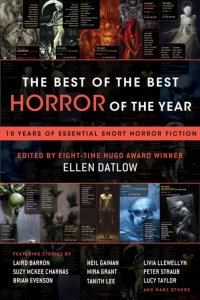

Paul Di Filippo Reviews The Best of the Best Horror of the Year, Edited by Ellen Datlow

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year, Ellen Datlow, ed. (Night Shade Books 978-1-59780-983-2, $17.99, 432pp, trade paperback) October 2018

In the hurly-burly of making literature—writing fiction, buying it, editing it, publishing it, selling it, promoting it, reviewing it—one’s focus is always on the immediate. Tasks to do, commitments, hopes and aspirations, victories and defeats, what’s new now, the latest thing. Faddish trends can intrude, and flavors of the month can go viral, then be swiftly forgotten. Perspective and judgment can be obscured or even lost.

In the hurly-burly of making literature—writing fiction, buying it, editing it, publishing it, selling it, promoting it, reviewing it—one’s focus is always on the immediate. Tasks to do, commitments, hopes and aspirations, victories and defeats, what’s new now, the latest thing. Faddish trends can intrude, and flavors of the month can go viral, then be swiftly forgotten. Perspective and judgment can be obscured or even lost.

But then, at annual intervals, the whirligig slows down enough for some retrospective looks at what mattered, the high points of the year. Peaks and valleys, survivors and wreckage, both stand out more clearly, once the publishing tsunami recedes for a moment of stillness. Then we get awards, critics’ lists and the best-of-the-year collections.

And of course, longer sweeps of time allow even greater clarity.

For almost four decades now (her entry in The Science Fiction Encyclopedia states, “She first became influential as fiction editor of Omni (1980-1995)…”), Ellen Datlow has been central to both the day-by-day headlong rush of genre publishing, and also the more contemplative assessments of what endures. Her various stints assembling annual best-of volumes has given her a deep sense of which stories stand the best chance of meriting the praises of posterity.

And so when we see that she has distilled the past ten years of her best-of selections into a best-of-the-best, we can immediately feel confident that we are in for a book’s worth of superlative stories. And indeed, this volume does not disappoint. It’s the kind of anthology you can hand to a friend who does not know the horror field—or even claims to dislike horror—and be sure that it will convert them into a passionate fan.

Does this table of contents form anything like a canon for the horror writings of the past decade? Well, a canon usually results from a mass consensus of opinion, and these selections are just the choices of one person. Still, it’s a not-inessential first step towards defining such a beast.

Let’s step through the two-dozen-plus tales to show what awaits the lucky reader, before making a few general observations.

In “Lowland Sea” Suzy McKee Charnas gives us a shattering apocalypse that echoes Poe, as she follows a woman named Miriam who takes a surprise lackey’s revenge on her elite “master.” A serial killer operating in the Mojave desert receives his due supernatural justice in “Wingless Beasts” by Lucy Taylor. One can feel the heat. Glen Hirshberg delves into the true eeriness of the aurora borealis in “The Nimble Men.” Another post-civilization wasteland, this time with mutants and ruthless survivors, is explored in “Little America” by Dan Chaon.

Could one improve on du Maurier’s “The Birds”? Only if you are Tanith Lee, imagining a “Black and White Sky.” She renders a catastrophe that is at once muted and horrid. Melting faces and other images of body horror populate “The Monster Makers” by Steve Rasnic Tem, which is remarkably dense and compact in its telling. The perennial trope of zombies, leavened with the rituals of the academic life, gets a fast and furious workout in Stephen Graham Jones’s “Chapter Six.” Resonating with the primo American Gothic stylings of Lucius Shepard, “In a Cavern, in a Canyon” finds Laird Barron charting the jinxed life of middle-aged Hortense and her appointment with the “help-me” beast.

HPL’s thoughts on the living malignity of the landscape find expansion in “Allochthon” by Livia Llewellyn, who charts the cycles of entropic recurrence afflicting a trapped woman. Stephen Gallagher vividly summons up the year of 1947 and the life of a country doctor on an isolated island in “Shepherds’ Business.” The tale runs like a James Herriot memoir until it explodes into grand guignol. The flash fiction from Neil Gaiman, “Down to a Sunless Sea,” evokes shudders effectively with the tale of a mourning mother. Almost like a Manly Wade Wellman folkloric piece, but with a more cosmopolitan narrator, “The Man from the Peak” by Adam Golaski invites the titular monster into a farewell party already fraught with tension and longings.

John Langan skillfully conflates a spy thriller and Hellboy-style shenanigans with “In Paris, In the Mouth of Kronos.” His two operatives banter, bicker, then face the unfaceable. “The Moraine” by Simon Bestwick is an old-school chiller about the creature that lurks beneath a misty mountainside. It has almost an SF flavor about it. “At the Riding School” finds Cody Goodfellow pulling out all the Robert Graves White Goddess stops on his account of the lewd doings at a peculiar girls’ academy. E. Michael Lewis considers the ghostly outcome of armed conflicts in “Cargo,” where a very limited setting—an airplane in flight—proves highly claustrophobic. Can zombies recover from their condition? That’s the question asked by Stephanie Crawford and Duane Swierczynski in “Tender as Teeth.” Their mordant humor mixes with real emotional payoffs.

Two gruesome (preventable?) deaths by a monster kick off “Wild Acre” by Nathan Ballingrud, who then meticulously charts survivor guilt and psychosis. Can arcane ancient rituals still exist in such an unlikely setting as a bingo parlor? Ramsey Campbell affirms so in “The Callers.” Tanner Falls is a town curiously isolated by Lovecraftian ceremonies, resulting in a feeling best characterized as “This Stagnant Breath of Change.” So Brian Hodge ruthlessly affirms. Reminiscent of Pat Murphy’s novel The Falling Woman, “Grave Goods” by Gemma Files concerns the terrors that can be dug up by unwitting archaeologists.

Riffing on the same existential malaise covered by Tom Disch in his famous “The Asian Shore,” Peter Straub charts the folie-a-deux psychosexual terrain inhabited by two lovers in “The Ballad of Ballard and Sandrine.” The military milieu harbors a demon who exults in battlefield carnage in “Majorlena” by Jane Jakeman. The narrator of Adam L. G. Nevill’s “The Days of Our Lives” might be the definition of passive-aggressive complicity as he participates in the depraved doings of a woman named Lois. If Stephen King rewrote Dr. Seuss’s If I Ran the Zoo, you’d end up with Mira Grant’s “You Can Stay All Day.” The flash fiction from Brian Evenson, “No Matter Which Way We Turned,” evokes body horror in spades. “Nesters” by Siobhan Carroll places familial monsters in a Depression-era setting with some of the feel of classic Richard Matheson. And to round out the selections, “Better You Believe” by Carole Johnstone stages its frigid horrors in the classic high-mountain zone of death.

Perhaps the first thing to mention is that Datlow could have chosen another completely different set of tales from thirty different writers and produced a volume nearly as strong. That’s just how chock-full of talent the genre is these days.

Next comes the observation that all these authors are superb at naturalism. They all prefer to stage their tales in settings that are either “mundane”—Laird Barron’s low-rent neighborhoods—or, if exotic—Carole Johnstone’s Himalayas—still well-chronicled and familiar. The fusion of the everyday with eruptions of the horrific and unnatural is a potent combo, of course, and the preferred mode these days. But conversely, this means there is less overt surrealism or out-of-this-world horror. No Kafkaesque castles, or even Aickmanesque oddities like a dollhouse manifesting huge in the middle of a forest. Maybe Straub comes closest to a kind of de Chirico effect. Certainly there’s no Clark Ashton Smith or something like HPL’s “In the Walls of Eryx.” This seems a lack to me.

Modern horror seems also to have finally achieved a harmony between Victorian over-subtlety and vagueness and splatterpunk in-your-face gore. These tales walk the tightrope between enigmas and explicitness. They also represent a fusion of topicality and timelessness, dealing with both eternal concerns of the human soul and spirit and hot-button issues.

In short, the contemporary horror field as Datlow’s selections represent it to us, has matured, shifted its focus a bit, and yet not entirely lost its roots to the soil of the past classics in which it is rooted. Perhaps a little more pulp outrageousness and a willingness to venture to stranger venues might be all one could ask for from the best of the best.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.