Paul Di Filippo Reviews In the Shadows of Men by Robert Jackson Bennett and Dispersion by Greg Egan

In the Shadows of Men, Robert Jackson Bennett (Subterranean 978-1596069879, 120pp, $40,00, hardcover) August 2020.

In the Shadows of Men, Robert Jackson Bennett (Subterranean 978-1596069879, 120pp, $40,00, hardcover) August 2020.

Tachyon Publications. PS Publishing. NewCon Press. Subterranean Press. Four always reliable and stout bastions of the novella, that in-between-lengths type of fiction that offers the advantages of the short story (quickish reading time and lesser investment) and the advantages of the novel (space for complexity and depth). Win-win, for writers, readers, and publishers!

Let’s have a gander at two new offerings from the last-named press.

Although today he is justly famed for his fictional fantasy worlds that depict independent subcreations (in the Tolkien sense), Robert Jackson Bennett began his career a little closer to consensus reality, and closer to horror. In early novels like The Troupe, American Elsewhere, and Mr. Shivers, Bennett limned naturalistic milieus inhabited by spooky weirdness. It’s this mode that he returns to with In the Shadows of Men.

The setting is Texas, a small town named Coahora. (With the Spanish word for “now,” ahora, embedded in the imaginary name, I read suggestions of “shared times,” co-now, which proves to be very thematically accurate.) Our narrator is never named, but is referenced as “little brother” by the fellow he is arriving to meet: Bear Pugh, his older sibling. Bear, a lowlife with a conscience and good intentions, has bought an abandoned motel and plans to make a killing by renting it out to workers in the fracking industry. He’s enlisted his brother as partner, and Little Brother has taken the assignment for lack of anything better, since his marriage has just fallen apart.

It turns out that the motel was once owned by a distant relative, Corbin Pugh, long dead, but who appears to have been an utter bastard. As the brothers start to labor over the building, they learn unsettling things. The local sheriff reveals that Corbin Pugh ran the place as a whorehouse. And the brothers discover on their own a secret underground chamber of nefarious mien. Then commence the supernatural happenings: the wailing voices of women, the shambling depredations of a manlike ghost. And when Bear begins acting more like Corbin than like himself—that’s when Little Brother has to choose a path either to damnation or an excruciating salvation.

The primary allure of such a tale is of course the occult doings, the level of creepiness and suspense that the author can attain and transmit. Bennett succeeds a thousand percent along these lines, despite deploying freshened-up horror tropes that have a certain familiarity. But actually, the horror spine of the story also functions as an armature from which to hang a number of other themes: familial responsibility and guilt; societal indifference to evil; an individual’s decision to strive or abandon hope; capitalistic practices that inure us to suffering; neglect of society’s marginal and cast-aside individuals. These strong but subtly rendered issues add much depth to the tale. Along of course with the deftly rendered and tangible scrubland setting, full of lyrical melancholy.

The coda to the events, wherein Little Brother muses—“A dream of finding some blank stretch of forgotten earth unscrolling beneath the heavens and thinking, how can I make this mine…”—ties this novella into the great tradition of Texas Ambition Tales, like the famous film Giant (1956). Except with added spooks!

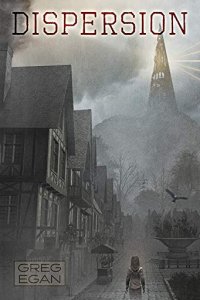

Dispersion, Greg Egan (Subterranean 978-1596069893, 160pp, $40.00, hardcover) August 2020

Dispersion, Greg Egan (Subterranean 978-1596069893, 160pp, $40.00, hardcover) August 2020

One is not initially prepared for Greg Egan—master of hard-edged speculative math and physics—to create a setting and plot that subliminally conjures up the village in Hope Mirrlees’s Lud-in-the-Mist, and yet that’s just what he’s done with Dispersion. As in Mirrlees’s fantasy, the six villages—we focus on two, Ryther and Myton—that constitute Egan’s story-telling venue are under assault, but not from outsider fairy fruit. In their case, they are being attacked from within, as their own bodies betray them by literally casting off parts. (So in a sense, this book, along with a couple of other recent titles, is a pandemic novel, proleptic of our current fix.) But Egan’s science-loving bent still emerges, even though his villages exist with hardly anything we would call technology, except for some rudimentary medical knowledge and technics. His emphasis on science emerges in two ways: first, in the weird yet utterly coherent biological schema by which his humans exist. And second, in his depiction of the scientific process, as exemplified in our heroine, Alice.

First, the schema: there are six types of matter in Egan’s universe, and six types of humans that can interact with each category of matter. A particular food, for instance, that nourishes one “fraction” is useless or hostile to another. (A logical aspect of this segregation is the invisibility of one tribe to another—until such time as an outsider is assimilated by prolonged contact—which allows Egan to pull off some nice effects a la Miéville’s The City & the City.) Some substances, such as stones, are perceptible in common.

With his typical ingenuity and meticulousness, Egan makes the explication and development of this novum central to the intellectual excitement of the book.

And the unraveling of the mysteries of their existence is carried forth mainly by our protagonist, Alice, a young woman who is a journeyman medical researcher. Born of a Ryther mother and a Myton father (and how alien sperm can interact with alien egg to make an embryo assumes metaphysical dimensions), Alice is dynamic, dedicated, and unrelenting. Egan paints a fully enlivened portrait of her, and gives us ones for all the other characters as well, including the math genius Timothy, who is dying of the Dispersion, but who manages to put Alice on the trail to a solution. Her mad and impetuous “challenge trial” at the end provides some excruciating suspense.

Egan’s belief in the scientific process reminds me of a similar display in John Brunner’s The Crucible of Time, where planet-bound aliens had to strive to unriddle the universe they could barely discern. In fact, Egan explicitly has Alice use a metaphor comparing her researches to trying to study the stars through a fog.

A last angle that Egan fully exploits is the human prejudices and hatreds and competitiveness that arise amongst clans formed by ultimately meaningless and arbitrary distinctions. (A good similar working-out of this theme was Rupert Thomson’s overlooked Divided Kingdom.) So the novella also functions as a parable of all those fault lines in our own society: racial, sexual, ethnic or what have you.

In the end, Dispersion forms a tasty meal no matter what “fraction” you belong to.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.