SF in a Plague Year by Rich Horton

As I write, distribution of two separate COVID-19 vaccines is in progress in the United States. A new President has been elected and will soon be inaugurated. And on a personal note, I have welcomed my first grandchild into the world. A time of optimism, right?

At the same time, COVID cases are at or near their highest rate of incidence in the US (and indeed, in many countries). The vaccine distribution is a hopeful sign but is going more slowly than we might wish. Though the new President was elected by a considerable margin, the outgoing President continues to dispute the election, going so far as to threaten a member of his own party, the Secretary of State of Georgia, with criminal charges if he can’t “find” enough votes to alter the result of the election in that state. On a personal note, the list of over 300,000 deaths from COVID in the US includes my aunt and a close personal friend at work. Surely this parallels numerous SFnal examples of dystopias, doesn’t it?

SF is a literature of hope, of optimism, of discovery, of change, of utopia. At the same time it can be a literature of despair, of dystopia, of environmental destruction, of our urge to discover leading to harm, of change meaning loss. I guess all of the above means SF is a literature for our time – for any time. (To be fair, all fiction is similarly bipolar – but SF I think more obviously so, more directly so.)

It has often been said often that much SF is “really” set in the present, or the near past. That is, the futures or alternate worlds depicted are often metaphorical reflections of the writer’s immediate contemporary concerns, or the ways in the which the setting is “stranged” are really a reaction to present-day problems or to present-day hopes. What does this mean for the best stories I saw in 2020? Partly it means that, well, as they were written pre-pandemic, and while not pre-Trump, prior to his messy exit, they don’t necessarily directly reflect what we’ve all just lived through. But there’s a thing about the very best stories (in any field) – if they are really great, they are timeless to some extent, and so they will (if obliquely) comment on our human condition no matter the specific issue they address. And, too, SF should be able to (we think!) anticipate at least generally the dreams and nightmares we face. So – here is a look at some of my favorite 2020 stories.

It has often been said often that much SF is “really” set in the present, or the near past. That is, the futures or alternate worlds depicted are often metaphorical reflections of the writer’s immediate contemporary concerns, or the ways in the which the setting is “stranged” are really a reaction to present-day problems or to present-day hopes. What does this mean for the best stories I saw in 2020? Partly it means that, well, as they were written pre-pandemic, and while not pre-Trump, prior to his messy exit, they don’t necessarily directly reflect what we’ve all just lived through. But there’s a thing about the very best stories (in any field) – if they are really great, they are timeless to some extent, and so they will (if obliquely) comment on our human condition no matter the specific issue they address. And, too, SF should be able to (we think!) anticipate at least generally the dreams and nightmares we face. So – here is a look at some of my favorite 2020 stories.

One way to look at how SF addresses contemporary concerns is to look at the stories from outside the genre. The best SF story this year from the New Yorker was “Out There” by Kate Folk, about biomorphic humanoids originally developed as caretakers, but now appropriated for use in fraudulent activity, especially identity theft, and as such often seen on dating apps. In 2020 terms, the idea of dating a non-human might seem to have unexpected benefits (they’re presumably not infectious!) but the story is of course more focused on the ever-relevant issues of human relationships. Alexander Weinstein put out a new story collection, Universal Love, with a lot of fine stories, but it is “Beijing” that seems most apposite: about David, a gay man whose relationship with his lover seems to be fraying – and his lover urges him to “patch” the troubling parts of his memory, including his family, who won’t accept his sexuality. But David doesn’t want to lose even painful memories – especially as he realizes his lover is patching some of their past…. Add all that – how many of us have painful memories this year! – to the images of a pollution-racked Beijing.

It turns out this was C.C. Finlay’s last full year with F&SF, as we have just learned that he has resigned, to be replaced by Sheree Renée Thomas. Among the great stories he published was Amanda Hollander’s “A Feast of Butterflies”, about a constable serving a remote town that is de facto ruled by a corrupt local landowner, who has allowed his son and his son’s friends to run rampant without punishment. When the young men go missing, the landowner demands the constable arrest a young woman in a remote village – a woman whose brother had been killed by the landowner’s son’s gang. The constable finds that the woman has become strange indeed, and the fate of the evil young men is quite fascinating, leading to a delicious, subtle conclusion. Also “Stepsister” by Leah Cypess, a truly clever Cinderella reimagination from the POV of one of the stepsisters, which has a wonderful plot but is also a story of character wonderfully resolved as well – the beautiful plot wouldn’t work if we didn’t believe in the motivations – in the love! – of each of the characters.

It turns out this was C.C. Finlay’s last full year with F&SF, as we have just learned that he has resigned, to be replaced by Sheree Renée Thomas. Among the great stories he published was Amanda Hollander’s “A Feast of Butterflies”, about a constable serving a remote town that is de facto ruled by a corrupt local landowner, who has allowed his son and his son’s friends to run rampant without punishment. When the young men go missing, the landowner demands the constable arrest a young woman in a remote village – a woman whose brother had been killed by the landowner’s son’s gang. The constable finds that the woman has become strange indeed, and the fate of the evil young men is quite fascinating, leading to a delicious, subtle conclusion. Also “Stepsister” by Leah Cypess, a truly clever Cinderella reimagination from the POV of one of the stepsisters, which has a wonderful plot but is also a story of character wonderfully resolved as well – the beautiful plot wouldn’t work if we didn’t believe in the motivations – in the love! – of each of the characters.

Nadia Afifi‘s “The Bahrain Underground Bazaar” is another excellent F&SF piece, about Zahra, who, as her health declines, has been visiting the bazaar to experience recordings of people dying – leading to a trip to Petra to try to understand one Bedouin woman’s motivations – and inevitably thus learning more about her herself.

In Asimov’s one story that especially stuck out was Mercurio D. Rivera‘s “Beyond the Tattered Veil of Stars” in the lineage of Theodore Sturgeon’s “Microcosmic God”. It’s told in two threads – one follows a series of entries from the chronicles of an alien race as they deal with a series of catastrophes. The other is told by a journalist involved with an old friend of his, who has created something remarkable: a virtual simulation of an alternate world, in which she subjects her simulated creatures to horrible crises, in the hope that their ingenuity will create something she can use in our Earth to deal with our problems. The story deals effectively with the ethical issues this raises – and the ethical issues surrounding the journalist’s motives – and also with the reactions of the simulated creatures, leading to a striking and dark (if ambiguously hopeful, but for who?) conclusion.

In Asimov’s one story that especially stuck out was Mercurio D. Rivera‘s “Beyond the Tattered Veil of Stars” in the lineage of Theodore Sturgeon’s “Microcosmic God”. It’s told in two threads – one follows a series of entries from the chronicles of an alien race as they deal with a series of catastrophes. The other is told by a journalist involved with an old friend of his, who has created something remarkable: a virtual simulation of an alternate world, in which she subjects her simulated creatures to horrible crises, in the hope that their ingenuity will create something she can use in our Earth to deal with our problems. The story deals effectively with the ethical issues this raises – and the ethical issues surrounding the journalist’s motives – and also with the reactions of the simulated creatures, leading to a striking and dark (if ambiguously hopeful, but for who?) conclusion.

Also excellent in Asimov’s was “Bereft, I Come to a Nameless World” by Benjamin Rosenbaum. This is set in the very far future, when humans (or, really, posthumans) have dispersed across the stars… altering worlds, altering themselves, but, it seems, doomed to catastrophe, wars, and violence. Siob, a constructed being, is fleeing yet another failed utopia, and returns to a world he’s known before, and another of his fellows… ah, best to read it: a meditation on humanity, destiny, time, fate – and a far future story, that like the best of such, is still really about us, now.

Less pertinent perhaps, but so good I need to mention it, was “When God Sits in Your Lap” by Ian Tregillis, told from the POV of a fallen angel, in a noirish Los Angeles (think Raymond Chandler). It’s Damon Runyonesque snappy noir, concerning human corruption and a war in heaven – and by the end much darker than its tone, powerful and moving.

Less pertinent perhaps, but so good I need to mention it, was “When God Sits in Your Lap” by Ian Tregillis, told from the POV of a fallen angel, in a noirish Los Angeles (think Raymond Chandler). It’s Damon Runyonesque snappy noir, concerning human corruption and a war in heaven – and by the end much darker than its tone, powerful and moving.

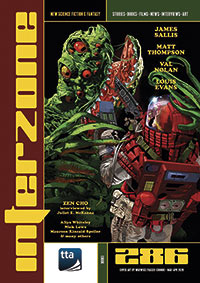

What most stood out from Interzone is a novelette by the great James Sallis, “Carriers“, which begins in a strange place and ends up somewhere completely different (though still plenty strange). At first it seems to be about a post-apocalyptic US, environmentally decaying and featuring a doctor trying to treat the disadavantaged. Topical enough! – and then we move decades in the future, to another odd encounter between the doctor and a man he had saved long ago, with a mysterious sort of ghost present as well. It’s simply differently powerful, in a way I’m coming to associate with Sallis.

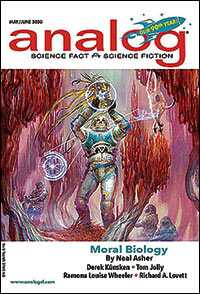

From Analog, one story really did seem topical, from one of our best newer writers, Dominica Phetteplace: “Candida Eve“, about a woman on a mission to Mars while Earth – and her own crew – is ravaged by a new plague. Susana is fortunate to be resistant to the plague, and the story shows her lonely first few weeks on Mars, setting up her robot assistants, communicating with Earth, and waiting for the next ship to come. It’s in the center of the Analog tradition, but quite original as well.

Another striking Interzone piece was Eugenia Triantafyllou‘s “Those We Serve“, which in 2020 terms can be seen (a bit trivially) as dealing with the crisis in the service industry, and also with radical inequality. Manoli is one of the summer staff on a tourist island, and we quickly understand that that means he’s an illegal copy, an android perhaps, of a human who lives underground all year, while the summer and winter staff maintain the island and serve the tourists. Manoli, however, always waits for the visits of Amelia, a tourist who has been coming since her teenage years. But things are changing, and Manoli’s future is in doubt. I believed in his humanity, and the story won me over.

Another striking Interzone piece was Eugenia Triantafyllou‘s “Those We Serve“, which in 2020 terms can be seen (a bit trivially) as dealing with the crisis in the service industry, and also with radical inequality. Manoli is one of the summer staff on a tourist island, and we quickly understand that that means he’s an illegal copy, an android perhaps, of a human who lives underground all year, while the summer and winter staff maintain the island and serve the tourists. Manoli, however, always waits for the visits of Amelia, a tourist who has been coming since her teenage years. But things are changing, and Manoli’s future is in doubt. I believed in his humanity, and the story won me over.

I won’t vouch for the direct topicality of “Laws of Impermanence” by Ken Schneyer, but it was my favorite Uncanny story from 2020. It’s built around a truly striking – and very fruitful – concept: according to the title laws, written texts degrade over time, at a predictable rate. It’s both clever, in adumbrating the implications of these Laws, and quite moving, in showing the impact of this on one woman’s fraught personal history.

Finally, from Past Tense, a companion to John Benson’s long-running ‘zine Not One of Us, I loved a story that represented more of an escape from reality – into art – and that was something I needed. This is Alexandra Seidel‘s “Lovers on a Bridge” about Gretchen, who finds herself, somehow, in an art museum, fascinated by a painting. Soon she is accompanied by a man, the Curator of this museum, and together they take a tour of some of the paintings. There is even a hint that these paintings (real ones) are different – perhaps they can be entered. And there is certainly something strange – but not sinister – about the Curator. This story has the frisson of potential horror always there – but that’s not where it’s going.

Rich Horton works for a major aerospace company in St. Louis MO. He has published over a dozen anthologies, including the yearly series The Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy from Prime Books, and he is the Reprint Editor for Lightspeed Magazine. He contributes articles and reviews on SF and SF history to numerous publications.

This review and more like it in the February 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.