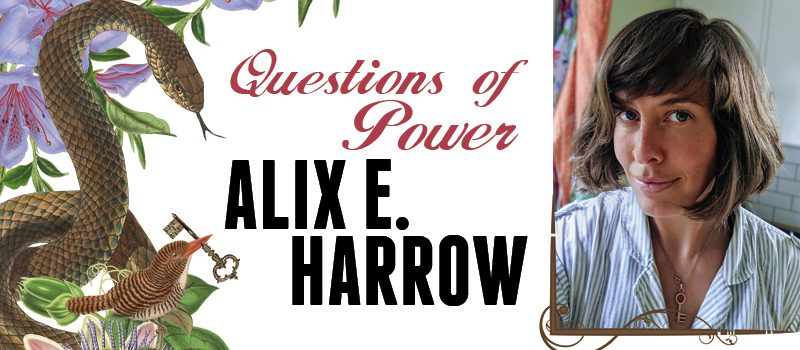

Alix E. Harrow: Questions of Power

Alix E. Harrow was born November 9, 1989 in Idaho and grew up in Colorado and Kentucky. She went to Berea College at age 16, graduating in 2009 with a degree in history. She worked various jobs, including as a research assistant, cashier, housekeeper, instructional designer, and migrant farmworker, before earning a master’s in history at the University of Vermont. She taught history at Eastern Kentucky University before becoming a full-time writer. Harrow lives in Kentucky with her husband and two children.

She began publishing with story “A Whisper in the Weld” in Shimmer (2014) and won a Hugo Award for short story “A Witch’s Guide to Escape: A Practical Compendium of Portal Fantasies” (2018), also a World Fantasy and Nebula Award finalist. “Do Not Look Back, My Lion” (2019) was a Hugo Award finalist, too.

Her debut novel, postcolonial portal fantasy The Ten Thousand Doors of January (2019), was a finalist for Hugo, World Fantasy, and Nebula Awards. Her latest book is alternate historical fantasy The Once and Future Witches (2020).

Excerpts from the interview:

“I absolutely grew up with the kind of bookish, idyllic childhood that you might imagine someone who grew up to write books about books would have. My mom was an English literature and history double major, and my house was already fully stocked with Victorian children’s literature. We had a huge amount of African-American lit too, because that was her focus in her major; we had her post-hippie-era political theory stuff, and she read me ‘Civil Disobedience’ at a very young and formative age. It’s unbelievably lucky that I had that, because I was also in rural Kentucky, and I don’t have any fond early childhood memories of our libraries. Now they’re a lot better and a lot better-funded, but back then it was like an old couple running a one-room library that smelled like cigarette smoke and only had Christian romances – it wasn’t a place that was going to expand my horizons. My school library wasn’t much better. One of my biggest early fights was with our school librarian because she wouldn’t let me check out The Hobbit, or, weirdly, Little Women – which I thought was what every eight-year-old girl was supposed to be reading – because she felt like they were above my level. Actual libraries were theoretical. My mom’s library that she gave me was perfect.

“I went to Berea College for undergrad, which is a liberal arts school for people from low-income backgrounds, and it gives you a full ride. I went there and I got my history degree, which I think is a degree you would only get if you weren’t taking out student loans for it. I’m very grateful for that. I graduated at the beginning of the recession, which is a great moment to graduate with a liberal arts degree – I totally recommend it. I did migrant farm work for a couple of years before I went back and got a master’s in history, because if it didn’t work the first time, why not do more history? Just keep digging – it’s fine. I absolutely regret none of that. In my master’s degree, I studied the British Empire, but in general I was interested in questions of power and how we got the power structures that we have today, looking at constructions of race, class, and gender in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. I ended up teaching as an adjunct professor at Eastern Kentucky University in the African and African-American Studies program. I was adjuncting, so I wasn’t making much money, but I was able to work within my degree, which is kind of rare.

“I wrote an absolutely atrocious, egregious novel in middle school. I would like to give a shout-out to Mrs. Parsons, my language arts teacher in seventh and eighth grades, for staying late and reading my book chapter by chapter, which is just above and beyond. Absolutely unnecessary. Twelve-year-olds are pretty brave, and they’re like, ‘I want to be a fantasy writer, so I’m going to write a fantasy book.’ I did, and it was fantastic. I mean, the book was terrible, but the experience was fantastic. After that I became very interested in being a serious adult and abandoning childish things, so I didn’t write any fiction from ages 13 to maybe 23 or 24. I was doing academic writing, which teaches you more about fiction writing than a lot of people give it credit for. I never took a creative writing class, but I did write a lot of history papers. When you do that, you’re assembling arguments from found objects and you’re trying to sell people a narrative, and that’s a similar skill. It wasn’t until after grad school, when I was adjuncting, that I started writing short stories and quietly working on The Ten Thousand Doors of January in the background.

“I’m really bad at elevator pitches, but I often say The Ten Thousand Doors of January is Narnia 2.0, or postcolonial Narnia. The premise is familiar – it follows a young girl at the turn of the 20th century who discovers a magic door to another world. Except there’s also a book within a book, and some footnotes which I still can’t believe my editor let me keep, and a very awful dog.

“The original conception for this book is something that I’ve only been able to see clearly in retrospect, because I just sat down and started writing it. The first three to five pages remained more or less unchanged throughout all the drafts. That’s the only part that remained unchanged. It’s been a process of realizing what pieces were rattling around in my brain to get me those first three pages. Those pieces were essentially that I was a kid who grew up on books, and particularly late Victorian-era children’s fiction: your Peter Pans, your Alices in Wonderlands, and, later on, your Narnias. I grew up with this very imaginative, wonderful world of little kids finding ways into other worlds. Then I went to grad school, and studied that fiction through the lens of imperialism and culture-building, and discovered that many of these s tories weren’t children’s fantasies as much as colonial fantasies that functioned in many ways to present a hideous vision of reality, and to train future citizens of the empire. From my broken-heartedness over those realizations came a desire to write a book that preserved the sense of wonder, but subverted, in at least some ways, those power dynamics.

“I rewrote the novel several times, but I’m a person who tends to rewrite before my first draft is done, which is terrible, and no one should do it. My books are constantly evolving things, as I write them. The heart of what I wanted the book to be mostly stayed the same throughout those rewrites – I wanted it to be about wonder and escapism and all of that, but also about storytelling itself, and how the stories we tell don’t just reveal our identities, but actively shape them That’s the cultural history training jumping out.

“I don’t know if it worked, in the end, but I know I learned a lot. For example, I didn’t know a lot about structure and pacing when I wrote the first draft, so one of the biggest changes was realizing that it can’t take half the book to have inciting events happen. When I get reviews now that complain about slow pacing, I’m like, ‘You have no idea; it could have been so much worse.’ Although I do think pacing is so much in the eye of the beholder, and it depends on where you’re coming from. I love YA fantasy, but people who come from reading that do have certain expectations about how fast things get going. Maybe if you were coming from, oh, you know, say late Victorian literature, you wouldn’t necessarily feel the same urgency.

“The other big issue with my early drafts of The Ten Thousand Doors of January was the emotion between January and her parents. It was sort of flat and insignificant, because isn’t that how the parents in kids’ books always are? Distant figures who die conveniently so their kids can have adventures? But then somewhere in the middle of writing it I had my oldest son, and I felt the whole story skewing in my head. In the next draft the book within a book was no longer just a fun adventure-y mystery – it was a letter, and an apology, and the whole thing was much more about homegoing than I’d thought.

“My new book, The Once and Future Witches, has the same publisher, Orbit, and the same editor, Nivia Evans. She’s fantastic. I do have a thing for witches. Who doesn’t have a thing for witches, though, honestly? I started to slowly realize that when we say ‘witch,’ we mean almost any version of a femme-presenting person with magic powers. It’s interesting how that’s almost treated like a subgenre within fantasy when… that’s what fantasy is! It is people with magic powers – we just give it a special label when it’s women with magic powers.

“In the first draft of this book, there were only 20-something chapters, and it felt very reasonable to have each chapter open with a spell. I thought, ‘Twenty chapters, of course there will be enough spells for that in the book,’ and then in the second draft there were 42 chapters, and I thought, ‘Oh, no.’

“Getting the tone right was one of the hardest things about The Once and Future Witches. With The Ten Thousand Doors of January, I always knew what kind of tone I was going for, because I knew what set of literature I was coming from early on. The main character was writing from first person and had read a bunch of boys’ adventure stories and 19th-century lit, so I was allowed to have that slightly precious Victorian children’s fiction tone throughout. I know that tone very well, and have decent ear for it, so it wasn’t that hard. With The Once and Future Witches, I was writing in third person for the first time, and it felt like there were no rules, and that was terrifying. It took me a lot longer to realize that I was drawing on a combination of Western fairy tales and oral folklore, and that I could use the repetition and alliteration and other tools used in the fairytales that I like so much. Once I knew the tone I was trying to hit, that helped so much with rewriting the book.

“The elevator pitch for The Once and Future Witches book is actually how I sold it. It’s a three-word pitch: ‘Suffragettes, but witches!’ My editor said, ‘I like it,’ and I said, ‘Great!’ Then I had a year to fully experience the distance between something that is a good pitch and something that is a good story, which is huge, actually. The novel ended up not exactly being ‘suffragettes, but witches,’ but rather an alternate vision of the American women’s suffrage movement, focused on three sisters trying to turn the women’s movement into a witches’ movement.”

Interview design by Francesca Myman.

Read the full interview in the January 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.

I periodically have a nightmare that one day a decade will arrive in which there are no writers coming up, no would-be writers, no writing writers, no new writers at all. The interview with Alix Harrow takes away the nightmare for at least a few more nights/years. Thank you, and I will look for your books!