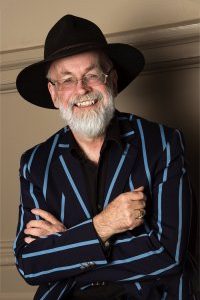

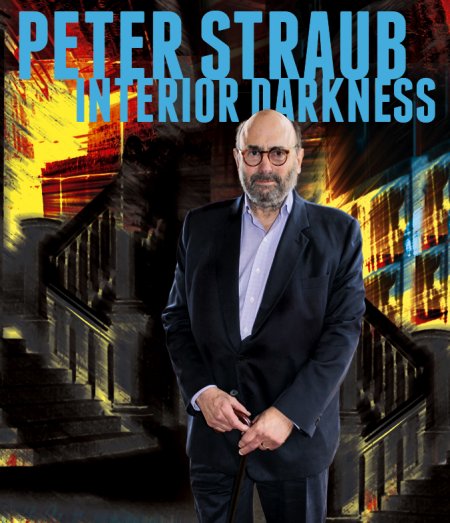

Peter Straub: Interior Darkness

Peter Francis Straub was born March 2, 1943 in Milwaukee WI. He earned a BA in English from the University of Wisconsin in 1965, an MA from Columbia University in 1966, then returned to Wisconsin to teach English at his former prep school for three years. In 1969 he moved to Ireland and began work on a PhD at University College in Dublin, but did not finish. He published two books of poetry in 1972, Ishmael and Open Air, and his first mainstream novel, Marriages, in 1973. At the suggestion of his agent, Straub decided to try ‘‘gothic fiction’’: first horror novel Julia appeared in 1975, and was later filmed as The Haunting of Julia. If You Could See Me Now (1977) followed, but his breakout novel was the bestselling Ghost Story (1979), later a film. His next supernatural novels were Shadowland (1980) and British Fantasy Award winner Floating Dragon (1983), followed by a few linked works that were mostly non-supernatural: novella Blue Rose (1985) and World Fantasy Award winner Koko (1988), Mystery (1990), and Stoker winner The Throat (1993). The Hellfire Club (1997) was a thriller, and Stoker winner Mr. X (1999) was a return to the supernatural. lost boy lost girl (2003) won a Stoker and a World Fantasy Award, and sequel In the Night Room (2004) won a Stoker. A Dark Matter (2010) won a Stoker, and novella A Special Place (2010) concerns some of the same characters. Straub collaborated with Stephen King on The Talisman (1984) and sequel Black House (2001).

His short fiction has been collected in Houses Without Doors (1990), Stoker winner Magic Terror (1997), 5 Stories (2007), The Juniper Tree and Other Stories (2010), and retrospective Interior Darkness (2016). Notable stories include World Fantasy Award-winning novella ‘‘The Ghost Village’’ (1992), Stoker and International Horror Guild Award winner ‘‘Mr. Clubb and Mr. Cuff’’ (1998), and Stoker winner ‘‘The Ballad of Ballard and Sandrine’’ (2011). Some of his non-fiction was collected in Sides (2006).

He edited HWA anthology Peter Straub’s Ghosts (1995), Conjunctions 39: The New Wave Fabulists (2002), the Library of America volume H.P. Lovecraft: Tales (2005), Poe’s Children (2008), and two volumes of American Fantastic Tales for the Library of America; the latter won a World Fantasy Award. His work is discussed in At the Foot of the Story Tree by Bill Sheehan (2000). An occasional actor, he appeared on a few episodes of soap opera One Life to Live from 2006-2009.

Straub was named a World Horror Grandmaster in 1997, won a Stoker award for life achievement in 2006, was named an International Horror Guild living legend in 2008, and received a life achievement World Fantasy Award in 2010. He married Susan Bitker in 1966; they have two children (including writer Emma Straub) and live in New York.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘It had been an unusually long time since I’d published a book, and I thought I had better do one just to remind people I was still breathing. It also occurred to me that, at my age and stage, a ‘Collected Stories’ made sense. I proposed the idea to my agent, who instantly pointed out that a collected stories would be way too much book. He said, ‘I think you should do a Selected Stories.’ I thought that was every bit as good, especially when I looked at how much I had and how quickly those pages added up. My problem being that very often when I intend to write a story, it takes on some of the ambitions of a novel, and pretty soon I am describing the characters’ grandparents, the house they moved into before they moved into the house they lived in now, what their younger brothers are doing, and what goes through their minds on the way to the grocery store. In other words, I novelize by instinct. Or by reflex, which is no wonder, because I’ve been novelizing, day after bloody day, for most of my adult life.

‘‘It’s a funny instinct to have. For one thing, it means I have trouble writing short stories. I’ve had this problem, this limitation, most of my writing life. Take a look: I’ve almost never written any! To be painfully truthful, it’s even been a long time since I was in the habit of reading them. I’m the reverse of those brilliant students who come out of MFA programs after having written maybe a couple of dozen short stories. I did write one with my daughter, Emma, for a recent anthology based on figures from mythology. It’s called Orpheus XO, and it was edited by Kate Bernheimer. She did a great job. Emma and I took what I thought was something like the easy way out and wrote a story based on Demeter. Why I thought that was going to be easy I can now no longer quite reconstruct. Emma had graduated from the glorious short story factory at the University of Wisconsin, where she’d had the immense good fortune of working closely with Lorrie Moore, one of our great writers. Since earning her MFA, Emma had been doing really well, in fact, given the shapes and conditions of most young writers’ lives, spectacularly well. We were going to swap our terrific little story back and forth and proceed at the rate of six pages apiece at a time. This was, let me say, Emma’s scheme. So she wrote the first six pages, hey presto, and sent them to me. At this point, I should probably confess that I see all such programs as suggestions, the same way I take almost everything said to me by doctors. Therefore, I took 10 days and sent back 12 pages. Emma groaned, a little. We kept repeating, and I kept adding in new characters, adding new neighborhoods to the little town where the father lived in the Hell parts of the story, which turned out way better than the other parts. Emma’s groans grew louder and more heartfelt. Finally she said to my wife, ‘Dad doesn’t know how to write a short story. I have an MFA, and I know how to write a damn short story.’ Our so-called short story wound up being about 50 pages long, which I see as a very nice length. Ideally, probably, it would be 90 pages long, which would have given us plenty of room for all the cool stuff I wanted to insert. One day, if Emma and I are lucky enough to last this long, we shall collaborate and turn our lovely, 50-page ‘Lost Lake’ into the novel I wanted it to be all along.

‘‘In a short story, you’re writing about something that changes a person’s character, or changes a person’s mind, or brings about some sort of insight, a revelation. Now, the minute I utter a stupid dictum like that, I realize everybody and his brother is going to tell me the ways in which I’m wrong, but the point is that you don’t have much room in a story. The short stories I have written, most of which are collected in this book Interior Darkness, are a little odd and tend not to follow the game plan I just described Usually, I’m not usually trying to write ‘a story.’ I’m doing something else that seems interesting and maybe even more compelling to me.”

…

‘‘My ideas about narrative have certainly changed with time, and my whole stance toward it has changed, as would have to happen in any long engagement with a subject. I don’t want to write the same kind of books I did when I started. Really, I can’t. I like reading novels that go from the beginning to the end. I like reading novels that don’t break the frame. I like novels that have endings one cannot anticipate, novels with jolting revelations. I like crime stories. I like Victorian novels. Conventional fiction strikes me as one of the most beautiful things made by man. Generally speaking, novels engage our sense of history, our imaginations, our moral sense. I have thought since I was 16 that there’s something very beautiful when you open a book and your eyes fall on the page and you read something like, ‘At 4:15 that afternoon the Countess of P–– emerged through the palace door and remarked upon the unusual strength of the sunlight.’ Anything like that. ‘When George Withers fell down on the sidewalk, all of his loose change fell out of his pocket.’ ‘As Hector Feelgood held the reins of the horses, the steam from their nostrils washed over his hands.’ Anything like that awakens a little bit of the world and delivers it to you like a loaf of fresh bread. It’s stunning. The whole fictional enterprise strikes me as very beautiful. I used to take it way more for granted than I can do now.”

…

‘‘Lovecraft and the Gothic novels are in my DNA for sure. It’s almost like they’re a couple of guys who got in on tourist visas and outstayed their welcome, camped out and got jobs as hotel clerks and in laundries, and just never went home. The reason they’re there at all has to do with Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural, one of the sacred books of my late childhood, which I toted around wherever I went. One summer, I took it to Boy Scout camp. I read Arthur Machen, I read Oliver Onions, and I read ‘The Dunwich Horror’, which has been my favorite Lovecraft story ever since, because I didn’t understand it when I first read it. I didn’t understand the resistance given to me by the language. I loved that it was so ornate. I loved that it resisted digestion. That was true of all those stories, the early stories. All this stuff is glamorous and ghastly, and completely exciting to the right 12-year-old boy.

‘‘One of the things that excited me was the unprecedented use of language. I’d never read stories that seemed directed at me yet that were written in a demanding, artifice-laden way. Machen’s ‘The Great God Pan’ was probably my favorite. I loved that story. I didn’t quite understand it, but I loved it. What I didn’t understand was concealed from me, deliberately, by the way it was written. Ever since, I have really liked narrative that’s chopped up and delivered in fragments. ‘The Great God Pan’ is probably the first significant story I read that was written in that way. It strikes me now as modernist. I don’t believe Machen was a modernist, but the narrative method was really interesting. Back then, I would’ve said, ‘The way this is written is really cool.’ I liked the slight layer of difficulty the fragmentation of narrative presented. I also like the idea of this mysterious woman Helen Vaughan and the terror that strikes the overconfident, blandly superior scientists who are investigating her case. It struck me even then that the sublime was probably too much to handle. Every angel is terrifying. I read Rilke many years later, but I think that is something I always knew, for reasons of my own.”

…

‘‘I look forward to working again – it’s so satisfying to work, to enjoy the act of writing. I love the act of making things up. I like creating things. It means an immense amount to me. In fact, sad to say, that’s the center of my being. All this time when I haven’t been able to do that, I have been separated from the center of my being, and in pure denial I have chosen not to think about that. I watch a lot of TV, because I don’t drink – there isn’t any alcohol involved and there are certainly no other toxic substances in the picture. It’s just a kind of mild boredom and a sense of working my way through a not very interesting day. There is none of the sense of the supercharged satisfaction, none of the inner glow, that comes from having worked well. I hope I can get back to that. I don’t see any reason why I can’t. I have a new office in our new apartment – it’s a pretty room, it has my old desk, I have floor to ceiling bookshelves, I have library ladders for the first time ever, and it’s cool. The only thing missing is the sound system, which is like a life-support system for me, and a good one is just about to be installed. The whole room is going to be filled up with books and music. Before we moved in, I went into the room and told it, ‘I’m going to fill you up. You don’t know it yet, but we’re going to have fun. You’re going to see things you’ve never seen before.’ Thereby proving, I guess, that I’m totally out of my mind. I’ve very much been looking forward to getting back to work.”

Read the complete interview in the July 2016 issue of Locus Magazine. Interview design by Francesca Myman. Photo by Liza Groen Trombi.