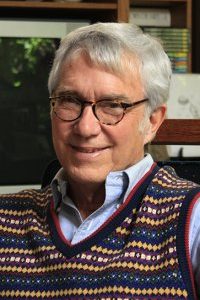

Karin Tidbeck: Language Matters

Karin Margareta Tidbeck was born April 6, 1977, in Stockholm, Sweden, and grew up in the suburbs. She briefly attended university before dropping out. She worked at various jobs, including in a bookshop, and just before she turned 30, enrolled in a three-year arts program. She attended the Clarion Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers Workshop in 2010.

Her debut collection Vem är Arvid Pekon? (2010) appeared in Sweden. First English-language collection Jagannath was published in 2012, including translated stories from Vem är Arvid Pekon? alongside newer material; it won the Crawford Award for best first fantasy, was a World Fantasy Award finalist, and made the Tiptree Award honor list. Debut novel Amatka was published in Sweden in 2012 and appeared in English in 2017.

Tidbeck lives in Malmö, Sweden, where she works as a freelance writer, creative writing instructor, and translator.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘My novel Amatka is about people colonizing a world that responds to language. Matter is literally controlled by language. It’s about what happens to a community when they try to survive in a world like this, what kind of order they build, how the situation controls their language, and what it does to their mindsets. It’s about revolting against that order. It’s about the power of names, the power of language, and also about how poetry can upset the order of things.”

*

‘‘The premise, to me, might not be science fiction at all. It may look like science fiction, but it might as well be portal fiction or weird fiction in a science fiction jumpsuit. But to be honest, I’m not too eager or bothered to categorize it as any genre. That’s up to the reader. I’m fine with them categorizing it as science fiction, or fantasy, or weird fiction, or surrealism.”

*

‘‘I don’t think about the reader when I write. I tell the story that needs to be told. I don’t think about how the reader is going to react. I basically tell the stories that go on in my head. It’s a very organic process. I’ll find a scene, or a word, or a sentence, and explore that – sort of walk around it, sniff it, trying to figure out how it works. That’s how most of my stories develop. I do a lot of automatic writing. I’ll just start writing nonsense. After a while something comes up – an image, a sentence, a scene, or the basic plot for a story. There’s only one instance where that didn’t happen, where I had a sentence pop up in my head unbidden, which was the beginning of a story called ‘Beatrice’. I was walking down the street and a voice whispered in my head that a doctor fell in love with an airship. I had to go home and figure out what that was all about.

‘‘I don’t write metaphors. Swedish mainstream readers really want to see my work as a metaphor, because that’s how they learned to read speculative fiction. It has to be a metaphor for something else. But I don’t write metaphors. I write ideas. What you see is what you get, pretty much. I wonder if that’s a way for readers to keep their dignity. They can say, ‘I’m reading this because it’s a metaphor,’ because they can’t say, ‘I’m reading this because it’s science fiction.’ ”

*

‘‘I worked at a science fiction bookstore in Stockholm, and I would read Locus during my lunch break. I read about Clarion at UC San Diego, and started fantasizing about going to Clarion, and about being published and seeing my books in the store. I decided to become better at English, and also took a creative writing course for one year. It was a mainstream writing course and they didn’t really understand speculative fiction, so they weren’t very encouraging. I abandoned that and took other day jobs and wrote some stuff on the side. I wrote a lot of characters and plot lines for various live-action roleplaying games. Then when I was 29, I realized that I had to make a serious attempt at becoming a writer. I moved to the south of Sweden, where I went to an arts college and studied creative writing for three years. They were very encouraging. I had one teacher who was a Lovecraft fan who helped me developed my skills.”

*

‘‘One of the most important reading experiences I had was with Neil Gaiman’s Sandman comics, which I started reading when I was 15. That was a formative experience, it really was. Him and Ursula K. Le Guin, obviously. I read Kafka when I was ten. I was the odd kid in the class. We were doing book presentations in the fourth grade, and I brought in Kafka’s The Metamorphosis. The other kids had no idea what that was. I didn’t read Borges a lot, because I thought he was too long-winded, and I had trouble parsing his sentences. I just didn’t get into his prose, but then I was reading Swedish translations of his work. I read a lot of Forteana, and also Robert Anton Wilson. I read a couple of books by Philip K. Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep and The Divine Invasion. I also devoured H.P. Lovecraft’s works. Lovecraft is an extremely problematic writer, but what I think I took away from him was the concept of madness and reality, the sensation that our reality is just a thin shell, and behind that shell, things move, things that we cannot understand, that we cannot conceive of. I read Solaris, but that’s the only Lem I read, and I can’t say he’s a huge influence – I read it pretty late. I think what might have had more influence on me was Tchaikovsky’s version of Solaris. Speaking of Tarkovsky, there’s also his adaptation of the Strugatsky brothers’ Stalker.”

*

‘‘I just finished another novel, which is with my agent right now, so I can’t really talk about it. It has a multiverse, so let’s just call it a weird dark fantasy novel. You could call it portal fantasy, or you could call it weird fiction. I think that, much like Amatka, it’s difficult to categorize. I will not cater to the audience. I write what’s in my head and then it’s up to the reader to categorize it. I don’t own the text anymore. It belongs to the reader. That goes partly back to me writing for LARPs, because what you do there is create the story or the character and hand it over to someone who does what they want with it, they improvise and make it their own. I’m used to the idea of creating something and giving it to someone else. It’s what I do in my fiction. Once I’ve create it, it doesn’t belong to me anymore. It’s graduated. It’s interesting when readers try to figure out what my motivations are, because, as far as I’m concerned, my motivations don’t matter anymore.’’