The Year in Review 2020 by Ian Mond

Several things kept me sane over the last 12 months. My family, the privilege of having a job while in lockdown, the Backlisted and Coode Street podcasts (particularly Coode Street‘s “10 minutes with” series), and the books I read. Yes, there were times in 2020 where I struggled to read more than a handful of pages, but the novels, novellas, and collections I did complete (47 of which I reviewed for Locus) were some of the best books I’ve read in the last decade.

My favourite work of 2020, the book I know I will return to again and again until the pages are dog-eared and the spine has cracked, is Robert Shearman’s three-volume, 1,700-page, magnum opus We All Hear Stories in the Dark. The collection is framed around a man who is promised the return of his dead wife if he reads 101 stories in the correct order. Ingeniously, at the end of each piece, the reader is presented with five new stories to choose from. We’re told in the Prologue “these stories are for you… only for you” – but it’s not until you start your own journey through We All Hear Stories in the Dark that you realise what an extraordinary achievement this collection is: a reading experience that is both intensely personal but also has profound things to say about the nature of story-telling.

Adam Levin’s Bubblegum is a terrific novel that deserved more attention from the mainstream and genre press. Set in an alternate history where the internet is never invented, the populace is entertained by “Cures,” a manufactured pet born from a marble that smells like bubblegum but is so intensely adorable – especially when tortured – that people are prone to bite their heads off. The story is narrated by Belt Magnet, an unemployed writer who owns one of the oldest Cures in existence, making it a rare commodity. I’m usually not a big fan of socially awkward, middle-aged men crippled with self-doubt, but Belt is a magnificent creation, the one sympathetic person in a world where cruelty toward the harmless and innocent is a social norm.

On the other end of the spectrum, in terms of length and scope but certainly not quality, is Daisy Johnson’s Sisters. The novel centres on a mother and her two teenage daughters – July and September – who flee Oxford for the North York Moors where they take up residence in a ramshackle old house. Influenced by Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Johnson’s portrayal of the two sisters provides us with a twisted and darker version of Constance and Merricat. What stands out though, beyond the clever parallels with Jackson’s classic novel, is Johnson’s gorgeous, impressionistic prose, which imbues Sisters with an oppressive, claustrophobic atmosphere.

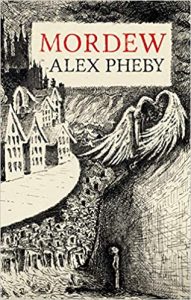

Whereas Daisy Johnson took her inspiration from Shirley Jackson, Alex Pheby’s epic fantasy novel Mordew (the first in a planned trilogy) takes its cues from Dickens and Mervyn Peake. Our young hero, Nathan Treeves, lives an impoverished life in the metropolis of Mordew, unaware of his family’s aristocratic pedigree. He also has an itch, a magical power, raw and uncontrolled, that brings him to the attention of the city’s Master. Yes, Mordew is a Chosen One narrative, but it’s one that packs in a trilogy’s worth of plot while presenting us with a working-class hero who, unlike so many Chosen Ones, never enjoys a moment of agency. A hilariously snarky, novella-length Glossary tops off the provocative and playful tone of Mordew. I typically keep away from epic fantasy series, but that won’t be the case here.

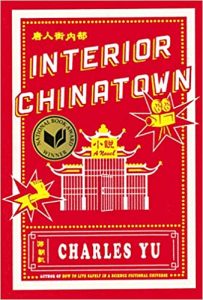

Stephen Graham Jones’ The Only Good Indians and Charles Yu’s Interior Chinatown are two books I didn’t review for Locus but wish I had (it’s OK though; they both got plenty of positive coverage from the critics). The Only Goods Indians (which I did discuss at length with Kirstyn McDermott on The Writer and the Critic podcast) tells the story of a group of Native American men who are haunted and literally stalked by the sins of their past. It’s a personal and brutal story about tradition, cultural identity, and assimilation that also happens to be that very rare thing: a genuinely terrifying horror novel. And then there’s the sublime Interior Chinatown, the deserving winner of 2020’s National Book Award. It’s a story about immigration presented as a screenplay of an episode of a very popular (and very fictional) police procedural Black and White. It should be pretentious bollocks, but the narrative arc of Yu’s main character Willis Wu, who has a bit role in the episode – Generic Asian Man – but dreams of one day becoming Kung Fu Guy, is not only incredibly funny and surreal but also highlights the struggles of being an immigrant in America and the tensions between different minority groups. There are observations and insights made in this novel about race in America that are as discerning as any 500-page study on the subject.

While I’ve picked out these five novels to discuss, frankly I could have switched them with at least ten other novels. Or, to put it another way, don’t pay attention to the short shrift I give the following books. For example, James Bradley’s Ghost Species is a terrific, thoughtful, and foreboding novel about the Anthropocene and the resurrection of the neanderthal species that makes it clear there’s no quick fix to climate change. Environmental collapse is also central to Lydia Millet’s A Children’s Bible, which elegantly weaves the Old and New Testament (including a flood Noah would be proud of) into a story about the generational shift in society’s response to climate change. There’s also a mythological flavour to Megan Hunter’s Harpy that draws on our shared fables – such as the harpy of antiquity – to tell a twisted, tragic, yet oftentimes funny story about infidelity and motherhood. Talking about mythology and motherhood, Maria Dahvana Headley’s remarkable new translation of Beowulf provides a contemporary and feminist flavour to this millennia-old epic-poem, including her genius translation of the Old English word “Hwaet” as “Bro.” Switching from ancient Danes to ancient Britons, Lavie Tidhar gives us his take on King Arthur with the rambunctious By Force Alone, a brilliant, revisionist blend of magic, crime syndicates, and Kung-fu knights.

While I’ve picked out these five novels to discuss, frankly I could have switched them with at least ten other novels. Or, to put it another way, don’t pay attention to the short shrift I give the following books. For example, James Bradley’s Ghost Species is a terrific, thoughtful, and foreboding novel about the Anthropocene and the resurrection of the neanderthal species that makes it clear there’s no quick fix to climate change. Environmental collapse is also central to Lydia Millet’s A Children’s Bible, which elegantly weaves the Old and New Testament (including a flood Noah would be proud of) into a story about the generational shift in society’s response to climate change. There’s also a mythological flavour to Megan Hunter’s Harpy that draws on our shared fables – such as the harpy of antiquity – to tell a twisted, tragic, yet oftentimes funny story about infidelity and motherhood. Talking about mythology and motherhood, Maria Dahvana Headley’s remarkable new translation of Beowulf provides a contemporary and feminist flavour to this millennia-old epic-poem, including her genius translation of the Old English word “Hwaet” as “Bro.” Switching from ancient Danes to ancient Britons, Lavie Tidhar gives us his take on King Arthur with the rambunctious By Force Alone, a brilliant, revisionist blend of magic, crime syndicates, and Kung-fu knights.

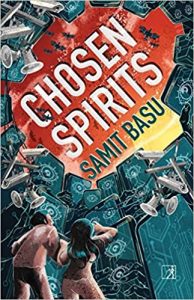

But there are so many other novels I loved, like Sophie Ward’s Love and Other Thought Experiments, a story of Artificial Intelligence and alternate realities that was longlisted for the Booker prize (who says the Booker judges don’t recognise genre fiction?); and M. John Harrison’s The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again, winner of 2020 Goldsmith Prize, that plays with the conventions of literary and genre fiction to transform a post-Brexit Britain into a world of uncertainty and wild conspiracy theories; and Hilary Leichter’s debut novel, Temporary, an absurdist and laugh-out-loud funny response to the real-world shift to casual employment and the gig-economy; and Chosen Spirits by Samit Basu, which portrays a near-future India that despite having all the hallmarks of a dystopia – the suppression of free speech, the manipulation of the media, the chasm between the rich and poor – is, according to its author, a “best-case scenario,” given the country’s current trajectory.

This year I also reviewed ten works in translation, including great novels by Samantha Schweblin (Little Eyes), Yoss (Red Dust), Hiroko Oyamada (The Hole), and Christiane Vadnais (Fauna). I was awed by the cruel, toxic, brutal dystopia of Guillermo Saccomano’s The Clerk; fascinated by the visionary and existential insights of the last man on Earth in Guido Morselli’s Dissipatio H.G.: The Vanishing; and horrified at how quickly humanity turns to cannibalism in Agustina Bazterrica’s darkly satirical Tender Is The Flesh. The translated work that left an indelible impression, that I still think about months after finishing it, was Earthlings by Sayaka Murata (translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori). Murata introduces us to Natsuki, who, at the age of 11, believes she has magical powers granted to her by a plush hedgehog from the Planet Popinpobopia, and then as an adult identifies herself as Popinpobopian, separate from the human race. But as Natsuki, along with her husband and childhood friend Yuu, deny their humanity and embrace their alienness, they walk a dark path, one that is shocking and harrowing but, more importantly, speaks to society’s inability (or unwillingness) to accept those who are different.

This year I also reviewed ten works in translation, including great novels by Samantha Schweblin (Little Eyes), Yoss (Red Dust), Hiroko Oyamada (The Hole), and Christiane Vadnais (Fauna). I was awed by the cruel, toxic, brutal dystopia of Guillermo Saccomano’s The Clerk; fascinated by the visionary and existential insights of the last man on Earth in Guido Morselli’s Dissipatio H.G.: The Vanishing; and horrified at how quickly humanity turns to cannibalism in Agustina Bazterrica’s darkly satirical Tender Is The Flesh. The translated work that left an indelible impression, that I still think about months after finishing it, was Earthlings by Sayaka Murata (translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori). Murata introduces us to Natsuki, who, at the age of 11, believes she has magical powers granted to her by a plush hedgehog from the Planet Popinpobopia, and then as an adult identifies herself as Popinpobopian, separate from the human race. But as Natsuki, along with her husband and childhood friend Yuu, deny their humanity and embrace their alienness, they walk a dark path, one that is shocking and harrowing but, more importantly, speaks to society’s inability (or unwillingness) to accept those who are different.

In a year that was genuinely awful for nearly everyone on the planet, I want to leave you with a novel that brought a large smile to my face. It’s not genre, which is why I’m sneaking it in at the end here, but it has a sensibility that genre fans will appreciate. The book is Eley Williams’s debut The Liar’s Dictionary, a story about the century-old production of an incomplete multi-volume Encyclopaedic Dictionary. Switching between the modern-day and the turn of the 20th century, and told from the perspective of two lexicographer’s working on the Dictionary, this novel, full of false words and mountweazels, is one of the funniest things I’ve read in years (there’s a scene involving a pelican that is comedy gold). So, if you’re looking for a book that will provide a little bit of respite from the anxiety of COVID, of a post-Trump world where Trump is still somehow a thing, and of the looming threat of climate change, then The Liar’s Dictionary, with its love for words both real and imaginary, is the book for you.

This review and more like it in the February 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.