The Colour of 2020 by Alvaro Zinos-Amaro

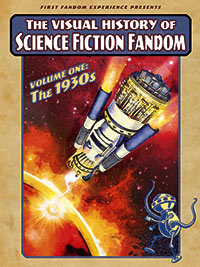

Our very strange year invited, among other things, mournful reflections on a past that felt abruptly truncated, and a number of non-fiction titles, though surely in production before the world’s temporary suspension, were eerily attuned to this backward gaze. Then again, SF/F/H have a tendency to steep themselves deeply in their own genre pasts and traditions, even as they often compost these into unexpected futures, so the apparent synchronicity may be illusory. At any rate, Jonathan R. Eller’s Bradbury Beyond Apollo satisfyingly closed out a minutely researched and finely realized three-volume biography of Ray Bradbury. This concluding tome covers his life and work from the late 1960s through the end of his life in 2012. Collection Beyond the Outposts: Essays on SF and Fantasy 1955-1996 encompasses a similar period, though in this case gathering texts by Algis Budrys. These two volumes, an academic biography of one very celebrated writer and a non-fiction collection by an important but lesser-known writer and editor, are complementary in interesting ways. Looking back farther still, David Ritter’s impressive The Visual History of Science Fiction Fandom, Volume One: The 1930’s has already established itself as an indispensable resource for scholars and a bounty of entertainment for history-curious readers. (Despite the price tag, I recommend the physical edition over the ebook.) For those interested in another pricey visual extravaganza, albeit a franchise-specific one, that manages to pack in plenty of text, Paul Duncan’s The Star Wars Archives: 1999–2005 will prove diverting. I had the pleasure of discussing Jess Nevins’s instructive Horror Fiction in the 20th Century: Exploring Literature’s Most Chilling Genre and the ambitious anthology edited by Dan Byrne-Smith, Science Fiction: Documents of Contemporary Art, in these pages last year, so I will use my remaining space to bring to your attention two worthwhile books I didn’t get around to covering. Both of these continue the theme of retrospective evaluation, but do so in ways that also excitingly signal to the future.

The first is non-fiction anthology Literary Afrofuturism in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Isiah Lavender III & Lisa Yaszek, which contains writing by the editors; an introductory roundtable discussion by Bill Campbell, N.K. Jemisin, Nisi Shawl, Minister Faust, Nalo Hopkinson, Chinelo Onwualu, and Nick Wood; followed by essays by Sheree R. Thomas, De Witt Douglas Kilgore, Gina Wisker, Rebecca Holden, Mark Bould, Elizabeth A. Wheeler, Lisa Dowdall, Gerry Canavan, Jerome Winter, Marleen S. Barr, and Nedine Moonsamy, along with outstanding illustrations by artist Stacey Robinson. The 12 chapter essays are organized in four sections that explore Afrofuturism as it is presently perceived by working artists, Afrofuturism’s relation to literary and cultural history respectively, and its relationship with Africa. The book’s essential purpose, state Lavender III & Yaszek in their excellent lead-in, is to “introduce readers to Afrofuturism as an aesthetic practice that enables artists to communicate the experience of science, technology, and race across centuries, continents, and cultures.” Emphasizing the special role of texts over other artistic expressions, they point out that “the printed word remains an important lens through which to understand the full dimensions of Afrofuturism.” They explore the origins of the term and various ways in which it has been interpreted, adapted, co-opted, repurposed, and renounced. This discussion introduces other fascinating concepts like “steamfunk,” “sword and soul fantasy,” “Astro-Blackness,” and the 2.0 and 3.0 incarnations of Afrofuturism itself. The lively roundtable that follows this introduction, which begins with an animated range of responses to the term itself, is alone worth the price of admission. Hopkinson points out that Afrofuturism “comes out of an African American experience. It doesn’t completely contain or reflect those of us whose root context isn’t American;” Jemisin doesn’t “really think of the term at all;” for Shawl it’s “a convenience for critics first, a marketing tool second, and third… a moment of attention in the stream of pop culture-consciousness;” Faust states several reasons for not accepting the term, among them that “much of Africentric fantasy is set in the past or the present, not the future, which makes the term ‘Afrofuturism‘ a failure from the start;” Wood comments that “the label looks like an attempt to hang a conceptual umbrella over a range of cultural products (e.g., music, art, and writing) from across the African diaspora in North America;” Campbell confesses that he’s not sure what the word “means or is supposed to mean.” When asked to speculate about the end of Afrofuturism, and what might succeed it, Jemisin hopes for “a broadening of literature so that it will no longer segregate ‘Africa’ and ‘the future’ from one another, and no longer lump Janet the steampunkista in with Jamel the literary zombie writer, just because the two share a color or an interest in protagonists who aren’t white.” Labels aside, the importance of Black speculative fiction, and the expansion of how literary speculative fiction is perceived to include, among other things, “Afrodiasporic and African history and culture,” emerge as unifying themes. Despite the reservations, implicit and explicit, at the term Afrofuturism, the next chapters, focusing on Black women writers, Afrofuturism as alternate history, Nalo Hopkinson’s The New Moon’s Arms, and young-adult Afrofuturism, make compelling cases for how Afrofuturism adds value to present-day science fiction. Additional pieces, on John M. Faucette, Afroaquanauts, and Jemisin’s acclaimed Broken Earth trilogy, tap into Afrofuturism as a means of better understanding black history. In the fourth and concluding section, discussions of Wakanda, global Afrofuturist ecologies, Deji Bryce Olukotun’s Nigerians in Space and Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard expand the conversation to Africa. Each chapter contains a section of works cited that easily doubles as suggestions for further reading, a treasure trove of recommendations. Harking back to a prefatory comment, this savvily edited and cogently organized volume offers frequent evidentiary reminders that Afrofuturism is “one possible mode of storytelling in a much larger tradition of black speculative fiction.” In a coda titled “Wokeness and Afrofuturism”, Lavender III & Yaszek re-engage the term and wrap up with a summation of sorts. They express regret at not having enough space to expound on what may lie beyond Afrofuturism, and ask whether the movement is a “colored wave” within SF/F/H, “analogous to an aesthetic movement such as the New Wave or cyberpunk,” or a multigenre phenomenon that will transcend and transform our fields, welcoming in a “colored age.”

The first is non-fiction anthology Literary Afrofuturism in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Isiah Lavender III & Lisa Yaszek, which contains writing by the editors; an introductory roundtable discussion by Bill Campbell, N.K. Jemisin, Nisi Shawl, Minister Faust, Nalo Hopkinson, Chinelo Onwualu, and Nick Wood; followed by essays by Sheree R. Thomas, De Witt Douglas Kilgore, Gina Wisker, Rebecca Holden, Mark Bould, Elizabeth A. Wheeler, Lisa Dowdall, Gerry Canavan, Jerome Winter, Marleen S. Barr, and Nedine Moonsamy, along with outstanding illustrations by artist Stacey Robinson. The 12 chapter essays are organized in four sections that explore Afrofuturism as it is presently perceived by working artists, Afrofuturism’s relation to literary and cultural history respectively, and its relationship with Africa. The book’s essential purpose, state Lavender III & Yaszek in their excellent lead-in, is to “introduce readers to Afrofuturism as an aesthetic practice that enables artists to communicate the experience of science, technology, and race across centuries, continents, and cultures.” Emphasizing the special role of texts over other artistic expressions, they point out that “the printed word remains an important lens through which to understand the full dimensions of Afrofuturism.” They explore the origins of the term and various ways in which it has been interpreted, adapted, co-opted, repurposed, and renounced. This discussion introduces other fascinating concepts like “steamfunk,” “sword and soul fantasy,” “Astro-Blackness,” and the 2.0 and 3.0 incarnations of Afrofuturism itself. The lively roundtable that follows this introduction, which begins with an animated range of responses to the term itself, is alone worth the price of admission. Hopkinson points out that Afrofuturism “comes out of an African American experience. It doesn’t completely contain or reflect those of us whose root context isn’t American;” Jemisin doesn’t “really think of the term at all;” for Shawl it’s “a convenience for critics first, a marketing tool second, and third… a moment of attention in the stream of pop culture-consciousness;” Faust states several reasons for not accepting the term, among them that “much of Africentric fantasy is set in the past or the present, not the future, which makes the term ‘Afrofuturism‘ a failure from the start;” Wood comments that “the label looks like an attempt to hang a conceptual umbrella over a range of cultural products (e.g., music, art, and writing) from across the African diaspora in North America;” Campbell confesses that he’s not sure what the word “means or is supposed to mean.” When asked to speculate about the end of Afrofuturism, and what might succeed it, Jemisin hopes for “a broadening of literature so that it will no longer segregate ‘Africa’ and ‘the future’ from one another, and no longer lump Janet the steampunkista in with Jamel the literary zombie writer, just because the two share a color or an interest in protagonists who aren’t white.” Labels aside, the importance of Black speculative fiction, and the expansion of how literary speculative fiction is perceived to include, among other things, “Afrodiasporic and African history and culture,” emerge as unifying themes. Despite the reservations, implicit and explicit, at the term Afrofuturism, the next chapters, focusing on Black women writers, Afrofuturism as alternate history, Nalo Hopkinson’s The New Moon’s Arms, and young-adult Afrofuturism, make compelling cases for how Afrofuturism adds value to present-day science fiction. Additional pieces, on John M. Faucette, Afroaquanauts, and Jemisin’s acclaimed Broken Earth trilogy, tap into Afrofuturism as a means of better understanding black history. In the fourth and concluding section, discussions of Wakanda, global Afrofuturist ecologies, Deji Bryce Olukotun’s Nigerians in Space and Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard expand the conversation to Africa. Each chapter contains a section of works cited that easily doubles as suggestions for further reading, a treasure trove of recommendations. Harking back to a prefatory comment, this savvily edited and cogently organized volume offers frequent evidentiary reminders that Afrofuturism is “one possible mode of storytelling in a much larger tradition of black speculative fiction.” In a coda titled “Wokeness and Afrofuturism”, Lavender III & Yaszek re-engage the term and wrap up with a summation of sorts. They express regret at not having enough space to expound on what may lie beyond Afrofuturism, and ask whether the movement is a “colored wave” within SF/F/H, “analogous to an aesthetic movement such as the New Wave or cyberpunk,” or a multigenre phenomenon that will transcend and transform our fields, welcoming in a “colored age.”

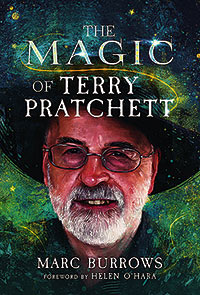

Next up is Marc Burrows’s affable and consistently engaging The Magic of Terry Pratchett, the first full-fledged biography of the massively popular British fantasist. Burrows regrets never having met Pratchett, and enticingly positions this book as an invitation to join him in a literary encounter with the author, via a wealth of primary and secondary interviews, convention speeches, and other records. The always-enthusiastic Burrows concedes the preliminary nature of this biography, first to the punch but likely to be superseded, at least in scale, by Rob Wilkins’s, which will stem from a close working partnership with Pratchett. For those, like me, who only knew Pratchett’s media persona, surprises about his temperament arrive quickly: he was “often furious,” he had a “simmering sense of outrage,” and he “didn’t suffer fools.” The volume’s early chapters cover Pratchett’s poor but contented and imaginatively fecund childhood, his voracious reading, his early notable influences (Richmal Crompton’s Just William books, Tove Jansson’s Moomins series, P.G. Wodehouse, Jules Verne, Arthur Conan Doyle, and particularly G.K. Chesterton, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Punch magazine), his formative years at Bucks Free Press and other journalistic outfits, through to his first pro short story sale at a precocious 14. Pratchett’s gift for subversion of fantasy tropes becomes evident in his earliest forays into fiction, and though Tolkien initially looms large, the eclipse has mostly passed by the time Pratchett publishes his second novel. We follow along as Pratchett gets married, finds publishing success while working as a Press Officer for the Central Electricity Generating Board, transitions to full-time writing, attains cult status, and eventual mega-bestseller-dom. Burrows is a keen reader of Pratchett’s fiction, and a number of later chapters, chronicling years of ceaseless productivity (between ’88 and ’92, for instance, Pratchett published seventeen novels) fall into a familiar cadence: a description of how each work was conceived, its main plot and themes, its location in the canon based on its relative merits, and its reception by the critics and public alike. Pratchett’s involvement with fandom, via the convention circuit as well as online message boards, is further scanned for insights into his personality and values. The final poignant sections depict Pratchett’s public battle with a rare form of Alzheimer’s, his activism around raising Alzheimer’s awareness, and his impassioned exploration of assisted suicide. Burrow’s literary analysis expounds on Pratchett’s trademark techniques, given curious names like “sherbet lemons,” “cigarettes,” and “figgins.” Burrow’s buoyant, pun-peppered, and aptly footnote-flecked style, though occasionally repetitive, helpfully marries his subject matter, propelling us through decade after decade of a heavily writing-centric life while illuminating Pratchett’s complexities and contradictions without any drag in the tempo. Pratchett’s self-awareness always shines through. As Burrows points out, “Pratchett knew that the Discworld was the foundation of his fortune, but he had refused to let it be an albatross around his neck,” a move that considerably enhanced Pratchett’s body of work and extended its longevity. Regarding the man’s own self-mythologizing, Burrows astutely points out that many Pratchett anecdotes are different based on the source, so it’s up to us to choose which version to believe. A succinct, eloquent description of the morality that emerges from Pratchett’s oeuvre – “think for yourself but work together, be imaginative but don’t rely on shortcuts, be sensible and clever and use bravery as a back-up plan, and above all things be decent” – makes it clear that despite any narrative embroidering of the truth, Pratchett lived his life in beautiful harmony with his beliefs. What better inspiration as we move through the new year?

Next up is Marc Burrows’s affable and consistently engaging The Magic of Terry Pratchett, the first full-fledged biography of the massively popular British fantasist. Burrows regrets never having met Pratchett, and enticingly positions this book as an invitation to join him in a literary encounter with the author, via a wealth of primary and secondary interviews, convention speeches, and other records. The always-enthusiastic Burrows concedes the preliminary nature of this biography, first to the punch but likely to be superseded, at least in scale, by Rob Wilkins’s, which will stem from a close working partnership with Pratchett. For those, like me, who only knew Pratchett’s media persona, surprises about his temperament arrive quickly: he was “often furious,” he had a “simmering sense of outrage,” and he “didn’t suffer fools.” The volume’s early chapters cover Pratchett’s poor but contented and imaginatively fecund childhood, his voracious reading, his early notable influences (Richmal Crompton’s Just William books, Tove Jansson’s Moomins series, P.G. Wodehouse, Jules Verne, Arthur Conan Doyle, and particularly G.K. Chesterton, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Punch magazine), his formative years at Bucks Free Press and other journalistic outfits, through to his first pro short story sale at a precocious 14. Pratchett’s gift for subversion of fantasy tropes becomes evident in his earliest forays into fiction, and though Tolkien initially looms large, the eclipse has mostly passed by the time Pratchett publishes his second novel. We follow along as Pratchett gets married, finds publishing success while working as a Press Officer for the Central Electricity Generating Board, transitions to full-time writing, attains cult status, and eventual mega-bestseller-dom. Burrows is a keen reader of Pratchett’s fiction, and a number of later chapters, chronicling years of ceaseless productivity (between ’88 and ’92, for instance, Pratchett published seventeen novels) fall into a familiar cadence: a description of how each work was conceived, its main plot and themes, its location in the canon based on its relative merits, and its reception by the critics and public alike. Pratchett’s involvement with fandom, via the convention circuit as well as online message boards, is further scanned for insights into his personality and values. The final poignant sections depict Pratchett’s public battle with a rare form of Alzheimer’s, his activism around raising Alzheimer’s awareness, and his impassioned exploration of assisted suicide. Burrow’s literary analysis expounds on Pratchett’s trademark techniques, given curious names like “sherbet lemons,” “cigarettes,” and “figgins.” Burrow’s buoyant, pun-peppered, and aptly footnote-flecked style, though occasionally repetitive, helpfully marries his subject matter, propelling us through decade after decade of a heavily writing-centric life while illuminating Pratchett’s complexities and contradictions without any drag in the tempo. Pratchett’s self-awareness always shines through. As Burrows points out, “Pratchett knew that the Discworld was the foundation of his fortune, but he had refused to let it be an albatross around his neck,” a move that considerably enhanced Pratchett’s body of work and extended its longevity. Regarding the man’s own self-mythologizing, Burrows astutely points out that many Pratchett anecdotes are different based on the source, so it’s up to us to choose which version to believe. A succinct, eloquent description of the morality that emerges from Pratchett’s oeuvre – “think for yourself but work together, be imaginative but don’t rely on shortcuts, be sensible and clever and use bravery as a back-up plan, and above all things be decent” – makes it clear that despite any narrative embroidering of the truth, Pratchett lived his life in beautiful harmony with his beliefs. What better inspiration as we move through the new year?

This review and more like it in the February 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.