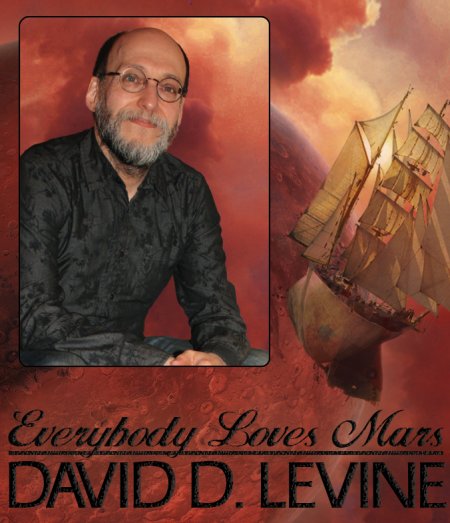

David D. Levine: Everybody Loves Mars

David Daniel Levine was born February 21, 1961 in Minneapolis MN. He grew up in Milwaukee WI, attended college in St. Louis MO, and then relocated to Portland OR, where he’s lived ever since.

Levine’s first publication of genre interest was story ‘‘1992: The Worldcon that Wasn’t’’ (1996), but he began publishing regularly with ‘‘Wind from a Dying Star’’ (2001), and has produced more than 50 stories so far, including James White Award winner ‘‘Nucleon’’ (2001), Hugo and Sturgeon Award finalist ‘‘The Tale of the Golden Eagle’’ (2003), Hugo Award winner ‘‘Tk’tk’tk’’ (2005), Nebula Award finalist ‘‘Titanium Mike Saves the Day’’ (2007), and Sturgeon and Nebula Award finalist ‘‘Damage’’ (2015). Some of his short fiction was collected in Endeavour Award winner Space Magic (2008). Levine was a finalist for the Campbell Award for Best New Writer in 2003 and 2004. He co-edits fanzine Bento with his wife, Kate Yule, and has served as convention chair for Potlatch.

His debut novel Arabella of Mars, first in a science fantasy series set in an alternate Regency era, appeared in 2016. Mars is an ongoing interest: in 2010 he spent two weeks living in the simulated Mars Desert Research Station in Utah.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘I’m happy in traditional publishing, though a lot of people say, ‘Oh, don’t do that to yourself, don’t saddle yourself with an agent, don’t do the traditional publishing thing – you would make so much more money and be so much happier with self-publishing.’ There’s no one offering advice on the question of traditional versus self-publishing who doesn’t have a dog in the fight. There’s nobody who can give you an unbiased opinion on which you should do. I am a traditional publishing partisan, but what I tell people is, you have to define your victory conditions. Your victory condition will control how you play. Do you want to make the most money? Do you want to have the most readers? Do you not care about money or readers, but want to be really well reviewed? Is having your paper book on the shelves of brick-and-mortar bookstores something that is important to you? Is being able to control your career important to you? There are all sorts of things that will determine whether you consider yourself to be successful. I don’t think these desires are subject to conscious control. You have to look inside yourself and decide, what is really important to me? They may change over time.”

…

‘‘Arabella is the fourth novel I wrote, and the first novel I sold. Novel number three is a hard SF YA set on Mars – that one definitely came out of my simulated Mars experience in Utah. Just about the time I was finishing that one up, I was shopping my second novel, and looking for a new agent. The responses I was getting from agents as well as editors was, ‘Science fiction just isn’t selling.’ I was getting this from the editors of science fiction houses! So here I was with a completed hard SF manuscript, and I said, ‘I don’t need the heartbreak.’ So I set it aside. Nobody has ever seen it, and it’s never been critiqued. I have no idea if it’s any good. Then I started working on something that would be science fictional enough satisfy me, but in a more fantastical mode – something I thought would be more salable. That was Arabella, and it seems to have worked.”

…

‘‘My primary influence for Arabella was Patrick O’Brian, though his books are more Napoleonic than Regency. Patrick O’Brian was described as what the men were off doing during Jane Austen, and I’m more strongly influenced by O’Brian than Austen. Arabella is an O’Brian, Horatio Hornblower kind of a thing, more than a Jane Austen thing. But you can’t escape the orbit of Jane Austen, especially after the trailblazing work of Mary Robinette Kowal, who has been a very helpful advisor to me. There’s a lot of information available about the Regency, especially for romance writers. There’s no end of research sources for me to get the details right, but getting the sailing tech right is much easier for me than getting the relationships and the societal mores right. I do need help on making sure that the other characters are not too 21st century in their worldviews. Science fiction readers really enjoy Patrick O’Brian. Apart from the fact that it’s well written and funny, it’s a viewpoint into a different universe. It’s painstakingly researched.”

…

‘‘I read an essay in a fanzine years ago called ‘The Science Fiction Archipelago’, and I’ve never been able to track it down since. It was predicated on the idea that science fiction grew out of a tradition of sea stories that started in the 1700s and 1800s. Everything about the kind of default science fiction universe is based on the sea stories of the 1700s. The idea that you can travel from one planet to another in a matter of weeks or months rather than days or decades. The fact that the captain of the starship is the one who is in charge, that there is no effective communication between the captains and their bosses back home, the relationships of people within the ship, the relationships of the people on the ship to the places they arrive, the idea that each island has a single culture – a single climate, a single religion, a single language – all of these science-fiction tropes come directly from the sailing mechanics and realities of 1700. There is a literary tradition – you can actually see the connection starting with Robinson Crusoe and the Swiss Family Robinson, and growing through the sea stories that were popular literature in the 1800s and 1900s, leading up into the pulps of the ‘30s and the science fiction today. There is both a literary and technological connection between sea stories and science fiction stories.”

…

‘‘First novels can be so much better sometimes than what comes later. You put your focus on other things. I mean, look at The Time Machine. That was Wells’s first novel, and it’s still his best known and best beloved. I am still pushing myself. With Arabella book two, the thing I’m working on is an ensemble cast, because everything I’ve written so far has had very small casts, basically one protagonist, and I’m trying to give her a team. The individuals have to be people on their own, and have interactions with each other. It’s new and difficult for me. In book three, there’s gonna be a lot more politics. Literal politics as well as interpersonal politics. I’m definitely trying to keep stretching.’’

Read the complete interview in the August 2016 issue of Locus Magazine. Interview design by Francesca Myman.