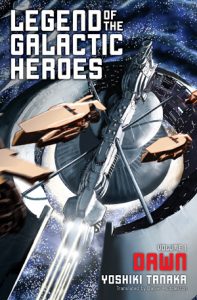

Rachel S. Cordasco Guest Post–“Legend of the Galactic Heroes”

Yoshiki Tanaka’s Sieun Award-winning Legend of the Galactic Heroes (LotGH) series is simultaneously a work of science fiction (specifically space opera) and an in-depth historiography. Multiple texts exist within its two-thousand-plus pages, with a single unnamed narrator drawing on (fictional) memoirs, autobiographies, and other histories in order to craft their own interpretation of the galactic conflicts of the thirty-sixth century. Originally published in Japan between 1982 and 1987, LotGH was finally published in English between 2016 and 2019, thanks to Haikasoru’s editors Nick Mamatas and Masumi Washington and three talented and dedicated translators: Daniel Huddleston (Volumes 1, 2, 3, and 7), Tyran Grillo (Volumes 4, 5, and 6), and Matt Treyvaud (Volumes 8, 9, and 10).

During this nearly-thirty-year gap between the series’ publication in Japanese and then in English, Tanaka’s story has been spun off into manga and an anime series, which both Japanese and Anglophone audiences have enjoyed. And like many other speculative Japanese texts that have eventually made their way into English, manga and anime versions have often come first to Anglophone audiences, thus influencing how a certain portion of fandom has embraced (or not) the publication of the novels in translation. As someone who doesn’t speak or read Japanese and never consumed anime or manga, I represent yet another slice of fandom that knows Tanaka only through English translation, which certainly influences how I’ve approached LotGH.

Tanaka’s story itself is grand in scale: ten novels written over a five-year period about several years of war between a mighty empire and a multi-planet alliance—a war that takes place 1,500 years in the future and spans millions of light years. It’s not too much of a stretch to read LotGH as a kind of science-fictional response to Edward Gibbon’s six-volume History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776-1789), which told a story about Western civilization from the height of the Roman Empire to its dissolution with the fall of Byzantium in 1453. And while Tanaka is far from the only genre author in any language to model a series on a work of global history, he is unique in that his books were written in Japanese, with most characters bearing German names, all of which has found its way into English. It is this fusion of Eastern and Western approaches to history, language, and storytelling that intrigues me most of all.

LotGH is a multi-layered, multi-textual work because it tells different stories on multiple levels that serve different purposes. The first (or surface) level is that of the basic plot, in which the Galactic Empire battles the Free Planets Alliance, with the brilliant leaders Reinhard von Lohengramm (who becomes Kaiser of the Lohengramm Dynasty) and Yang Wen-li (brilliant military strategist for the Alliance) squaring off again and again in their respective quests to unite or liberate humanity (which, in the thirty-sixth century, numbers far into the billions).

On the next level is the narrator’s metatext, in which they cut into their own story (about von Lohengramm and Yang’s exploits) to comment (often acerbically) on how other historians have interpreted the same events that this narrator is interpreting for us. This constant reference to other historians and their apparently flawed analyses suggests that the narrator as an (academic?) historian who is writing even farther in the future. It’s the act of keeping this timeline in mind and then simultaneously thinking about where that places us as readers in relation to the story that sometimes gives me a (not unpleasant) headache.

On yet a deeper level, we are invited to read this series as a carefully-crafted text that comments on the act of writing history and the differences and similarities between “histories” and “legends.” In the Anglophone world of the twenty-first century, a work of history generally signifies a relatively objective text that tells its readers about certain important events and people. Most of us are aware, nevertheless, that historical objectivity is an illusion and that historians, as humans first and researchers second, necessarily bring their own biases and experiences to their work. Tanaka explores this tension between “objective history” and unverified legend in his series’ very title (as rendered in English): Legend of the Galactic Heroes. A “legend” occupies an interesting liminal position, existing somewhere between history and folk tale. This word thus influences how we approach Tanaka’s story: we are asked to take all of the events with a grain of salt, even as we remind ourselves from time to time that the entire series is a work of fiction.

And yet, this story isn’t completely unrelated to anything in our world (what is, really?). As many readers and critics have noted, LotGH is based loosely on the European wars of the nineteenth century, which were bookended by the Napoleonic Wars (1800-1815) on the one hand, and the Wars of German Unification (1864-1871) and the Wars of Imperialism on the other. The German names of most of the characters in both the Empire and the Alliance suggest that Tanaka is drawing on the Prussian military culture that was fully absorbed into a newly-unified Germany toward the end of the nineteenth century. Because Tanaka’s narrator is writing from a future time (how far ahead of the Lohengramm and Yang era is unclear), they seem comfortable approaching the (his)story they tell from a perspective that is not too obviously biased (though the narrator does clearly favor democratic rule). Von Lohengramm, emperor of an autocratic government, is nonetheless depicted as an enlightened ruler whose tact, wisdom, and confidence leads him to treat his enemy (the Alliance) honorably. The Free Planets Alliance, on the other hand, is often wracked from within by corrupt, selfish leaders who take advantage of democratic rule to further their own political and personal aims. Thus while the series fundamentally prefers the Alliance over the Empire, it’s nearly impossible for readers to view the former as Good and the latter as Evil.

Ironically, Alliance military leader Yang Wen-li himself trained as an historian and maintains his desire throughout the series to retire from battle and write a history of his times. Of course, Yang’s death soon after his long-sought retirement cuts off the possibility of such a text, and leads us to wonder if the narrator was influenced by Yang’s aspirations. And yet, this narrator seems much less charitable than Yang, whose fragments of an unfinished history the narrator quotes throughout the series. Halfway through the final book in the series, Sunset, the narrator quotes from “fragmentary memoirs” written by Yang and edited by Julian Mintz (Yang’s ward and successor) in an effort to support the following argument: “Perhaps the military confrontation between Reinhard von Lohengramm and the forces of republican democracy was, at the individual level, in some sense a contest between a genius and a possessor of some close relative to genius. This is only true, however, when considered at the individual level” (118). Immediately after this paragraph comes a long quote from Yang’s fragment, which reads, in part, “Reinhard von Lohengramm was a foe of republican democracy in the gravest sense—not because he was a cruel and stupid ruler, but because he was just the opposite.” The series as a whole bounces between showing us how wide-ranging decisions are made by powerful individuals and how millions of men and women fight and die in the many battles between the Empire and the Alliance. This constant contrast between the named few and the unnamed masses underscores what Tanaka’s narrator argues is the timeless tension in humanity’s attempt to achieve the perfect form of civilization.

As translator Daniel Huddleston explained to me regarding his work on bringing four of the books into English, sentence-level translation questions could end up influencing how later books in the series were rendered. According to Huddleston, for instance,

“… the word “gyokusai,” formed from the kanji for “jewel” and “shatter” is used in several places to describe a suicide attack. I first encountered that term in LotGH, and didn’t know how broadly it was used outside of that series. Afterward, I noticed it popping up in other novels and in historical films and documentaries. The more I heard it, the more I started to realize that native readers are “hearing” the meaning of the term itself; not the meaning of the kanji. That is, they aren’t thinking of a warrior’s life ending with the beauty of a shattered jewel; they’re simply thinking about someone making a suicide attack run.”

Then there’s the phrase “各個撃破 (kakko gekiha),” which refers to destroying isolated groups of enemies one at a time. Since no brief English equivalent exists for this term that was used quite often, Huddleston needed to translate it slightly differently depending on context. It’s translation issues like these that reveal what a key part translators play in bringing a text from one language and culture into another.

Given that I’ve been writing about the metatextual nature of LotGH, I’m not going to explore the fact that the characters seem, at least to this reader, relatively flat and that Tanaka’s depiction of space battles are far more beautifully rendered than his sketches of character relationships. Ultimately, those are not Tanaka’s goals. A text cannot be all things to all readers, and Tanaka’s focus on large-scale questions of human civilization and history is clear from the beginning.

One particular strand in this ten-volume story that I wish would have been explored further involves the Church of Terra. A constant thorn in the side of both the Empire and the Alliance, this group of fanatics is bent on rolling back centuries of history to return the Earth to its glory days as the cradle of human civilization. A fundamental religious group, the “Terraists” blow up government buildings and assassinate (or attempt to assassinate) high-level politicians. Only a few members of this group get much plot-time, and I spent the entire series wanting to know more about how the Empire and Alliance thought about Earth, which has become a lonely backwater by the thirty-sixth century.

A remarkable series that Anglophone readers can now enjoy in novel-form, Legend of the Galactic Heroes will stand as one of the great accomplishments in the ongoing efforts around the world to bring great speculative fiction into as many languages as possible.

Rachel Cordasco has a PhD in literary studies and currently works as a developmental editor. She also writes reviews for publications like World Literature Today and Strange Horizons and translates Italian speculative fiction. For all things related to speculative fiction in translation, visit her website: sfintranslation.com.