Mr. Russell’s Neighborhood by Russell Letson

Let’s try a different metaphor for this annual make-sense-of-the-field exercise: a ramble through my science-fictional reading neighborhood, which is a virtual space instantiated from the manifold of all-the-books-published and distinct from the neighborhoods described elsewhere in these pages by my colleagues. As I have pointed out nearly every year of the 30 I’ve been writing these wrap-ups, my reading is not statistically or demographically or subculturally representative – it’s the most self-indulgent kind of nose-following, minimally directed pleasure reading with little attention to what’s-goin’-on or where-we’re-headed. So this summary is just a glance over the shoulder at the footprints in the snow. (Reader: Will I like these books? Me: Sure, if that’s the kind of thing you like.)

I’m not sure that it says anything about the state of the field (for that I look at my colleagues’ reading, out beyond my particular patch), but I did find a nice cluster of close-to-home novels that seem to air some of our current anxieties, directly imagining near-future, coping-with-looming-disaster scenarios. The most direct approach is Greg Egan’s Perihelion Summer, with its catastrophically accelerated climate changes – drought-ravaged, heat-withered landscapes and displaced populations – and its refusal to give in to despair despite the direness of the changes and the irrational behavior generated by the stresses.

Climate change also lurks in the background of Karl Schroeder’s Stealing Worlds, but the foreground emphasis is more socio-politico-economic, occupied by dislocations rooted in the rise of disruptive technologies and predatory economic practices. The novel’s armature is one of which I’m particularly fond: a chase thriller. That chase is also a tour of possible paths to restoration of social balance and stability, which makes the book more hopeful than its noirish cyberpunk ancestors. The thriller/crime-story also informs Christopher Brown’s somewhat darker Rule of Capture – the legal thriller, to be precise, with a tattered, stubborn public defender facing down an unholy alliance of security-state bullies and corporate crooks in a near-future America that’s been knocked sideways by natural and international forces.

Climate change also lurks in the background of Karl Schroeder’s Stealing Worlds, but the foreground emphasis is more socio-politico-economic, occupied by dislocations rooted in the rise of disruptive technologies and predatory economic practices. The novel’s armature is one of which I’m particularly fond: a chase thriller. That chase is also a tour of possible paths to restoration of social balance and stability, which makes the book more hopeful than its noirish cyberpunk ancestors. The thriller/crime-story also informs Christopher Brown’s somewhat darker Rule of Capture – the legal thriller, to be precise, with a tattered, stubborn public defender facing down an unholy alliance of security-state bullies and corporate crooks in a near-future America that’s been knocked sideways by natural and international forces.

Jack Skillingstead’s The Chaos Function uses the chase format to send its protagonist through a whole series of alternate-world, sliding-into-disaster scenarios, each one worse than the last, as unintended consequences unfold from each attempt to fix the last set of problems. It’s a more character-centric story than the others in this group, but the nightmarish possible worlds are enough to send a fellow under the bed to hide until it’s over. S.J. Morden’s No Way (the sequel to last year’s One Way) blends a crime/conspiracy story (or its aftermath) with a very hard-SF survival-on-Mars adventure, with both sides given a strong procedural treatment that allows them run at full power.

I try not to feel guilty about my pleasures (which are also sometimes my duties), but I do get the occasional twinge when I notice how much of my reading comes from series entries. Does this indicate lack of adventurousness on my part, a failure to pursue the New and Innovative – too much of The Same and not enough of Only Different? On the other hand, much of SF/F comes packaged that way – the field has a long and honorable history of multi-part series, extended narratives that work not only by repeating the pleasures of a familiar cast of characters or a setting or stretching out the narrative, but by extending and expanding its world(s) – of making the setting as important as the characters and plot. The question becomes not just “what will happen next?” but “what awaits around the corner or over the hill or lurks on the next planet?” (And anyway, to hell with connecting pleasure and guilt.)

James S.A. Corey has been doing this right along in the Expanse sequence, which tells a long, complicated, segmented tale that deploys a range of story types as its universe expands. The series has mixed and matched noir thriller, space war, ancient alien-technology, psycho-killer, planetary disaster, extraterrestrial pioneering, and a fistful of other types and tropes, and it approaches its end in the eighth book, Tiamat’s Wrath, a return-of-the-musketeers story tinged with a melancholy that is entirely the series’ own, compounded of many simples, from cosmic wonder to compassion to sacrifice. Alastair Reynolds is doing something similar in Shadow Captain, which not only continues to unfold its strange, millions-of-years-hence setting but shifts its emotional tone from the YA adventure of Revenger (2016) to something darker and less comfy as its protagonists start to grow up and find out just how strenuous and character-challenging a life of adventure can be.

Neal Asher seems determined to fit all of his outrageousness into one, ever-expanding future-historical framework, and he piles the conflicts and heroes and monsters and planet- (or reality-) busting technologies atop each other to build increasingly titanic constructions. The Warship not only ups the threats-and-destruction ante of earlier Polity-universe books but dumps in leftover conflicts and antagonists from whole cycles of five-million-year-old wars. Linda Nagata is doing something similar (millions of years of backstory, godlike/demonic powers unleashed, mind-numbing scales of space and time), if a bit more quietly, by revisiting the far-future, post-human setting of her Nanotech Succession novels (particularly Deception Well and Vast) with Edges: Inverted Frontier and its sequel, Silver, which in turn also connects to her 2003 novel Memory: post-humanity comes through the Singularity and meets its humanity on the other side.

C.J. Cherryh & Jane S. Fancher’s Alliance Rising is a kind of origins story for Cherryh’s Alliance-Union series (which is in turn embedded in an even larger future history), but I read as though it were a standalone, and its pleasures stood on their own: the sense of a close-textured working milieu, however spaceborne and star-traveling, with an economy and an environment and political system that impose limits on what a protagonist can do. The world of work also figures prominently in Ian McDonald’s more baroque and attitudinal Luna sequence – which I would argue is not a “series” at all but a sprawling three-volume novel, with the finale, Luna: Moon Rising, providing a clear closing of its complex, multi-threaded plot. McDonald really needed the space to unfold his story and its world, with its glories and pathologies and the vivid, scary, outsized characters that populate it. His YA-ish Luna-setting novella, The Menace from Farside, is not so much a prequel as a side project, a way of showing aspects of the cultural setting that would not fit comfortably into the scheme and modes of the larger work and its emotional intensity.

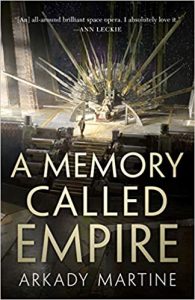

When there’s not an actual series in which to curl up, there’s the pleasure of finding work that belongs to the same extended genre-family, even when it is clearly its own individual (or even idiosyncratic) self. Arkady Martine’s A Memory Called Empire reminded me of a whole swarm of honorary-cousin works by Le Guin, Cherryh, Arnason, and Leckie, all of which insert anthropological thinking into narrative frames that a marketing manager might call “space opera” (even though the more appropriate label might be “planetary romance” or “First Contact”). In Martine’s case, an intrigue-thriller story framework is host to the real science-fictional core, as a puzzled visitor has to make sense of a whole complex world, taking an equally puzzled (and delighted) reader along for the ride. (Bonus: a sequel is promised. But it’s not a series yet.)

When there’s not an actual series in which to curl up, there’s the pleasure of finding work that belongs to the same extended genre-family, even when it is clearly its own individual (or even idiosyncratic) self. Arkady Martine’s A Memory Called Empire reminded me of a whole swarm of honorary-cousin works by Le Guin, Cherryh, Arnason, and Leckie, all of which insert anthropological thinking into narrative frames that a marketing manager might call “space opera” (even though the more appropriate label might be “planetary romance” or “First Contact”). In Martine’s case, an intrigue-thriller story framework is host to the real science-fictional core, as a puzzled visitor has to make sense of a whole complex world, taking an equally puzzled (and delighted) reader along for the ride. (Bonus: a sequel is promised. But it’s not a series yet.)

Ann Leckie’s The Raven Tower offers a similar mystery tour just for the reader, while also doing to the sword-and-sorcery genre what she has done to military SF: shake up the elements, rearrange them in surprising ways, and turn the damnedest set of inversions and givens into a smart and satisfying reworking. It is not explicitly marked as the beginning of a series, but the connectors and conduits that would support a sequel are clearly visible. Elizabeth Bear’s Ancestral Night is another series-in-the-making, an omnium-gatherum space opera that mashes together a great deal of big-screen action (alien encounters, chasing space pirates halfway across the galaxy and back) with intra- and interpersonal moral/social/political matters.

Now the inevitable unclassifiables, all variations on the retrospective. The editor of The Best of Greg Egan is Greg Egan, so I’m not going to argue with the selection of 20 stories from the whole of the writer’s career, except perhaps to think that the book could have been twice its considerable size and still deserved its title. Gary K. Wolfe took on the daunting task of characterizing a whole decade in compiling the two-volume American Science Fiction: Eight Classic Novels of the 1960s, which not only reminds us of some good work of a half-century ago but will provide convention panelists and blog writers with hours of fun as they second-guess his choices. (Not me – I’m cool with all of them.) And in Joanna Russ, Gwyneth Jones provides a career overview of a writer whose reputation as a theorist and commentator almost overshadows the considerable achievement of her fiction, an example of which is also represented in the Eight Classic Novels set.

Now the inevitable unclassifiables, all variations on the retrospective. The editor of The Best of Greg Egan is Greg Egan, so I’m not going to argue with the selection of 20 stories from the whole of the writer’s career, except perhaps to think that the book could have been twice its considerable size and still deserved its title. Gary K. Wolfe took on the daunting task of characterizing a whole decade in compiling the two-volume American Science Fiction: Eight Classic Novels of the 1960s, which not only reminds us of some good work of a half-century ago but will provide convention panelists and blog writers with hours of fun as they second-guess his choices. (Not me – I’m cool with all of them.) And in Joanna Russ, Gwyneth Jones provides a career overview of a writer whose reputation as a theorist and commentator almost overshadows the considerable achievement of her fiction, an example of which is also represented in the Eight Classic Novels set.

I can now hang my cardigan on its peg and start on my reading for 2020.

The shortest short list Mr. Russell can manage:

Rule of Capture, Christopher Brown

Tiamat’s Wrath, James S.A. Corey

The Best of Greg Egan, Greg Egan

Perihelion Summer, Greg Egan

The Raven Tower, Ann Leckie

A Memory Called Empire, Arkady Martine

Luna: Moon Rising, Ian McDonald

Stealing Worlds, Karl Schroeder

American Science Fiction: Eight Classic Novels of the 1960s, Gary K. Wolfe, ed.

Russell Letson, Contributing Editor, is a not-quite-retired freelance writer living in St. Cloud, Minnesota. He has been loitering around the SF world since childhood and been writing about it since his long-ago grad school days. In between, he published a good bit of business-technology and music journalism. He is still working on a book about Hawaiian slack key guitar.

This and more like it in the February 2020 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.