Jordan Ifueko Guest Post–“The Watchmaker Author”

When I got serious about writing in my teens, my literary opinions involved a lot of eyerolling.

Black and white false dichotomies attracted me, as they do many thirteen-year-olds eager to become Serious Artists™. One creed I held to be especially dear was that fake writers treat stories like games of pretend, and real writers remain conscious of their task—making art—at all times.

Adulthood shrunk my head a few sizes. I learned that terms like fake and real held no value beyond cruel verbal gatekeeping. Still, I clung to some of my teen suspicions. I had noticed how easy it was for me and my peers to get stuck in a loop of character trivia and worldbuilding, often without ever finishing a project. “Did you get any writing done?” “Sure! I mean, sort of. I filled out seven character worksheets! Wanna know what my protagonist keeps in all her pockets, the names of her twelve pet mice, and the fan art I made of each one?”

I cringed when writers referred to their characters as their children: independent creatures who constantly surprised them. My eyes glazed over at comments like, “You’ll never guess how much trouble Prince Blimothy has been this week. I tried to make him kiss Queen Blondabelle, but he just laughed at me and said, ‘NOPE. I’m actually in love with Rogue Brunessica!‘”

People always made these comments with what struck me as feigned helplessness, and even a little narcissism. Did we have to think of ourselves as handwringing creator gods? Why couldn’t we just, you know, be honest? We made stuff up. Sometimes, we changed our minds about the things we made up. Our characters didn’t “surprise” us; they did precisely what we wrote them to do. Their minds changed only when our outlines did.

Sound boring? Whelp, I sniffed, that’s Serious Art for you! Surely Charlotte Bronte didn’t regard Jane and Rochester as mystical imaginary friends. Surely, she had shaped them like a master sculptress, bending their thoughts and actions to her story’s theme.

Sound boring? Whelp, I sniffed, that’s Serious Art for you! Surely Charlotte Bronte didn’t regard Jane and Rochester as mystical imaginary friends. Surely, she had shaped them like a master sculptress, bending their thoughts and actions to her story’s theme.

But as my writing style matured (and my ego shrunk), I stumbled into a strange roadblock. Many writers complain of finding it easier to write their side characters, who are quirky and full of personality, than to write their protagonists, who are flat and shell-like in comparison. I struggled with the opposite problem: my protagonists had rich inner thought lives that came easily to me, while my side characters felt derivative, like facades with no dimension. At last, I realized why: I had based all of my protagonists on myself. Of course there were some differences—an assassin here, a goddess there—but their values and problem-solving strategies were more or less my own. What if I stretched myself? What if I purposely wrote a protagonist with traits opposite to mine?

The moment I tried approaching characters this way, a new ingredient brought my stories to life: empathy. In creating distance between myself and each character, my imagination had to work double time. I found myself using tools I’d shied away from before—character playlists, visual aids and Pinterest boards. Once I established the boundaries of this Not-Me’s mind, and the foreign rules by which she made decisions… my work took on a living, organic feel. No longer was I a master sculptor shaping clay, but a sweating gardener, coaxing vines toward the light, but knowing that in the end, they must find their own way.

Isaac Newton once advanced the theory of a Watchmaker God: a deity who made the world, but who then let it run with either (1) no interference or (2) interference so consistent with the rules of nature, it would seem he did not interfere at all. In a way, I think stories require us to be Watchmaker Authors—both a sculptor and a gardener. The best fantasy worlds are equally defined by rules as they are imagination. Once we lay the scaffolding of a place or a person, we can’t betray that framework—consistency makes a world believable. But rules can limit us in ways that make us transcend the limits of our experience. We can’t make Blimothy kiss Brunessica because the plot needs him to, or because we’re attracted to Brunessica, but because he would. And if he wouldn’t, we have to achieve the plot another way.

I’ll never think of myself as a handwringing parent-god. But I have grown to see characters as people I’m coming to know, rather than as vessels on a potter’s wheel. And who knows?

Maybe Charlotte kept imaginary friends after all.

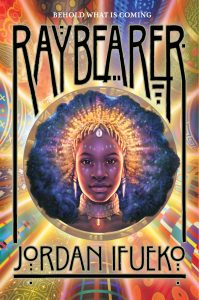

Jordan Ifueko is a Nigerian American writer who grew up eating fried plantains while reading comic books under a blanket fort. She now lives in Los Angeles with her husband and their collection of Black Panther Funko Pops. She can be found on Twitter and Instagram at @JordanIfueko. Raybearer is her debut novel.