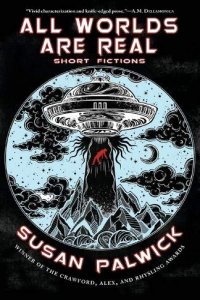

Paul Di Filippo Reviews All Worlds Are Real by Susan Palwick

All Worlds Are Real Era, Susan Palwick (Fairwood 978-1933846842, $17.99, 322pp, hardcover) November 2019

All Worlds Are Real Era, Susan Palwick (Fairwood 978-1933846842, $17.99, 322pp, hardcover) November 2019

With the publication of her new story collection, All Worlds Are Real, Susan Palwick charts her sixth book over the course of her 35 years of professional publication. Measured reductionistically by number of pages produced, she has not been extremely prolific. But when gauged by the quality of her prose and the allure and wisdom of her tales, she has piled up more literary credit than many a bestselling author of scads of trilogies. It is rare indeed that a story collection in this or any other genre can be characterized as graceful and full of grace; concise yet expansive; calm yet thrilling; topical yet timeless; and full of lighthearted gravitas. These streamlined stories all exhibit clean, strong and authentic narrative frames that are packed with powerful tropes brilliantly handled. You will emerge from immersion in this book feeling you have actually lived these lives.

Let’s have a gander at what awaits; all the stories are of recent vintage, with three being unique to this volume.

“Windows” is a seemingly contemporary slice-of-life scenario that portrays a melancholy mother riding a long-distance bus to visit her son in prison. But when we learn that her daughter, the sister, is embarked on a one-way mission on a generation starship, we are forced to question what constitutes freedom and faith, and whether prisons come in different shapes. In “The Shining Hills”, there’s a kind of fairy plague abroad in the world, a numinous phenomenon that lures sensitive people to some kind of transformative event. (See “Sanctuary” below for an allied riff.) Do those who heed this Pied Piper benefit or suffer, and what of those left behind?

“Ash” is a story that might have come from the pen of Kit Reed, a fine author with whom Palwick seems naturally allied. A woman whose house burns entirely down finds that a tree surviving on the property begins to offer certain resurrected treasures, culminating in possible horrors. The wonderfully titled “Cucumber Gravy” calls to my mind the best work of Clifford Simak. An eccentric loner named Welly, who survives by low-level dope-dealing, finds his house the target for enigmatic aliens.

There’s a Paul Park vibe to “Hhasalin”, specifically to Park’s great novel Celestis, which charts the fallout of human-alien interactions and rituals of dominance and conformity. The lead character, an alien named Lhosi, becomes at once an object of pity and a tower of strength, as she confronts the truth of what humans have done to her fallen culture. The literal Christian Rapture, or something closely akin, has already occurred before the story titled “Sanctuary” begins. This leaves us in media res with the Left Behind sinners as they scrabble to make a life from the shards of civilization. When you add in the weird paradigm-shift physics similar to those found in Jack Vance’s “The Men Return”, you get a heady trip.

The first previously unpublished offering is “City of Enemies”, which displaces the subject of postmodern terrorism to an alternate fantastical world where its lineaments can be more objectively discerned, through the life of Inru, a suicide bomber who survives. Can you beat the opening line of “Lucite”? “The Tenth Circle of Hell is a gift shop.” I thought not. A soul-souvenir from this weird place changes the life of a fellow named Andrew upon his return to the mortal sphere. A disreputable mutt named “Hodge” lends his cognomen to the title of the next piece, our second hitherto-unseen offering. He enters the life of Nellene, a mentally disturbed woman, and proves a comfort even when no longer alive. A good old-fashioned historical sea adventure occurs in “Homecoming”, as a group of youngsters encounter myriad challenges, including archetypical sirens. John Crowley’s famous tale “Snow” and its afterlife theme get a fitting companion in “Weather”, which manages vividly to convey the core conceit of talking to the dead even though that technology is totally offstage.

“Hideous Flowerpots” is a story that, I venture to say, Kelly Link would have been proud to write. An art gallery owner, full of blockages, neuroses and bad juju finds her life changed for the better by a peculiar women’s support group and their—get ready for it—magic tape measure. You might not imagine that Palwick could channel Thorne Smith, but she does so in “Remote Presence”, which finds a medical telepresence robot possessed by a ghost. I was also reminded of Heinlein’s atypical and whimsical “Our Fair City”. Is there a symmetry between Alcoholics Anonymous and Alien Abductions? You must read “Recoveries” to find out. Finally, the third just-debuting tale arrives in the form of “Wishbone”, which neatly circles back to the story “Windows” as it presents the memories of the last person aboard a slower-than-light starship who still recalls the planet of their origin.

As Jo Walton notes in her lucid introduction, Palwick specializes in asking “‘what if’ questions of the human heart.” All her speculative scenarios, however cleverly and intricately constructed, take a back seat to the psychological and emotional odyssey that each character undergoes in his or her search for how best to relate to others, and to oneself, and how to balance communal duties against individual needs. Whether it’s Welly, confined to his hermitage in order to be shepherd to the visiting aliens, or Lhosi, expending the last of her life force to honor her people, Palwick’s protagonists generally come down, however reluctantly at first, on the side of sacrifice and interconnectivity with even those opposed to them (see “City of Enemies” and “Sanctuary”).

All these beautifully limned journeys are conveyed in a trademark prose that is full of telling details calmly and crystal-clearly conveyed, details which also deliver insights into the protagonist. I’ll let the opening paragraph of “Ash” stand for the rest of the book.

Penny told herself that the fire had been a blessing, a cleansing: all that junk she’d meant to sort through and discard, all the books she knew she’d never read, the letters and Christmas cards she’d never reread. Oh, she wasn’t a hoarder; it hadn’t been as bad as that. But she’d had file drawers that had gone unpurged for twenty years, because she’d tried to clean them out and been stopped dead in her tracks by things no one else would ever want that were simply too precious to discard: the short story she’d written in French and illustrated in colored pencil in eighth grade, with her teacher’s ecstatic “A+! Merveilleuse!” in red marker; her long-dead mother’s birth certificate; files of papers holding ideas for essays and articles she’d never write now that she’d retired from the university. And suddenly, everything had to be kept.

She’d thrown out plenty of other stuff: teaching files, old magazines (even the ones she’d meant to read and never had), her seminar papers from grad school. She needed to do more, but felt paralyzed.

And so the fire was a blessing. It happened when she was on vacation, visiting a friend in Seattle, the cats—thank goodness—safely boarded at the vet’s. Some kind of short, the firefighters thought, wiring gone had in the walls, although Penny could have sworn she’d turned everything off. Maybe shorts could happen anyway. She didn’t know.

Any reader who’s even just a little bit tired of intergalactic warfare, endless heroic quests, and bloody abominations will revel in Palwick’s down-to-earth yet miraculous fables.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.