Liz Bourke Reviews Gunpowder Moon by David Pedreira

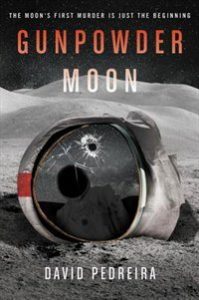

Gunpowder Moon, David Pedreira (Harper Voyager 978-0-06-2676085, $14.9, 304pp, tp). February 2018.

Gunpowder Moon, David Pedreira (Harper Voyager 978-0-06-2676085, $14.9, 304pp, tp). February 2018.

I began reading David Pedreira’s Gunpowder Moon, the debut novel of a former Florida journalist, with a fair degree of optimism. Its big idea – helium-3 mining on the moon – is fairly well discredited junk science (see Charles Stross, “Science-fictional shibboleths,” 4th December 2015) but this is science fiction. Junk science is practically traditional, and writers such as Ian McDonald have written fascinating thrillers (and subtly ironic interrogations of moondust libertarianism) around He3 mining and the wild lunar frontier. Reading Gunpowder Moon proved a disheartening experience.

Caden Dechert, a former military man, is the chief of a US mining operation on the moon. It’s 2072, and the environmental crisis that has destroyed Earth’s economy and upended global energy policy has been established fact for ten years. Despite this environmental crisis destabilising global power relations, the USA, China, Russia, and India are still global (and now lunar) powers. (The EU, with all of its member states, has apparently been wiped off the map.) The US and China have been ramping up their sabre-rattling, and the conflict may spill over onto the moon – though the moon has always been a demilitarised zone. When a bomb kills one of Dechert’s miners, it looks like the march towards war will become a sprint.

Dechert is a typical noble-but-cynical-haunted-veteran type. He believes in one thing: war shouldn’t come to space. So he sets out, against the wishes of his superiors, to find the truth. He wants to put out the fuse that’s burning towards a lunar explosion, but no one really gives a shit. Everyone either has their orders, wants to protect their status, is powerless to prevent the war, or wants it to happen. He finds a conspiracy – not very surprising – but can he tell anyone who cares in time to make a difference?

That’s Gunpowder Moon, a pedestrian and predictable quasi-military thriller occasionally enlivened by some luminous moon-descriptive prose. But if that were all it is, it would be scarcely disheartening. No, the disheartening things about it are the assumptions deeply embedded within its narrative. About who’s important. Who’s worth telling a story about.

In a novel with a cast of… well, in the double-digits of named characters, anyway, there are two named women. One is a military lieutenant who shows up late and has perhaps two lines of dialogue. The other may as well be the only civilian woman on the moon: Lane Briggs, introduced early on as The Girl (the only woman in Dechert’s team of seven or eight miners). The text can’t resist reminding us that she’s a girl and girls are different than men and men lust after them and men act differently around them, and directing a constant stream of low-grade sexual harassment in her direction. The text seems to believe this is humour, not harassment, but it made me think uncomfortable things about the reporting chains for sexual assault and the likelihood of coercive sexual encounters in an environment where your safety depends on the goodwill of the men around you. Briggs is omnicompetent, cool and collected – and Dechert, by virtue of his position as her boss, has access to information about her past sexual relationships – because apparently they all work for a company that spies on that sort of thing and puts it in the employee file, and this is normal and not a problem at all (and Dechert never considers that his boss knows all about his relationships, nor brings this information up with regard to the men he works with).

This is a novel in which, fifty years from now, after an environmental disaster that’s destroyed their economy – and most of the world’s – Americans are still shooting people in the Middle East, referring to “Hajiville,” and generally continuing their eternal Middle Eastern war, now in Lebanon. It’s a novel in which Dechert has a Chinese friend called Lin Tzu, who can trace his descent (apparently) from the famous Sun Tzu. Perhaps some marginally competent copyeditor will point out before the final published version (I read an advance copy) that the tzu in Sun Tzu is an honorific, and that Chinese names generally start with one’s surname, with the personal name coming second.

I have higher standards than this. Science fiction can be better than this. It doesn’t have to thoughtlessly reproduce today’s social dynamics, now with vacuum outside the windows. Gunpowder Moon is a story that has no ambition for the future: its science, its characterisation, and even its dystopian dabbling lack real imagination. There is a place, I suppose, for the mediocre. I’ve just been spoiled for it by the good.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, is out now from Aqueduct Press. Find her at her blog, her Patreon, or Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.

This review and more like it in the April 2018 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

Thank you for the telling review. I’ll remove it from my list of audiobooks to listen to. I’d make me cringe if I did hear it narrated.

I usually read what this reviewer has to say with interest, but this review seems misguided. In fact, I am willing to give the author a benefit of the doubt – perhaps, the Gunpowder Moon should be interpreted as a warning novel. BTW, this sub-genre was very in the former Eastern Europe.

However, I find another flaw – and I am talking here about the entire dystopean sub-genre. The unspoken underlying assumption in dystopia is that the humanity can not be better that its worst part – a kind of Lusser’s law for futurism. I refuse to read yet another novel about a future Earth taken over by greedy corporations; or about highly advanced space faring aliens that come to Earth to steal our oil/women/gold/platinum/etc. Or militarized futures or ultra-conservative super-right/left futures, or post-whatever survivalist-wet-dream futures, etc.

Where are the grand views of the future trans-human civilizations?

I give an example from the classics, I hope that it is familiar to everybody: Wells’es time traveler went to the future to find a predation dead-end world. In contrast, Olaf Stapledon wrote a future history where intelligence (not necessarily human!) again and again rises above its undoings. I find it more interesting to read about the birth of an artificial being and the grand vision of the trans-human civilization of Greg Egan, than about the a corporation that exploits (yet again!) the resources of the Moon or the nearby Alpha Cen planets or (fill in the blank).

All this said, I do realize that dystopas provide dramatic conflict, but I also think that this is a cheap way to create drama. Unfortunately, many writers don’t want to work hard or they simply lack an imagination and they again and again resort to the familiar dystopean tropes. I am willing to excuse the repetition of familiar ideas, but at least they have to be to-told in a new and interesting way.

Thanks for the review. I was thinking that the description sounded interesting, but based on the review, it sounds like I would end up really annoyed. I will pass, and go on to a different hard SF novel.