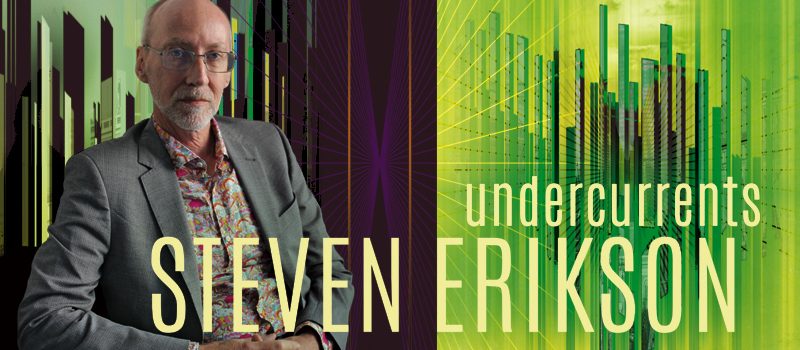

Steven Erikson: Undercurrents

Steve Rune Lundin, who writes fantasy as Steven Erikson, was born October 7, 1959 in Toronto, Canada, and grew up in Winnipeg. He trained as an anthropologist and archaeologist and is a graduate of the famed Iowa Writers’ Workshop; his thesis, a collection of linked stories, became his debut publication, A Ruin of Feathers (1991), written as Steve Lundin. He followed that with two more collections and debut novel This River Awakens (1998), also as Lundin.

He is best known, however, for his fantasy work under the Erikson pseudonym, beginning with World Fantasy Award finalist Gardens of the Moon (1999). That launched his sprawling Malazan Book of the Fallen epic fantasy series, which ran for nine further volumes: Deadhouse Gates (2000), Memories of Ice (2001), House of Chains (2002), Midnight Tides (2004), The Bonehunters (2006), Reaper’s Gale (2007), Toll the Hounds (2008), Dust of Dreams (2009), and The Crippled God (2010). A prequel series, the Kharkanas Trilogy, began with Forge of Darkness (2014) and Fall of Light (2016), with concluding volume Walk in Shadow forthcoming. He published several novellas in the Tales of Bauchelain and Korbal Broach, set in the Malazan universe, starting with Blood Follows (2002), and including The Healthy Dead (2004), The Lees of Laughter’s End (2007), Crack’d Pot Trail (2009), The Wurms of Blearmouth (2012), and Fiends of Nightmaria (2016), plus omnibus collections. A new series set in the Malazan world, the Witness Trilogy, is forthcoming. He created the setting with Ian Cameron Esslemont, who has also published work in that universe.

Erikson’s other books include novellas The Devil Delivered (2005), Fishin’ with Grandma Matchie (2005), and Revolvo (2008); affection- ate Star Trek parody Willful Child (2014) and sequels Willful Child: Wrath of Betty (2016) and Willful Child: The Search for Spark; and first contact novel Rejoice: A Knife to the Heart (2018). Some of his genre short fiction was collected in The Devil Delivered and Other Tales (2012).

Erikson has lived in the UK and the US, but returned to Canada in 2012, where he lives with his wife, Clare Thomas, married 1995; they have one son.

Excerpts from the interview:

“My pen name came about because my first novel was contemporary fiction, called This River Awakens, from Hodder & Stoughton. That came out under my real name, Steve Lundin. When I sold my first fantasy novel, Gardens of the Moon, to Transworld, the people at Hodder & Stoughton called my agent and said, ‘Because we’re publishing him as a contemporary fiction author, we don’t want you to use the same name for his fantasy – we want him to come up with a pseudonym.’ I chose my mother’s maiden name, because she was probably my biggest influence in terms of being a voracious reader, reading all kinds of genres – I grew up with all these books always around. She didn’t live long enough to see me published, and to honor her memory I chose Erikson. The follow-on to that is amusing, because Gardens of the Moon did quite well, and I signed for nine more books. Then Hodder & Stoughton called my agent and said, ‘We changed our minds about him using a pseudonym,’ and we said, ‘It’s too late now!’

”The curious thing is, you end up assuming a different persona when you’re in the public eye under a pseudonym as opposed to under your own name. I have two personalities – at least; who knows, I may have multiple. But I definitely have two: one is the professional Steven Erikson, and the other one is the guy who watches hockey games and sleeps in late. I don’t think the different personalities show up in the way I write under different names, just in the public persona. In a way you’re playing a role, but at the same time I’ve endeavored to be as honest and forthright with my readers as I possibly can – and as generous, because they put the time in to read these things. It is a different kind of interaction with people, and allows me to keep an element of professionalism. Because of Steven Erikson, Steve Lundin does not have a swelled head – let’s put it that way. Readers are responding to that persona. On my Facebook pages and all the rest, I always bear in mind who the audience is, as opposed to a collection of friends. So it is a different approach.

”Growing up, there were always books in the house – the place was full. My mother loved nature as well, so we had massive collections of the Time Life books. I still have a whole bunch of them sitting at home. I think that’s a huge thing. When we were living in England with our son, who was seven or eight at the time, there was a school program to get the kids to read for 30 minutes a day. You had to fill out a little form and sign off, and we refused to do it, because you cannot force somebody to read – but if you leave enough books lying around, children will pick them up. If there are no books in the house, then it’s less likely that they get into reading.

”Frank Frazetta introduced me to the genre. I thought I was going to be a comic book artist. I’d been pushed through a number of extracurricular art courses at the Winnipeg Art Gallery by my high school, and so I was heading in the direction of illustration, painting, and all of that. I was at the book department in Eaton’s, a big department store in Winnipeg, and suddenly I saw this book cover by Frank Frazetta – I think it was ‘Conan Man Ape’? A Conan book, the Lancer edition, and it just floored me. This guy could paint. It was like nothing I’d ever seen. I promptly started buying every book that had a Frank Frazetta cover on it, and those books tended to be Robert E. Howard and Edgar Rice Burroughs, because the Burroughs books were being reissued by Ace at the time, and they were all appearing with fabulous Frazetta covers. And since I bought the books, I figured I may as well read them. I went from hardly reading anything apart from the occasional Hardy Boys book, straight into Robert E. Howard and Burroughs. I was 11 or 12.

”I didn’t even think about fiction writing until I was maybe 21 or 22, when I did a short story for a local contest and came in second place, and I thought, ‘Okay, maybe I can do this.’ A friend of mine and I were running the Faculty of Arts student newspaper. We only took that job because we wanted the office, and we used to lock the door with a note on the outside saying ‘Go away’ – we spent our spare time farting around in that office, drinking coffee spiked with Amaretto before class. It was a fun time. I was writing editorial stuff and local news on the university, department, and faculty. And writing polemics, as one does in their early twenties. Public service announcement stuff would come in our mail, and there was a note about a short story contest. I thought, ‘All right, I’ll see what I can do.’

”I had to take extra courses to finish my degree, and one of them was a creative writing course on Wednesday nights. What I didn’t notice was that the instructor was specifically looking for poets. His name is George Amabile, a very good poet in Winnipeg. I tried writing some of this poetry stuff, and I got called into his office. He basically said, ‘What are you doing in this class?’ I told him, ‘What I really want to write, and what I’m working on right now, is a fantasy novel.’ He said, ‘Okay, you don’t have to come to class. Keep writing, and we’ll meet maybe once a month and you’ll give me an update on where you are in the book. If you can get a big chunk of it done, I’ll look at it over the summer.’ That was the most important single moment for my writing career. By April I handed him a 700-page novel. It was not related to Gardens of the Moon – I was in my twenties, and I’d sit down at my tiny electric typewriter with correction tape on it, and I just pounded this thing out every night. Amazingly, he sat down over the summer and edited the whole thing. I met with him in the fall in his apartment and we went through it page by page. I’ve since come back to him and said, ‘What you did was extraordinary.’ I could not have imagined going to that effort. At the end of it all, he looked at me and said, ‘I could see you as a science fiction writer or a fantasy writer.’ That always stayed with me. I’ve long since lost the manuscript, and it was rubbish anyway, but I completed a novel – that was the most important thing. When I’m teaching young students or beginning writers, or doing signings, sometimes people ask for advice, and my one piece of advice is: ‘Finish what you start.’ There is nothing more important.

”I left a master’s program in archaeology to join a writing program at the University of Victoria. It was a relatively new creative writing program, and the instructors were quite fresh – they weren’t burned out yet (which invariably happens). The timing was really good for me. I learned almost everything I know about the craft of writing there, but it was primarily focused on short stories. Then I went to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where I submitted the prologue and a chapter of my contemporary fiction novel This River Awakens. I was in the workshop being taught by the department head, Frank Conroy, and he really trashed the chapters. He called me into his office later that week and basically said, ‘I don’t see you ever becoming a published writer. I don’t know why you’re here.’ Wow, okay. That got my back up. It was like, ‘Fuck you, Frank.’

”When I look back at Iowa, I made one very good friend, the writer Chris Offutt. We still see each other. My thesis was my first published book, a collection of stories, which is now out of print and unavailable. Other than that, Iowa was just two more years in which to write – that’s what I got out of it. These were not genre workshops. Joe Haldeman broke all the rules when he wrote The Forever War at Iowa, but he was a few years before Conroy. When I was there, everybody wanted to be Raymond Carver, but none of them had the life experience of Raymond Carver. You had this superficial glibness of language, but no subtext at all. I write to subtext. That’s where everything bubbles up from. The emphasis at the time was on clarity of language and that Carveresque minimalist style, but I was playing around with mythological undercurrents. I eventually gave up on writing what I would call ‘serious fiction’ there, and ended up writing over-the-top, tall-tale, magic-realist stuff and just had fun with that. I wrote one horror story that ended up in a ‘Best Of’ anthology many years later. By and large, I did not get that much out of Iowa in terms of learning the craft of writing. A lot of what I saw was stuff I did not want to do. The two years in Iowa City were wonderful, though. It’s a great place. We partied a lot. The fiction students played baseball against the poets – and we lost every time. The poets just kicked our butts. The social side was fabulous, and I loved Iowa City. This tiny city, but it had fantastic concerts and events, so it was great to be there.

”Because we write in isolation, we can feel very isolated. You can have friends at home, but they’ve got their 9-to-5 jobs, and it’s a whole different world. I’ve always felt immensely isolated, and I was kind of faking it when I was in Iowa, because I was writing stuff that I eventually moved away from. I had impostor syndrome to some extent in that program. One of the great things about conventions – as I discovered much later – is that you come away no as isolated as when you arrived.”

Interview design by Francesca Myman. Photo by Arley Sorg.

Read the full interview in the July 2020 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.