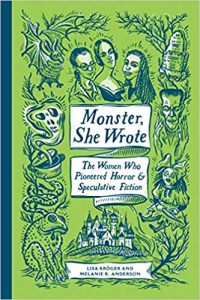

Alvaro Zinos-Amaro Reviews Monster, She Wrote by Lisa Kröger & Melanie R. Anderson

Monster, She Wrote: The Women Who Pioneered Horror and Speculative Fiction, Lisa Kröger & Melanie R. Anderson (Quirk Books 978-1683691389, $19.99, 288pp, hc) September 2019.

Monster, She Wrote: The Women Who Pioneered Horror and Speculative Fiction, Lisa Kröger & Melanie R. Anderson (Quirk Books 978-1683691389, $19.99, 288pp, hc) September 2019.

“Why are women great at writing horror fiction?” ask Lisa Kröger & Melanie R. Anderson in the Introduction to this excellent primer on women writers and the history of horror. One possible answer: “Maybe because horror is a transgressive genre…. In any era, women become accustomed to entering unfamiliar spaces, including territory that they’ve been told not to enter. When writing is an off-limits act, writing one’s story becomes a form of rebellion and taking back power.” This sentiment neatly captures the creative context of many of the works surveyed throughout this book’s nearly 300 pages, particularly in its first three sections, which cover roughly the 17th through the early 20th centuries. It also gives a sense of the book’s commendable aim: like the recent Lost Transmissions (2019), this volume claims a place for writers unfairly pushed to the margins of previous genre histories and illustrates, with one compelling example after another, that “the horror genre that readers love today would likely be unrecognizable without the contributions of these women.”

We begin with Margaret Cavendish, the first author discussed in the context of the genre’s “Founding Mothers”, and eventually, in the book’s concluding section, “The Future of Horror and Speculative Fiction”, we glimpse the works of many a contemporary writer, including Kelly Link, Helen Marshall, Carmen Maria Machado, Gemma Files, Caitlín R. Kiernan, Cassandra Khaw, Nadia Bulkin, Karen Russell, Tananarive Due, Jac Jemc, Nnedi Okorafor, Livia Llewellyn, Damien Angelica Walters, and Rebecca Roanhorse. Each of the book’s eight sections, though mostly fitting into an approximate chronological scheme, is theme-bound, so that in Part Two, for instance, we are spooked by “Haunting Tales”; whereas in Part Three we are seduced by the “Cult of the Occult”. These thematic sections are comprised of five to seven author-specific chapters. Each chapter, in turn, contains a short biographical summary, a one- or two-line excerpt, and a Reading List, comprised of “Not to be missed”, “Also try”, and “Related work” recommendations. I often found the latter to be the most intriguing suggestions (I’m going to be seeking out Eliza Lynn Linton’s “Christmas Eve in Beach House” during this year’s Yuletide festivities). But wait, there’s more! Some chapters also contain info-boxes with broader observations on genre, such as the one in the Alice Askew chapter, which talks about “Dynamic Duos”; i.e., famous writing partnerships.

You will find here, in short, hundreds of references to interesting books and stories, enough not only to remedy historical and bibliographical gaps, but to launch you on your own expedition into the desolate corridors and shadowy halls of horror history. Kröger & Anderson write in consistently engaging prose and display depth and breadth in their knowledge of literary matters. Besides demonstrating great synthetic acuity, they provide the fruits of original scholarship: they combed through countless pulp magazines in order to glean valuable information about their often obscure contributors. “Perhaps the weirdest tale,” they remark, in regards to writers like Mary Elizabeth Counselman, Gertrude Barrows Bennett, Everil Worrell, and Eli Colter, “is how we’ve managed to forget the women who created such amazing stories.” Indeed.

I was a bit perplexed by the editorial choice to include a book’s publisher in parentheses after its title. It felt cumbersome, and it wasn’t a format adhered to consistently, even in a single sentence (e.g. “Additional novels followed, including The Romance of the Forest [Hookham, 1791] and her most famous novel, The Mysteries of Udolpho, published in 1794 by G.G. and J. Robinson”). I do appreciate Kröger & Anderson’s informal tone and well-modulated irreverence. References to The Twilight Zone, Scooby-Doo, or even a comment about Amelia Edwards’s life being like something out of a Spielberg blockbuster, keep things light–which is welcome, considering the intrinsic darkness of the subject matter. That said, it didn’t all work for me. Observing, for instance, that Ann Ward was born in Holborn, England, “to a haberdasher and his wife,” they remark: “Doesn’t that sound like the most British thing you’ve ever heard?” Chuckle, chuckle, but still, that strikes me as a tad US-parochial, particularly for a book that consistently champions inclusivity of all stripes. The earlier comparison of Margaret Cavendish to a Kardashian, while perhaps of useful mnemonic value, was unconvincing. She “was acutely aware of her notoriety and cultivated her reputation as a celebrity,” note the authors. Fair enough, but Cavendish was also a deep thinker, a true social revolutionary looking to change the system, and a thoughtful artist.

Kröger & Anderson cover a phenomenal amount of ground with a light touch, exemplifying the best kind of effortless pedagogy. They inspire. Upon learning that Dorothy Macardle’s Uneasy Freehold (1941), for example, is one of their favorites, who can resist the urge to read it? Turn to any page and find a fascinating detail. For instance: Regina Maria Roche’s third novel, The Children of the Abbey (1796), which I had never heard of, “sold better than Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho and was a best-selling hit for Minerva Press.” Did you know that Margaret Campbell, who published her work as Marjorie Bowen, authored over 150 books? Or that Dion Fortune, a genuine believer in magic and the occult, who some argue helped lay the foundation for modern Wicca, during World War II “marshaled her occultist colleagues and like-minded magicians to create protections for Britain against German invasion, via group visualizations of spiritual guards positioned along the country’s coast”?

The book sparks questions, not always answered. When writing about Ann Radcliffe, Kröger & Anderson reveal: “She famously hated his [Matthew Lewis’s] novel The Monk (Joseph Bell, 1796).” Why? We are told that Pauline E. Hopkins’s Contending Forces: A Romance Illustrative of Negro Life North and South (1900) “also contained elements of the supernatural;” what are they? Did Hopkins influence Toni Morrison? And so on.

It must have been challenging to define this book’s limits, and to agree on its necessary omissions. I wish there had been some coverage of “modern” Gothic paperbacks. “There’s a strong argument that horror as it exists in the twenty-first century evolved from the Gothic novel,” submit the authors, a point with which I fully agree, and so it might have been instructive to spend a couple of pages on the faux Gothics that gained popularity around 1963 and flourished throughout the ’70s and into the early ’80s (both anticipating, and overlapping with, the “traditional” paperback boom covered extensively in Grady Hendrix’s Paperbacks from Hell [2017]). Prolific and popular writers in this admittedly niche subgenre included Florence Stevenson, Dorothy Daniels, Charlotte Hunt, and Jacqueline La Tourrette, among others. Of wider historical import, I think, writers like Gertrude Atherton, Olivia Howard Dunbar, and Georgia Wood Pangborn would have made for meritorious subjects (see Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock’s Scare Tactics: Supernatural Fiction by American Women [2008]). One should not expect a primer to be encyclopedic–though, thanks to its many chapter-ending suggestions for further reading, this one nearly is.

Most of my examples in this review are taken from the book’s early sections, simply because I found them so historically fascinating, but the latter material is equally top-notch. Perhaps my only quibble is that the final chapter failed to mention horror editor-par-excellence Ellen Datlow, whose prodigious, genre-molding labor deserves at least a paragraph of recognition in any type of summation like the one provided. Kröger & Anderson’s book eloquently proves “that women have been contributing to the genre since its inception,” and the thrill of the rediscoveries they have made available to us is perhaps only outshined by the hope of future contributions that will burn brighter still.

This review and more like it in the December 2019 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.