2020 Year in Review by Graham Sleight

Publishing lead-times being what they are, the extraordinary events of 2020 largely weren’t reflected in the books that came out in the year – or at least, not intentionally. I managed to read a good deal of thought-provoking SF and fantasy this year, but some books seemed even more relevant than expected because of the pandemic-shuttered world they emerged into. How posterity will view them – let alone how it’ll view the books that’ll doubtless follow about COVID itself – is a question for another day.

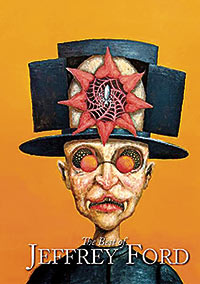

Samit Basu’s Chosen Spirits (Simon & Schuster India) offered a picture of India that was, its author insisted, both a dystopia and less bad than some alternatives. It certainly dug into the country’s culture and how it might change under the pressures bearing down on it. The Best of Elizabeth Bear (Subterranean) was a vast retrospective of this author’s short work: at her energetic best, as in many of the tales collected here, she convinces you she can bring newness to any genre. Piranesi (Bloomsbury) by Susanna Clarke was one of those books that ended up describing 2020, and as different as could be from its predecessor Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell (2004). Its protagonist is locked into a vast castle or world: the action of the book unpacks how he got there and, finally, whether he wants to belong there. His transparent goodness made these choices all the more poignant. Anne Charnock’s Bridge 108 (Amazon Publishing) humanely depicted a grim near-future Britain and Europe: a book it was hard to avert your eyes from. Cory Doctorow’s Attack Surface (Tor) was a return to the world of Little Brother (2008), this time digging into the co-option of technology by power (whether of the state or corporations) and what it might mean to be a part of that system. City Under the Stars by Gardner Dozois & Michael Swanwick (Tor) was, inevitably, a somewhat odd book – a completion by Swanwick after Dozois’s death, of an earlier collaborative novella. It had something of both the authors’ strengths: Swanwick’s inventive moral fervour and Dozois’s talent for story-engineering. Kate Elliott’s Unconquerable Sun (Tor) was an exuberant widescreen space opera, revelling in its riffs on history and politics: more volumes are awaited. The Best of Jeffrey Ford (PS) was another lengthy retrospective, from an author who always seems to find new ways to evoke the uncanny.

William Gibson’s Agency (Berkley) was evidently shaped by Donald Trump’s election as US President, and it’s no fault of the novel’s that it was overtaken by an entirely different set of global events. Gibson’s observational wit – that sense that he’s making you see your world anew – was as sharp as ever. Elizabeth Hand’s The Book of Lamps and Banners (Mulholland) was of associational interest, but for many of those (like me) who’ve been closely following her unusual detective Cass Neary, it was just the book we wanted. M. John Harrison is another author who’s unmistakable with every sentence they write: The Sunken Land Begins To Rise Again (Gollancz) returns him to an England unforgettably haunted by itself and the changes that wrack it. Harrison’s Settling the World: Selected Stories 1970-2020 (Comma Press) was a helpful retrospective, though many fine stories inevitably had to be omitted. Maria Dahvana Headley’s Beowulf: A New Translation (FSG) continued the bracing revisionist work begun in The Mere Wife a few years ago: the translation’s newness begins from the very first word. N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became (Orbit) was a thrilling fantasy of New York City, making its virtues and vices embodied. Its central argument, I think, was that cities are always pluralisms. Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Relentless Moon (Tor) continued her Lady Astronaut series’ examination of the costs and joys of near-future space travel.

William Gibson’s Agency (Berkley) was evidently shaped by Donald Trump’s election as US President, and it’s no fault of the novel’s that it was overtaken by an entirely different set of global events. Gibson’s observational wit – that sense that he’s making you see your world anew – was as sharp as ever. Elizabeth Hand’s The Book of Lamps and Banners (Mulholland) was of associational interest, but for many of those (like me) who’ve been closely following her unusual detective Cass Neary, it was just the book we wanted. M. John Harrison is another author who’s unmistakable with every sentence they write: The Sunken Land Begins To Rise Again (Gollancz) returns him to an England unforgettably haunted by itself and the changes that wrack it. Harrison’s Settling the World: Selected Stories 1970-2020 (Comma Press) was a helpful retrospective, though many fine stories inevitably had to be omitted. Maria Dahvana Headley’s Beowulf: A New Translation (FSG) continued the bracing revisionist work begun in The Mere Wife a few years ago: the translation’s newness begins from the very first word. N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became (Orbit) was a thrilling fantasy of New York City, making its virtues and vices embodied. Its central argument, I think, was that cities are always pluralisms. Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Relentless Moon (Tor) continued her Lady Astronaut series’ examination of the costs and joys of near-future space travel.

Paul McAuley’s War of the Maps (Gollancz) had a radical hard-SF setting, vast ocean voyages, and arguments about how society can and should be built. Sam J. Miller’s The Blade Between (Ecco) was a fine, disturbing ghost story about the bones of the past that lie under all our feet. Lydia Millet’s A Children’s Bible (Norton) was another book that seemed peculiarly well timed for 2020: what would it mean to be stuck in a remote house, watching something like an apocalypse descend? Tamsyn Muir’s Harrow the Ninth (Tor) followed up last year’s Gideon the Ninth with, if anything, even greater intensity. Certainly it felt like a much denser book, memes flying past faster than the eye could see – all packed into a story of goth space necromancers, whose concluding volume I eagerly await. Patrick Ness’s Burn (Walker) drops dragons into our world, with extensive and intricate consequences. As luck would have it, a few months before Ben Okri’s The Freedom Artist (Akashic) arrived, I’d read his Booker-winning The Famished Road (1991): both share a riveting sense that society is what people dream, for better or worse. The new book is open to the strangeness and terror engendered by that. Christopher Priest’s The Evidence (Gollancz) returned, again, to the author’s Dream Archipelago setting, this time marrying it with a crime story. Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future (Orbit) was everything you expect a Kim Stanley Robinson novel to be: thoughtful, grown-up, politically engaged, attempting to render historical change into the shape of a story.

Robert Shearman’s We All Hear Stories in the Dark (PS Publishing) was perhaps the most formidable work of the year: a huge labyrinth of strange stories that seemed to shift in meaning every time you turned a new corner. It was one to read slowly and in small doses. Michael Swanwick’s The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus (Subterranean) collected these exuberant tales that the author has been publishing for a couple of decades now. Swanwick’s enthusiastic pillaging of tropes from all genres was never clearer. Jo Walton’s Or What You Will (Tor) tackled, even more directly than the author’s previous works, the question of how stories get made and why: there may be no author more engaged than her with the idea that SF/F is built on its past. Jeff VanderMeer’s A Peculiar Peril (FSG) was a vivid, intricate alternate-world YA novel, packed with ideas, and to be followed by a sequel. Finally, Gene Wolfe’s Interlibrary Loan (Tor) was a sequel to the earlier A Borrowed Man (2015). I was fascinated by its intricacies while also doubting that it answered all the questions it raised. But with Wolfe, to the last, you never quite knew.

Robert Shearman’s We All Hear Stories in the Dark (PS Publishing) was perhaps the most formidable work of the year: a huge labyrinth of strange stories that seemed to shift in meaning every time you turned a new corner. It was one to read slowly and in small doses. Michael Swanwick’s The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus (Subterranean) collected these exuberant tales that the author has been publishing for a couple of decades now. Swanwick’s enthusiastic pillaging of tropes from all genres was never clearer. Jo Walton’s Or What You Will (Tor) tackled, even more directly than the author’s previous works, the question of how stories get made and why: there may be no author more engaged than her with the idea that SF/F is built on its past. Jeff VanderMeer’s A Peculiar Peril (FSG) was a vivid, intricate alternate-world YA novel, packed with ideas, and to be followed by a sequel. Finally, Gene Wolfe’s Interlibrary Loan (Tor) was a sequel to the earlier A Borrowed Man (2015). I was fascinated by its intricacies while also doubting that it answered all the questions it raised. But with Wolfe, to the last, you never quite knew.

Ten books of the year

The Best of Elizabeth Bear, Elizabeth Bear (Subterranean)

Piranesi, Susanna Clarke (Bloomsbury)

Agency, William Gibson (Berkley)

The Sunken Land Begins To Rise Again, M. John Harrison (Gollancz)

Beowulf: A New Translation, Maria Dahvana Headley (FSG)

The City We Became, N.K. Jemisin (Orbit)

Harrow the Ninth, Tamsyn Muir (Tordotcom)

The Ministry for the Future, Kim Stanley Robinson (Orbit)

We All Hear Stories in the Dark, Robert Shearman (PS Publishing)

Or What You Will, Jo Walton (Tor)

This review and more like it in the February 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.