Lavie Tidhar: Between the Cracks

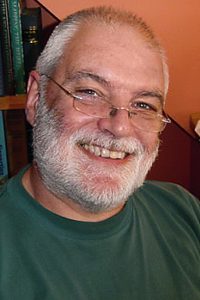

LAVIE TIDHAR was born November 16, 1976 and raised on a kibbutz in Israel. He has traveled extensively since he was a teenager, living in South Africa, the UK, Laos, and the small island nation of Vanuatu.

Tidhar began publishing with a poetry collection in Hebrew in 1998, but soon moved to fiction, becoming a prolific author of short stories early in the 21st century. Story “Temporal Spiders, Spatial Webs” won the 2003 Clarke-Bradbury competition, sponsored by the European Space Agency, and “The Night Train” (2010) and “New Atlantis” (2019) were Sturgeon Award finalists. Vampire mystery “Judge Dee and the Limits of the Law” (2020) is currently a finalist for the Eugie Foster Memorial Award.

Linked story collection HebrewPunk (2007) contains stories of Jewish pulp fantasy. Some of his other short fiction has been collected in British Fantasy Award finalist Black Gods Kiss (2014) and The Lunacy Commission (2021).

He co-wrote dark fantasy novel The Tel Aviv Dossier (2009) with Nir Yaniv. The Bookman Histories series, combining literary and historical characters with steampunk elements, includes The Bookman (2010), Camera Obscura (2011), and The Great Game (2012).

Standalone novel Osama (2011) combines pulp adventure with a sophisticated look at the impact of terrorism. It won the World Fantasy Award and was a finalist for the Campbell Memorial Award, a British Science Fiction Award, and a Kitschie.

His other novels include Martian Sands (2013), The Violent Century (2013), British Fantasy Award finalist A Man Lies Dreaming (2014), Clarke Award finalist and Campbell Memorial Award winner Central Station (2016), Campbell Memorial Award finalist Unholy Land (2018), By Force Alone (2020), and The Escapement (2021). His take on Robin Hood, The Hood, is forthcoming this fall.

Much of Tidhar’s best work is done at novella length, including An Occupation of Angels (2005), Cloud Permutations (2010), British Fantasy Award winner Gorel and the Pot-Bellied God (2011), Jesus & the Eightfold Path (2011), and The Big Blind (2020).

Tidhar advocates bringing international SF to a wider audience, and has edited The Apex Book of World SF (2009), The Apex Book of World SF 2 (2012), and The Apex Book of World SF 3 (2014); he was editor-in-chief of the World SF Blog from 2001-13, and in 2011 was a finalist for a World Fantasy Award for his work there. He launched The Best of World SF anthology series in 2021, with more volumes to come.

Tidhar edited A Dick and Jane Primer for Adults (2008) and co-edited Jews vs Aliens (2015) and Jews vs Zombies (2015) with Rebecca Levene; wrote Michael Marshall Smith: The Annotated Bibliography (2004); wrote picture book Going to the Moon (2012, with artist Paul McCaffery) and children’s book Candy (2018); and scripted one-shot comic Adolf Hitler’s “I Dream of Ants!” (2012, with artist Neil Struthers) and the 5-issue comic Adler (2020, with artist Paul McCaffrey). He writes about SF for the Washington Post.

Tidhar lives in London.

Excerpt from the interview:

“The problem I have is I keep falling between the cracks. Even ten years ago – was Osama really a fantasy book? And the books I did after Osama. Is A Man Lies Dreaming a fantasy or a literary novel? I seem to keep falling between the cracks: people who like genre don’t like what I’m doing with genre, and the people who like books about the Holocaust or about WWII or about terrorism don’t want any fantasy dressing on it – they don’t want the weird stuff. For a long time, with every book I’ve tried to write, I’ve wanted it to mean something. Unholy Land is a very political book about nationalism and borders and Israel and Palestine, but it’s got Lovecraftian jokes thrown in and Zelaznyesque moving between worlds, and it’s a mixture of genres. My biggest struggle is that my books don’t fit anywhere. They don’t fit for the people who like their dragons to be dragons and their elves to be elves, and they don’t fit for the people who don’t want dragons or elves at all.

“At the moment I’m falling between the cracks instead of expanding. That’s why I thought doing something without elves and the aliens might be useful. I also just want to write the books I want to write. I’ve had editors say to me, ‘You have to change your name, if you’re going to do a literary novel,’ or if I do a literary novel – A Man Lies Dreaming came out as a literary novel in the UK – they’ll say, ‘You can’t go from that to a science fiction book.’ I said, ‘My next book has a spaceship on the cover!’ But the nice thing is, I’ve made myself this spot, however small it is, where I can go and write a children’s book or a graphic novel or a science fiction book or a mainstream historical epic, and I get to keep my name. I’m the only one who has my name. If your name is Steve King, there’s a hundred Steve Kings, and I’m sure the world wouldn’t mind if one of the Steve Kings changed their name to Bob. But I don’t have that luxury.

“I’m very lucky to be publishing books. I never thought that I’d be a full-time writer for ten straight years. That seems crazy. All I had to do was give up my life and any sort of material comfort. I’m kidding! It’s very rare to be able to keep publishing books at all in this industry, where you get one chance and then you’re out.

“Osama was rejected by every publisher under the sun, and now it’s getting a tenth anniversary edition in the UK from Head of Zeus. I said, ‘I need to have a tenth anniversary edition. You want a book that looks like it deserves a tenth anniversary edition.’ In those ten years I’ve tried to make sure that every book I write is a book that means something. It isn’t just there to sell books, or because I’m contractually obliged. I never wrote to contract – I only wrote the books I wanted to write. My agent John would tear his hair out and say, ‘I don’t know what to do with it,’ but somehow it’s worked. In a small way, it’s worked.

“A lot of it is a fight with publishers to keep the books going, and again, I’ll give John credit for fighting really hard. I’m lucky in part because I found Head of Zeus in the UK, and they have been very open to doing some of the stuff that I’ve wanted to do for a long time, including those Best of World SF anthologies. I spent at least a decade banging on publishers’ doors asking to do a book like this, and either just being told no or getting ghosted.

“I edit by reading widely, so I read the stories first and I know what’s out there, and then I just ask for them when I want them in a book. This time around, because I’m sort-of editing volume two, I just approached a handful of writers and said, ‘Will you write me an original story?’ I thought of doing a whole original anthology and then started hyperventilating, and I thought, ‘Oh, no no no.’ But there was there was this one writer I found who writes dark fantasy that I thought was really good, and I emailed them and I said, ‘Will you try writing a science fiction story?’ They’d never done one before. I was really happy with that.

“I’ve never been hugely happy with Martian Sands. It was an early attempt at working with some ideas. A long time ago, I wrote a sequel to Martian Sands that wasn’t very good, so I’ve never done anything with it, but I’m making an animated webseries at the moment about a toaster and a coffee machine in a kitchen on Mars. At the moment it’s called Mars Machines. The series draws on Martian Sands and on that unpublished novel. My friend Nir is doing the animation. I wrote a couple of books with him, and when he started doing animation, I said, ‘Let me write you something with an actual story – one of the reasons it’s a toaster and a coffee machine is because he can’t draw people. I was like, ‘Let me make it as simple as possible.’ We got some voice actors and we’re four episodes down, out of seven in total – we’re going to keep at it until it’s finished and then try and find someone crazy enough to sell it to.

“For fun I’ve been doing games. I teach myself things as a hobby – I don’t know why. I started teaching myself how to make mobile games for Android and stuff, and so The Escapement is going to have a mobile game out alongside it. It’s a side-scrolling game, so you play a cowboy riding across the Escapement shooting at gunmen and balloons and picking up objects. There’s a little animated opening. I’m just stuck on a bug – basically making games is all about bugs. But you have to learn, and there’s a whole ecosystem online for game assets – the music, sound effects, animation, drawings. You listen to a lot of squelching sounds. I’m having to use a lot of free stuff, or modifying existing things. It’s really interesting, but incredibly time-consuming.

“In December 2020 we realized there was going to be another lockdown coming and it absolutely killed me. I couldn’t get anywhere on that big novel I was working on, and I started writing another science fiction book set in the Central Station universe. I basically just had this image of a robot picking up a flower. I didn’t know what this robot was doing or why it was picking up a flower, so I started writing it as a little short story, and that didn’t really answer the question. So I wrote another story to see what would happen, and the robot was digging things up in the desert at that point, which just opened up more questions. Before I knew it, I had my lockdown novel done, and it’s a very science fiction thing, so Tachyon is going to publish it next year. It’s called Neom, which is the name of a real proposed futuristic city in Saudi Arabia. I really love the idea of doing an annual short science fiction novel set in that world. That extended universe has so much going on, and I like the idea of doing one short novel a year of just pure science fiction, with robots and spaceships. I realized that I never really said what happens outside the Tel Aviv area in the Central Station-world version of Israel, so I started thinking, and now I’m working on what happens in the other bits. Neo-Neanderthal Cyberpunk, I think. That’s got to be a genre, right?

Interview design by Francesca Myman.

Read the full interview in the September 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.