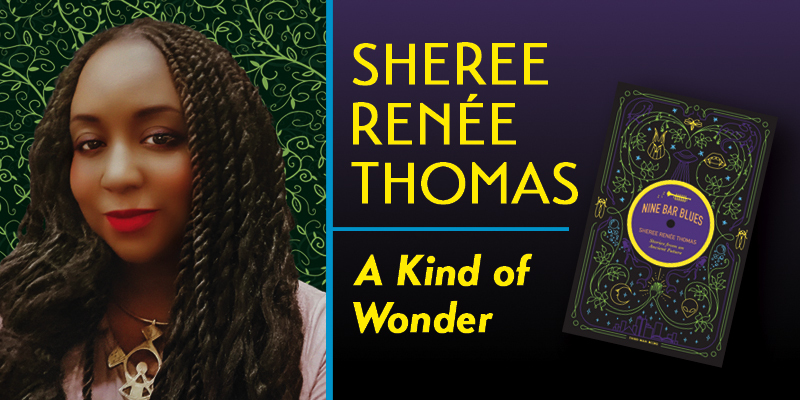

Sheree Renée Thomas: A Kind of Wonder

Sheree Renée Thomas was born September 30, 1972, in Memphis TN. Her father joined the Air Force, and her family traveled extensively. After spending 20 years in New York, she has now settled back in her hometown.

Thomas is best known for her work as an editor, including Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora (2000) and Dark Matter: Reading the Bones (2004) – both won World Fantasy Awards, and Thomas was the first Black writer to win a WFA. She has also edited genre magazines including Apex and Strange Horizons. She was recently named the new editor of F&SF, taking over from outgoing editor C.C. Finlay starting with the March/April 2021 issue.

Thomas is a prolific author of short fiction and poetry, and began producing work of genre interest with “How Sukie Cross de Big Wata” (2003). Some of her work is collected in Shotgun Lullabies: Stories & Poems (2011), Sleeping Under the Tree of Life (2016), and the new Nine Bar Blues: Stories from an Ancient Future (2020).

In addition to writing and editing, Thomas has worked in the book publishing industry, as a bookseller, and as a writing teacher.

Thomas was a guest of honor at the 2019 World Fantasy convention, and in 2020 she was a World Fantasy Award finalist in the special award, professional category for her contributions to the genre. She will be guest of honor at WisCon 45, to be held in May 2021 in Madison, WI, and she will also be a special guest at Boskone 58’s virtual convention, to be held February 12-14, 2021. She is also appearing as a special guest at DisCon III, the 79th World Science Fiction Convention, to be held August 25-29, 2021 in Washington DC, where she will co-host the Hugo Awards ceremony with Malka Older.

Excerpts from the interview:

“Moving around a lot has impacted my editing and writing, because I was met so many people from different places, even as a small child. I understood that the world was much larger than my front porch. I didn’t make strong attachments to people early on, because I would always leave them. I would have a great friend I would love, and then we wouldn’t be there anymore. I had to get used to this kind of nomadic experience early on, and accustomed to the codeswitching that was all around me. Americans are used to thinking in one language, and we’re thinking of English, right? But a lot of Americans have other mother tongues, other ways of speaking. Even if English is your mother tongue, there are regionalisms. I always jokingly say, if you’re from Memphis, I know which part of town you’re from by how you say certain words. I know your class sometimes as well.

“I can’t speak for all the other communities in the region, but if you’re a Black Southerner, you’re accustomed to people thinking they know what you have to say already because of your accent. They’ve seen all these different versions of ‘Southern’ in popular media, mostly wrong versions on television and in movies, and so they think they already know who you are. That stereotyping may be true for all Southerners, Black or otherwise. The South is underestimated but, as André 3000 said, ‘The South has something to say.’ The other thing on top of that is that, when you’re Black, it’s as if you must prove you’re intelligent by speaking Standard English, because people assume that if you speak any other regionalism or any version of vernacular, then you are every stereotype they’ve ever seen in any pop cultural version of that. Codeswitching can open doors for you – or close doors sometimes, if you’re not able to gracefully and fluently codeswitch your accent.

“I remember being so surprised when I moved to New York. First of all, New York is a city of mother tongues. And I was living there when I finally realized Bugs Bunny was from Brooklyn! I went there to be a writer and I needed a day job, so my day job was working for Forbidden Planet at the bookstore, back when it was across the street from The Strand. I worked at a publishing company as well. They paid us horribly. New York was still set up for you to be a trust-fund baby coming from the Ivy League. Maybe you go shrimp trawling during the summer or do something else to have an adventure, give yourself some street cred and add to your writer’s bio. So you come to New York and work for nothing at a publishing company and get your free books and keep it moving. That was still when they had cocktail parties and wined-and-dined their authors, so we would wait for whoever was coming in that week and see if we could get some shrimp and wine and cheese, and ogle the agents and famous writers and listen to shop talk, and then go back to our cubicles. I wrote jacket copy, did copyediting, proofreading – almost anything you can think of to make additional money to add to the ridiculously low salaries publishing offered us, including working at the science fiction bookstore, which I loved. After all, I met Michael Jackson there. I started in multicultural and women’s fiction, editing Regency novels and romances and other fiction and memoirs. I worked as a ghostwriter, too. There was rarely more than one Black person at an imprint – most Black people were working in the basement in the mailroom, and God forbid if there were more than two of us in the elevator. It was treated as if there was an uprising happening in the fields.

“Writing is just a symbolic representation of what we do with our voices – storytelling is an oral tradition. That’s why it’s not enough just to print a book and publish it. We love audiobooks and we love to hear the writers read their work – we want to experience it that way. That creates a sense of wonder for us. Whether you write with vernacular or in your native tongue, it’s all valid, because you’re telling universal stories. I had to learn to overcome the default messaging that suggests otherwise. If, as a Black, Southern woman reader, I can find a way to connect to so many stories by other writers whose works don’t center me, then I know others can do the same when they encounter works that place them on the margins. I had to work when I was reading The Lord of the Rings and other works that have invented languages in them, but it’s not that hard to get into the rhythm of a person’s writing and get the story they’re telling, because it’s all in the context of the action anyway. I absolutely love and enjoy works like Celeste Rita Baker’s, or some of the language in the beautiful stories and novels of Nalo Hopkinson, and I think that we should be reading, translating, and publishing more works that challenge the defaults of writing and storytelling that we have been taught. It’s an interesting challenge, trying to translate mother tongues into other languages. Whole codes, histories, and social values are contained in them, and those worlds, those special ways of seeing don’t always come through. I was in a collection called Afrofuturo(s) from a Spanish publisher, and they translated our stories, but for my story, ‘The Dragon Can’t Dance’, there is some vernacular language, because it’s a science fiction tale about B-girl choreographers and dancers. They’re performing at Goat Park doing their thing, and the editors wanted to convey that sense of another tongue that’s not just the King’s Spanish. The translators used another rural Spanish dialect to create that effect for their readers, and I appreciated the effort to do that.

“I had to make a conscious decision about how to write as an emerging author. When you’re pursuing writing as a career, you hear a lot about what constitutes ‘real writing,’ and what is publishable. You’re supposed to write dialogue like Elmore Leonard – or whoever is the latest literary darling. Only certain characters from certain social classes are worthy subjects for specific kinds of stories, and not everyone is considered important enough to have adventures. Everyone else is set dressing. You don’t usually get told that overtly, though I have been in situations where it was said overtly. For me, the kinds of stories I wanted to write, I didn’t see often in other places. I wondered, if I was given a gift and talent and an ear and a voice and a vision and imagination that is uniquely my own – why would I filter that through a lens that isn’t natural to me? Also, that other, more traditional kind of writing doesn’t need my assistance. There are literally hundreds of thousands of books that are written from these other mainstream perspectives – why should I take my art and bend it to fit another tradition that doesn’t match mine or serve me? I need to speak for me, observe and record the world as I know it, filtered through the lens of my imagination. That’s what I had to do, even in non-white spaces.

“I remember being a student when I first moved to Harlem. My mentor was Arthur Flowers, the novelist, who was a professor in the MFA program at Syracuse for many years – he recently retired. One of the conversations we had was about how, if you’re going to write about our culture, especially using vernacular dialect, you need to create a balance so that readers are invited into the space and feel comfortable there, and can follow your rhythms. You can’t exactly replicate what people really say, because that might be too challenging for readers to follow. You give them an approximation of the language so they get a sense of it, just enough so they can hear the other music, and then they can follow and dance with you in the storytelling. It was important to get that technique suggestion and that permission from him, as he was a fellow Memphian and a beautiful writer whose work, Another Good Loving Blues, I deeply admired.”

Interview design by Stephen H. Segal.

Read the full interview in the December 2020 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.