade in business, first as a management consultant and then as a corporate strategist, I went through a lot of classes on organizational leadership and leadership training. I’ve managed people and teams (this is not to say I was especially good at it; I quit that career to sit by myself and write fantasy novels all day, so take that for what you will). I’ve worked under a lot of highly accomplished business leaders. I’ve reported directly to VPs and sat in boardrooms with CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, preparing them for investor meetings. The one overriding observation from those experiences that I’ve applied to the stories I now write—regardless of the fact that they take place in secondary worlds with magic, or far futures with advanced tech—is that there is no one best way to lead. There are many styles of leadership, and most of them are not inherently good or bad. (Well, maybe Darth Vader’s Force-choking of subordinates is bad.) Different approaches have benefits and drawbacks and may be more or less effective in different circumstances and organizations.

The Green Bone Saga, my epic fantasy trilogy that began with Jade City, continued in Jade War and concludes this November with Jade Legacy, is chock full of characters in positions of leadership. The Green Bone warriors who wear and wield magical jade are the highest status members of their society, and the protagonists of the story, the Kaul family, are the leaders of one of the largest Green Bone clans in the island nation of Kekon. They are responsible for running an organization with tens of thousands of people, from street enforcers to international lawyers, and they deal with numerous stakeholders—businesses that pay them patronage, tributary entities, politicians in the government, and foreign officials, to name a few.

The Green Bone Saga, my epic fantasy trilogy that began with Jade City, continued in Jade War and concludes this November with Jade Legacy, is chock full of characters in positions of leadership. The Green Bone warriors who wear and wield magical jade are the highest status members of their society, and the protagonists of the story, the Kaul family, are the leaders of one of the largest Green Bone clans in the island nation of Kekon. They are responsible for running an organization with tens of thousands of people, from street enforcers to international lawyers, and they deal with numerous stakeholders—businesses that pay them patronage, tributary entities, politicians in the government, and foreign officials, to name a few.

I’ve spent years describing the series to potential readers as a story about family, honor, clan warfare, tradition versus modernity, and badass wuxia-style magic-fueled knife fights.

It’s also a story about leadership and organizational change.

Every single one of the main characters becomes a leader in their own way—some are thrust into the role suddenly, others seize it willingly and with force, others grow into it slowly. They all struggle with the same challenges that I’ve studied in school, observed managers dealing with, and experienced myself—balancing competing interests, exerting influence, delegating, motivating others, disciplining those who fail the team, becoming confident in their own abilities and playing to their strengths, and leaning on trusted allies to mitigate their weaknesses.

Since the trilogy spans nearly thirty years, different characters occupy the same role, and each does so in their own way. In the clan hierarchy, the Horn is the top military leader in the clan, a fearsome warrior expected to carry a whole lot of jade. It would easy to write the character of the Horn using the blunt stereotypes we already have for men in violent professions, or by leaning on fictional depictions of mob enforcers: tough guys, emotionally stunted muscle men who aren’t terribly bright but who can be trusted to get the job done when there are skulls to be cracked.

What’s far more interesting to me, however, is writing different characters (each of whom, to be clear, meets the necessary job requirements of skill in skull-cracking) bringing their own personal stamp to the role and succeeding in their own way. The first Horn we meet in Jade City, Kaul Hilo, is a natural people person, someone who cultivates relationships with street charisma. The next man who takes on the role, Maik Kehn, is a man of few words, a stoic commander who’s tough but fair. His successor, Juen Nu, is an operational mastermind who sets about improving his organization’s capabilities, distributing responsibility, and making the clan far more nimble and efficient. And the fourth Horn in the series (who I won’t name so as not to spoil the final book) is a pragmatic, reliable insider who leads by hardworking example.

When I was in business school, I recall there being quite a bit of discussion about supposed differences between the leadership styles of male versus female executives, as well as how male and female leaders are viewed differently by subordinates and peers. Men, some management scholars claimed, are more authoritative, hierarchical leaders who focus on goals and tasks, while women managers, they said, tended to be relational leaders who prioritized people and team cohesiveness. Others challenged these theories. Was this really an innate difference between men and women, or was it that women with authoritative styles were viewed negatively, and so female managers learned to lead in “softer” and more diplomatic ways in order to succeed?

Whatever the truth, the fascinating intersection between gender and organization leadership influenced one of the biggest character decisions I made early on in the series. The leader of the Mountain clan, Ayt Mada, is a farsighted strategist who employs a classic command-and-control style of leadership, one that moves the entire organization toward her vision, akin to the autocratic style with which Steve Jobs ran Apple for decades as he built it into one of the biggest and most recognizable brands in the world. Her rival, Kaul Hilo, in contrast, is an emotionally oriented leader who prioritizes connection and friendship with the many individuals who follow him out of personal loyalty. He leans heavily on the advice of his inner circle, including his sister and wife. George H.W. Bush was said to have a similarly relational style of leadership.

In a fantasy series filled with assassinations and backroom dealings, honor duels and sudden deaths, I gave the woman the more accepted “male” leadership style and the man the supposedly more “female” leadership style. I wanted to create a cast of characters that invited contrast and comparison, that showcased both male and female leaders employing a range of approaches to wielding power and exerting influence. I wanted to show people who weren’t “born leaders” being unprepared for their roles but nevertheless growing into their jobs. I wanted to demonstrate that even good leaders can be undone by circumstances outside of their control, and that often the success of a group depends on having the right leader at the right time, someone capable of steering an organization through specific challenges and adapting to inevitable forces of change.

I wanted my characters to feel like people I could’ve studied in business school.

Here’s my suggestion to writers: The next time you’re about to write a starship captain, an army commander, a chosen hero, or anyone else who must shoulder leadership, don’t ask, “How do I write a leader?” Instead, create a fully realized character, someone with their own temperament, outlook, strengths, and blind spots, and then ask, “What kind of leader can they learn to be?”

Fonda Lee is the World Fantasy Award-winning author of Jade City and the award-winning YA science fiction novels Zeroboxer, Exo, and Cross Fire. Born and raised in Canada, Lee is a black belt martial artist, a former corporate strategist, and an action movie aficionado who now lives in Portland, Oregon with her family.