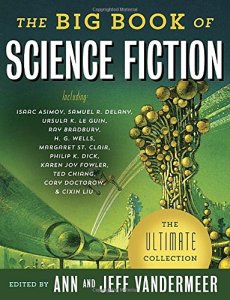

Faren Miller reviews The Big Book of Science Fiction

The Big Book of Science Fiction, Ann & Jeff VanderMeer, eds. (Vintage 978-1-101-91009-2, $25.00, 1,176pp, tp) July 2016.

In their Introduction to The Big Book of Science Fiction, editors Ann & Jeff VanderMeer note that they’re dealing with 20th-century fiction that ‘‘depicts the future, whether in a stylized or realistic manner’’ – emphasis theirs – and the breadth of the definition proves to be crucial. They link SF to the conte philosophique (thought experiment as fictional adventure), reevaluate pulp (‘‘never as hackneyed or traditional or gee-whiz as it liked to think it was’’), and trace a great flowering to the ’50s, where the lack of a ‘‘unifying mode or theme’’ allowed writers to ‘‘climb even farther up the walls of the world.’’ The arena continues to expand in the next decades: ‘‘While the New Wave and feminist science fiction were playing out largely in the Anglo world, the international scene was creating its own narrative.’’

In their Introduction to The Big Book of Science Fiction, editors Ann & Jeff VanderMeer note that they’re dealing with 20th-century fiction that ‘‘depicts the future, whether in a stylized or realistic manner’’ – emphasis theirs – and the breadth of the definition proves to be crucial. They link SF to the conte philosophique (thought experiment as fictional adventure), reevaluate pulp (‘‘never as hackneyed or traditional or gee-whiz as it liked to think it was’’), and trace a great flowering to the ’50s, where the lack of a ‘‘unifying mode or theme’’ allowed writers to ‘‘climb even farther up the walls of the world.’’ The arena continues to expand in the next decades: ‘‘While the New Wave and feminist science fiction were playing out largely in the Anglo world, the international scene was creating its own narrative.’’

Narratives also run through this anthology (just under the surface). Though presented in order of publication, these stories were chosen for continuing relevance and arranged to interplay like voices in a great conversation: shifting and offering new insights.

The key role of perspective appears immediately, as ‘‘The Star’’ by H.G. Wells moves from a major tragedy on Earth (cometary near-miss whose dire effect resembles the worst predictions for a warming climate in this century) to a Martian coda where ‘‘very different beings from men’’ see less change than expected – showing ‘‘how small the vastest of human catastrophes may seem, at a distance of a few million miles.’’

Long after the scientist in Alfred Jarry’s ‘‘Elements of Pataphysics’’ shrinks down to the size of a mite to explore a water drop, there’s an odd flicker of déjà vu in the water world of ‘‘Surface Tension’’ when James Blish uses ‘‘pantropy’’ to bioengineer miniature colonists from human cells, then follows generations to the cultural apex of something resembling space flight (writ small in this tale from the early ’50s, its true purpose almost forgotten).

Theodore Sturgeon’s ‘‘The Man Who Lost the Sea’’ (1959) splits a doomed explorer into the trapped body of ‘‘the sick man,’’ and a mind in turmoil: ‘‘Say you’re a kid, and one dark night you’re running…’’ back toward Earthly oceans. When the parts reunite (scrabbled together a few million miles from home), the joy is bittersweet. In ‘‘The Astronaut’’, a Soviet-era work retranslated here by Jack Womack, Valentina Zhuravlyova calls the science behind such episodes Astropsychiatry, as a ship doctor does research in an Archive of Space Travel and learns about the captain of an ancient expedition to Barnard’s Star.

Once again the VanderMeers take us (‘‘onward, ever onward!’’, as that captain cries): from his choice on an alien planet to events on another strange world in Ursula K. Le Guin’s ‘‘Vaster Than Empires and More Slow’’. Where Zhuravlyova notes that the long tedium of spaceflight calls for candidates with ‘‘hobbies’’ to keep them sane, Le Guin starts by forthrightly declaring all starship explorers mad, but each probes deep enough into a crew member to show obsession that saves an imperiled mission.

I’ll end these ‘‘dialogs,’’ sampled from the abundance in The Big Book of Science Fiction, with Michael Bishop’s ‘‘The House of Compassionate Sharers’’ and Greg Bear’s ‘‘Blood Music’’. Both explore the madness when body meets machine: Bishop with a droid counterpart to a picture conceived by Oscar Wilde, Bear in a devious feat of bioengineering where every cell develops a mind (and music) of its own.