Faren Miller reviews Lian Hearn

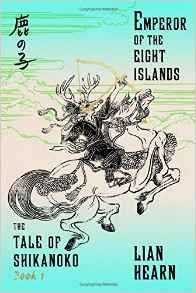

Emperor of the Eight Islands, Lian Hearn (Hachette Australia 978-0733635137, A$29.99, 448pp, tp) March 2016. (Farrar, Straus & Giroux 978-0-374-53631-2, $15.99, 252pp, tp) May 2016.

Emperor of the Eight Islands, first of four volumes in Lian Hearn’s ‘‘The Tale of Shikanoko’’ (all scheduled for this year), is a fantasy set in medieval Japan and inspired by some of its ‘‘warrior tales.’’ It draws on the pseudonymous author’s fascination with the country and culture, which led her to study them, and live there for a time. As the publisher informs us, she was ‘‘born in England, educated at Oxford,’’ and now lives in Australia.

Emperor of the Eight Islands, first of four volumes in Lian Hearn’s ‘‘The Tale of Shikanoko’’ (all scheduled for this year), is a fantasy set in medieval Japan and inspired by some of its ‘‘warrior tales.’’ It draws on the pseudonymous author’s fascination with the country and culture, which led her to study them, and live there for a time. As the publisher informs us, she was ‘‘born in England, educated at Oxford,’’ and now lives in Australia.

Despite its place in a tetralogy, extensive list of characters, elaborate map, and mixture of the historic with the supernatural, Emperor bears little resemblance to most epic fantasies set in medieval Europe. When he first appears as a seven-year-old named Kazumaru, the hero is hiding in the long grass on one of his father’s hunting trips. His horse has wandered off, and a flock of demonic creatures – ‘‘strange-looking beings, with wings and beaks and talons like birds, but wearing clothes of a sort, red jackets, blue leggings’’ – is flying past. Soon we learn these tengu (mountain goblins) have killed the rash lord who was his father, leaving the boy traumatized: ‘‘They saw me, he thought. They know me.’’

In the rest of this brief chapter, Hearn sketches out a youth where Kazumaru is raised by a cruel uncle, but manages to survive, and develops a passion for archery: ‘‘At twelve, he suddenly grew tall, and soon after could string and draw a bow like a grown man.’’ The next chapter deals with crucial events that transform Kazumaru into Shikanoko (‘‘the deer’s child’’), beginning with another hunting expedition where his uncle pursues a famous stag. A fall, a death, a passing spirit, and a dreamlike journey trailing uncanny guides bring him to the hut of a mountain sorcerer, its roof ‘‘thatched with bones, its walls covered with skins.’’ Here the sorcerer, with help from a mysterious woman, creates a mask that infuses him with ‘‘the strength of the stag and all the ancient wisdom of the forest’’ – changing his name forever.

New plotlines, settings, and viewpoint characters start to appear in the following chapters, alternating with accounts of Shikanoko’s increasingly complex life, which includes a stint with bandits and service to Lady Tora (who introduced Shika to his own sexuality with the rituals of the mask that she helped make). Viewed as a whole, it’s a fascinating blend of politics, priests, and monsters – some of them interacting in one man’s towering ambitions.

Unlike heroes who swiftly rise to power in their own kingdoms, Shikanoko isn’t the Emperor of this book’s title. While others struggle for that position, he hones various skills and absorbs unconventional magics that range from the woodland to a scholar’s languages and lore. The focus shifts to other characters (just as compelling, though some of them have little contact with him through most of the book), during a time of great change where a new form of warfare develops and the fate of a nation hangs in the balance. Still, this is Shika’s ‘‘Tale’’ in its early stages, and Hearn’s lead character gripped my attention from the start – leaving me eager to see how it plays out in the next books.